Electronics/Print Version

| This is the print version of Electronics You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Electronics

Aim

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

The aim of this textbook is to explain the design and function of electronic circuits and components. The text covers electronic circuit components, DC analysis, and AC analysis.

It should be useful to beginner hobbyists as well as beginner engineering students, teaching both theory and practical applications.

It should be thought of as a companion project to the Wikipedia articles about electronics. While Wikipedia covers many details about the technology used in electronics components and related fields, the Electronics Wikibook covers a lot of the "how-to" aspects that aren't covered in an encyclopedia. The book will focus on how to use the components to build useful circuits.

Prereq

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Prerequisite Topics

edit![]() Most important / Required knowledge

Most important / Required knowledge

![]() Moderately Important / Aids in comprehension

Moderately Important / Aids in comprehension

![]() Slightly Important / Related or helpful

Slightly Important / Related or helpful

Other Useful Topics

Preface

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Importance of Electronics

editElectronics is the study and use of devices that control the flow of electrons (or other charged particles). These devices can be used to process information or perform tasks using electromagnetic power.

Electronic circuits can be found in numerous household products, including such items as telephones, computers, and CD players. Electronic devices have also allowed greatly increased precision in scientific measurements.

Interest in the field of electronics increased around 1900 and the advent of radio. Interest reached an all-time high in the 1940s, 50s, 60s, with the invention of transistor radios, the launch of Sputnik, and the science and math educational push to win the space race. Interest in electronics as a hobby in the 1970s led to the advent of the personal computer (PC).

Electronics have since seen a decline in hobbyist interest. Electronics is now generally studied as part of a college-level program in electrical engineering.

This book is an attempt at reviving the hobbyist mentality that made electronics so big in the first place, by making electronics concepts more accessible and giving practical knowledge, as well as providing technical information for the student.

Charge and Coulomb's Law

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Two atoms are walking down the street. The first atom says to the second atom "I think I lost an electron!" The second says "Are you sure?" To which the first states "I'm positive!"

Basic Understanding

edit- Conductors

- Materials which contain movable charges that can flow with minimal resistance.

- Insulators

- Materials with few or no movable charges, or with charges which flow with extremely high resistance.

- Semiconductors

- Materials whose behavior ranges between that of a conductor and that of an insulator under different conditions. Their conducting behavior may be heavily dependent on temperature. They are useful because we are able to change their conducting behavior to be dependent on many other factors.

- The Atom

- An atom contains a positively charged nucleus and one or more negatively charged electrons. The atom exists in three states: neutral, positively charged, and negatively charged. A neutral atom has the same number of electrons and protons, a positively charged atom has more protons than electrons and a negatively charged atom has more electrons than protons.

- (+) and (-) Ions

- An ion is an atom that has an unequal number of electrons and protons. Ions are formed when a neutral atom gains or loses electrons during a chemical reaction. In a battery, the positive side has + ions, means there are fewer electrons than protons, giving it an overall positive charge, and -ve side, more electrons than protons, giving it an overall negative charge. +ve and -ve charge will attract each other, and it is the use of such an attractive force that allows the battery to do work.

Note: Electric current is not the same as electron flow as is widely mistaken. Firstly, the total current has the opposite direction compared to electron flow. This is a lucky "mistake" on our forefathers' part to put it this way. It is also because of this lucky legacy that we are reminded that electricity can flow in materials other than metals alone. For example, in water, it is not electrons that flow, it is ions, and the +ve ions and -ve ions flow in opposite directions, contributing half of the total current each.

Balance of Charge

editAtoms, the smallest particles of matter that retain the properties of the matter, are made of protons, electrons, and neutrons. Protons have a positive charge, Electrons have a negative charge that cancels the proton's positive charge. Neutrons are particles that are similar to a proton but have a neutral charge. There are no differences between positive and negative charges except that particles with the same charge repel each other and particles with opposite charges attract each other. If a solitary positive proton and negative electron are placed near each other they will come together to form a hydrogen atom. This repulsion and attraction (force between stationary charged particles) is known as the Electrostatic Force and extends theoretically to infinity, but is diluted as the distance between particles increases.

When an atom has one or more missing electrons it is left with a positive charge, and when an atom has at least one extra electron it has a negative charge. Having a positive or a negative charge makes an atom an ion. Atoms only gain and lose protons and neutrons through fusion, fission, and radioactive decay. Although atoms are made of many particles and objects are made of many atoms, they behave similarly to charged particles in terms of how they repel and attract.

In an atom the protons and neutrons combine to form a tightly bound nucleus. This nucleus is surrounded by a vast cloud of electrons circling it at a distance but held near the protons by electromagnetic attraction (the electrostatic force discussed earlier). The cloud exists as a series of overlapping shells / bands in which the inner valence bands are filled with electrons and are tightly bound to the atom. The outer conduction bands contain no electrons except those that have accelerated to the conduction bands by gaining energy. With enough energy an electron will escape an atom (compare with the escape velocity of a space rocket). When an electron in the conduction band decelerates and falls to another conduction band or the valence band a photon is emitted. This is known as the photoelectric effect.

A laser is formed when electrons travel back and forth between conduction bands emitting synchronized photons.

- When the conduction and valence bands overlap, the atom is a conductor and allows for the free movement of electrons. Conductors are metals and can be thought of as a bunch of atomic nuclei surrounded by a churning "sea of electrons".

- When there is a large energy level gap between the conduction and valence bands, the atom is an insulator; it traps electrons. Many insulators are non-metals and are good at blocking the flow of electrons.

- When there is a small energy level gap between the conduction and valence bands, the atom is a semiconductor. Semiconductors behave like conductors and insulators, and work using the conduction and valence bands. The electrons in the outer valence band are known as holes. They behave like positive charges because of how they flow. In semiconductors electrons collide with the material and their progress is halted. This makes the electrons have an effective mass that is less than their normal mass. In some semiconductors holes have a larger effective mass than the conduction electrons.

Electronic devices are based on the idea of exploiting the differences between conductors, insulators, and semiconductors but also exploit known physical phenomena such as electromagnetism and phosphorescence.

Conductors

editIn a metal the electrons of an object are free to move from atom to atom. Due to their mutual repulsion (calculable via Coulomb's Law ), the valence electrons are forced from the centre of the object and spread out evenly across its surface in order to be as far apart as possible. This cavity of empty space is known as a Faraday Cage and stops electromagnetic radiation, such as charge, radio waves, and EMPs (Electro-Magnetic Pulses) from entering and leaving the object. If there are holes in the Faraday Cage then radiation can pass.

One of the interesting things to do with conductors is demonstrate the transfer of charge between metal spheres. Start by taking two identical and uncharged metal spheres which are each suspended by insulators (such as a pieces of string). The first step involves putting sphere 1 next to but not touching sphere 2. This causes all the electrons in sphere 2 to travel away from sphere 1 to the far end of sphere 2. So sphere 2 now has a negative end filled with electrons and a positive end lacking electrons. Next sphere 2 is grounded by contact with a conductor connected with the earth and the earth takes its electrons leaving sphere 2 with a positive charge. The positive charge (absence of electrons) spreads evenly across the surface due to its lack of electrons. If suspended by strings, the relatively negatively charged sphere 1 will attract the relatively positively charged sphere 2.

Insulators

editIn an insulator the charges of a material are stuck and cannot flow. This allows an imbalance of charge to build up on the surface of the object by way of the triboelectric effect. The triboelectric effect (rubbing electricity effect) involves the exchange of electrons when two different insulators such as glass, hard rubber, amber, or even the seat of one's trousers, come into contact. The polarity and strength of the charges produced differ according to the material composition and its surface smoothness. For example, glass rubbed with silk will build up a charge, as will hard rubber rubbed with fur. The effect is greatly enhanced by rubbing materials together.

- Van de Graaff Generator: A charge pump (pump for electrons) that generates static electricity. In a Van de Graaff generator, a conveyor belt uses rubbing to pick up electrons, which are then deposited on metal brushes. The end result is a charge difference.

Because the material being rubbed is now charged, contact with an uncharged object or an object with the opposite charge may cause a discharge of the built-up static electricity by way of a spark. A person simply walking across a carpet may build up enough charge to cause a spark to travel over a centimetre. The spark is powerful enough to attract dust particles to cloth, destroy electrical equipment, ignite gas fumes, and create lightning. In extreme cases the spark can destroy factories that deal with gunpowder and explosives. The best way to remove static electricity is by discharging it through grounding. Humid air will also slowly discharge static electricity. This is one reason cells and capacitors lose charge over time.

Note: The concept of an insulator changes depending on the applied voltage. Air looks like an insulator when a low voltage is applied. But it breaks down as an insulator, becomes ionised, at about ten kilovolts per centimetre. A person could put their shoe across the terminals of a car battery and it would look like an insulator. But putting a shoe across a ten kilovolt powerline will cause a short.

Quantity of Charge

editProtons and electrons have opposite but equal charge. Because in almost all cases, the charge on protons or electrons is the smallest amount of charge commonly discussed, the quantity of charge of one proton is considered one positive elementary charge and the charge of one electron is one negative elementary charge. Because atoms and such particles are so small, and charge in amounts of multi-trillions of elementary charges are usually discussed, a much larger unit of charge is typically used. The coulomb is a unit of charge, which can be expressed as a positive or negative number, which is equal to approximately 6.2415×1018 elementary charges. Accordingly, an elementary charge is equal to approximately 1.602×10-19 coulombs. The commonly used abbreviation for the coulomb is a capital C. The SI definition of a coulomb is the quantity of charge which passes a point over a period of 1 second ( s ) when a current of 1 ampere (A) flows past that point, i.e., C = A·s or A = C/s. You may find it helpful during later lessons to retain this picture in your mind (even though you may not recall the exact number). An ampere is one of the fundamental units in physics from which various other units are defined, such as the coulomb.

Force between Charges: Coulomb's Law

editThe repulsive or attractive electrostatic force between charges decreases as the charges are located further from each other by the square of the distance between them. An equation called Coulomb's law determines the electrostatic force between two charged objects. The following picture shows a charge q at a certain point with another charge Q at a distance of r away from it. The presence of Q causes an electrostatic force to be exerted on q.

The magnitude of the electrostatic force F, on a charge q, due to another charge Q, equals Coulomb's constant multiplied by the product of the two charges (in coulombs) divided by the square of the distance r, between the charges q and Q. Here a capital Q and small q are scalar quantities used for symbolizing the two charges, but other symbols such as q1 and q2 have been used in other sources. These symbols for charge were used for consistency with the electric field article in Wikipedia and are consistent with the Reference below.

F = magnitude of electrostatic force on charge q due to another charge Q

r = distance (magnitude quantity in above equation) between q and Q

k = Coulomb's constant = 8.9875×109 N·m2/C2 in free space

The value of Coulomb's constant given here is such that the preceding Coulomb's Law equation will work if both q and Q are given in units of coulombs, r in metres, and F in newtons and there is no dielectric material between the charges. A dielectric material is one that reduces the electrostatic force when placed between charges. Furthermore, Coulomb's constant can be given by:

where = permittivity. When there is no dielectric material between the charges (for example, in free space or a vacuum),

Air is only very weakly dielectric and the value above for will work well enough with air between the charges. If a dielectric material is present, then

where is the dielectric constant which depends on the dielectric material. In a vacuum (free space), and thus . For air, . Typically, solid insulating materials have values of and will reduce electric force between charges. The dielectric constant can also be called relative permittivity, symbolized as in Wikipedia.

Highly charged particles close to each other exert heavy forces on each other; if the charges are less or they are farther apart, the force is less. As the charges move far enough apart, their effect on each other becomes negligible.

Any force on an object is a vector quantity. Vector quantities such as forces are characterized by a numerical magnitude (i. e. basically the size of the force) and a direction. A vector is often pictured by an arrow pointing in the direction. In a force vector, the direction is the one in which the force pulls the object. The symbol is used here for the electric force vector. If charges q and Q are either both positive or both negative, then they will repel each other. This means the direction of the electric force on q due to Q is away from Q in exactly the opposite direction, as shown by the red arrow in the preceding diagram. If one of the charges is positive and the other negative, then they will attract each other. This means that the direction of on q due to Q is exactly in the direction towards Q, as shown by the blue arrow in the preceding diagram. The Coulomb's equation shown above will give a magnitude for a repulsive force away from the Q charge. A property of a vector is that if its magnitude is negative, the vector will be equal to a vector with an equivalent but positive magnitude and exactly the opposite direction. So, if the magnitude given by the above equation is negative due to opposite charges, the direction of the resulting force will be directly opposite of away from Q, meaning the force will be towards Q, an attractive force. In other sources, different variations of Coulombs' Law are given, including vector formulas in some cases (see Wikipedia link and reference(s) below).

In many situations, there may be many charges, Q1, Q2, Q3, through Qn, on the charge q in question. Each of the Q1 through Qn charges will exert an electric force on q. The direction of the force depends on the location of the surrounding charges. A Coulomb's Law calculation between q and a corresponding Qi charge would give the magnitude of the electric force exerted by each of the Qi charges for i = 1 through n, but the direction of each of the component forces must also be used to determine the individual force vectors, . To determine the total electric force on q, the electric force contributions from each of these charges add up as vector quantities, not just like ordinary (or scalar) numbers.

The total electric force on q is additive to any other forces affecting it, but all of the forces are to be added together as vectors to obtain the total force on the charged object q. In many cases, there are billions of electrons or other charges present, so that geometrical distributions of charges are used with equations stemming from Coulomb's Law. Practically speaking, such calculations are usually of more interest to a physicist than an electrician, electrical engineer, or electronics hobbyist, so they will not be discussed much more in this book, except in the section on capacitors.

In addition to the electrostatic forces described here, electromagnetic forces are created when the charges are moving. These will be described later.

Reference(s):

- College Physics Volume 2 by Doug Davis, Saunders College Publishing, Orlando, FL, 1994

Next: Voltage, Current, and Power

Return to: Electronics Outline

Voltage, Current, and Power

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Basic Understanding

editExperiments show us that electric point charges attract or repel as calculated by Coulomb's law. Integrating (summing) over a distribution of points charges as they are assembled into a specific system configuration allows us to determine a scalar value defined as the electrical potential or electric field of a specific point. This mathematical definition is very useful in electronics circuit theory.

Voltage

- The potential difference between two test points resulting from the distribution of charge in the circuit, usually measured in volts.

Current

- Net amount of charge (coulombs) (number of electrons x electron charge) flowing past a specified point during a time interval (seconds), usually measured in Amps (1 Amp = 1 coulomb / 1 second). In typical components and systems the quantity of electrons is quite large and the aggregate charge flow is referred to as electricity.

Power

- Energy given in a certain amount of time, usually measured in watts.

Law of Charges

- Opposite charges attract while similar charges repel.

Inductance

- When electricity passes through a wire it creates a moving magnetic field around the wire. The typical unit of measure is Henrys.

Capacitance

- When electric fields or charge distributions are created in a physical system that stores recoverable energy, characteristics of the physical components which affect calculation of the electrical quantities are defined as capacitance. The base unit of measure is Farads, however microfarads (μF), are used much more often.

Resistance

- When potential difference creates movement of electrons between two points, some of the potential energy formerly available in the system is irreversibly transferred from the electric field or the electrons moving through the component via collisions with atoms and molecules within the material. Ohm's Law, V=IR, defines resistance as R=V/I where V is the voltage difference applied across the component, I is the resulting current flow in Amps, and R is a constant created by characteristics of the component which is calculated from the measured voltage loss of the measured current passing through the component.

Electric Field

editA charged particle such as a proton or electron may "feel" an electrical force on it in a certain environment. This force is typically due to the presence of other charges nearby. The force will have a direction and magnitude, and can be represented by a vector. (A vector is simply a quantity that represents the direction and magnitude of something.) The magnitude of the force depends on the charge of the particle, the charge on the particles around it, and how close or far away they are: Highly charged particles close to each other exert heavy forces on each other; if the charges are less, or they are farther apart, the force is less. The direction of the force depends on the location of the surrounding charges.

In describing the electrical environment at that location , it is said there is an electric field at that location. The electric field is defined as the force that a single unit of charge would feel at that location. In some systems of measurement, the unit of charge is the charge of a single proton; in others it is the coulomb. A coulomb is the charge of 6.24×1018 protons

The relationship between force and electric field for a single charged particle is given by the following equation:

The bold letters indicate vector quantities. This means that a charge q, in an electric field E, having a certain direction and a magnitude E, would have a force F on it, in the same direction and with a magnitude F. Considering only the magnitudes, the following would result from the definition.

E = F/q these are all magnitudes or numerical quantities

The net electric field E, at a location is due to the presence of all other charges nearby, similar to the net electric force F, if there was a charge q at that location. The contribution of one of these other charges to the total (or net) electric field is a vector E contribution, which for a point charge can be derived from Coulomb's Law. Distributions of charge density in various shapes may also yield vector E contributions to the total electric field, to be added in as vector quantities. Practically speaking, most electricians, electrical engineers, and other electrical circuit builders and hobbyists seldom do these sorts of electric field calculations. Electric field calculations of this sort are more of a theoretical physics or special applications problem, so these calculations are omitted here in favor of more applicable material. See Electric Field for such information on electric field formulas.

There is an electrical force on a charge only if there is a charge subject to the force at a location in an electric field. However, even if there is no such charge subject to the force, there could still be an electric field at a point. This means that an electric field is a property of a location or point in space and its electrical environment, which would determine what a charge q would "feel" if it were there.

Energy

editNow, a micro-physics review: Work is causing displacement (or movement) of an object or matter against a force. Energy is the ability to perform work like this. Energy can be kinetic energy or potential energy. Kinetic energy is the energy a mass has because it is moving. Potential energy in an object, in matter, in a charge or other situation has the ability to perform work or to be converted into kinetic energy or a different kind of potential energy.

A reason why a particle or a charge may have potential energy could be because it is located at a point in a force field, such as a gravitational field, electric field, or magnetic field. In the presence of such a field, gravity or electric or magnetic forces could cause the particle or charge to move faster or move against resistive forces, representing a conversion of potential energy to kinetic energy or work. The amount of potential energy it has would depend on its location. Moving from one location to another could cause a change in its potential energy.

For example, an object near the surface of the earth placed high would have a certain amount of gravitational potential energy based on its mass, location (height or altitude) in and strength of the Earth's gravitational field. If the object were to drop from this location (height) to a new lower location, at least some of its gravitational potential energy would be converted to kinetic energy, resulting in the object moving down. The difference in gravitational potential energy could be calculated from one location to another, but determining the absolute potential energy of the object is arbitrary, so ground level is chosen arbitrarily as the height where its gravitational potential energy equals zero. The potential energy at all other heights is determined from the mass of the object, location relative to the ground level, and strength of the gravitational field.

All energy values are numerical or scalar quantities, not vectors.

Electric Potential Energy

editSomewhat similarly, a charged particle at a certain point or location in an electrical environment (i. e. an electric field) would have a certain amount of electric potential energy based on its charge, location, and the electric field there, which could be based on quantity and locations of all other charges nearby. If the charge were to move from this location to a new location or point, it could cause a change in its electric potential energy. This difference in electric potential energy in the charge particle would be proportional to its charge and it could be an increase or a decrease. From measurements and calculations, one may be able to determine this difference in electric potential energy, but coming up with an absolute figure for its potential is difficult and typically not necessary. Therefore, in a manner somewhat similar to gravitational potential energy, an arbitrary location or point nearby, often somewhere in the electric circuit in question, is chosen to be the point where the electric potential energy would be zero, if the charge were there. Often the wiring, circuit, or appliance will be connected to the ground, so this ground point is often chosen to be the zero point. The electric potential energy at all other points is determined relative to the ground level. The SI unit of electric potential energy is the joule.

Electric Potential

editBecause the electric potential energy of a charged particle (or object) is proportional to its charge and otherwise simply dependent on its location (point where it's at), a useful value to use is electric potential. Electric potential (symbolized by V) at a point is defined as the electric potential energy (PE) per unit positive charge (q) that a charge would have at that given point (location). At a point a, the electric potential at a is given by:

Va = (PE of charge at a)/q

Somewhat analogously to an electric field, electrical potential is a property of a location and the electrical conditions there, whether or not there is a charge present there subject to these conditions. On the other hand, electric potential energy is more analogous to electric force in that for it to be present, there should be a subject charged particle or object which has that energy. Electric potential is often simply called potential by physicists. Because the SI unit of electric potential energy is the joule and because the SI unit of charge is the coulomb, the SI unit for electric potential, the volt (symbolized by V), is defined as a joule per coulomb (J/C).

Because electric potential energy is based on an arbitrary point where its value is set at as zero, the value of electric potential at a given point is also based on this same arbitrary zero point (reference point where the potential is set at zero). The potential at a given point a is then the difference between potentials from point a to the zero point, often called a ground node (or just ground).

Calculations of electric potential energy or electric potential based on Coulomb's Law are sometimes theoretically possible, such as might be for electric field calculations, but again these are of mostly theoretical interest and not often done in practical applications. Therefore, such calculations are also omitted here in favour of more applicable material.

Often it is of interest to compare the potentials at two different points, which we may call point a and point b. Then the electric potential difference between points a and b (Vab) would be defined as the electric potential at b minus the electric potential at a.

Vab = Vb - Va

The unit for electric potential difference is the volt, the same as for electric potential. Electric potential difference is often simply called potential difference by physicists. Under direct current (DC) conditions and at any one instant in time under alternating current (AC), potential and potential difference are numerical or scalar quantities, not vectors, and they can have positive or negative values.

Voltage

editVoltage is electric potential expressed in volts. Similarly, potential difference expressed in volts is often called voltage difference or often referred to as voltage across two points or across an electrical component. The terms electric potential, potential, and potential difference are terms more often used by physicists. Since these quantities are almost always expressed in volts (or some related unit such as millivolts), engineers, electricians, hobbyists, and common people usually use the term voltage instead of potential. Furthermore, in practical applications, electrical force, electric field, and electrical potential energy of charged particles are not discussed nearly as often as voltage, power, and energy in a macroscopic sense.

Additional note: The following explains why voltage is "analogous" to the pressure of a fluid in a pipe (although, of course, it is only an analogy, not exactly the same thing), and it also explains the strange-sounding "dimensions" of voltage. Consider the potential energy of compressed air being pumped into a tank. The energy increases with each new increment of air. Pressure is that energy divided by the volume, which we can understand intuitively. Now consider the energy of electric charge (measured in coulombs) being forced into a capacitor. Voltage is that energy per charge, so voltage is analogous to a pressure-like sort of forcefulness. Also, dimensional analysis tells us that voltage ("energy per charge") is charge per distance, the distance being between the plates of the capacitor. (More discussion is on page 16 of "Industrial Electronics," by D. J. Shanefield, Noyes Publications, Boston, 2001.)

Frequency

editWhen an electric circuit is operating in Direct Current (DC) mode, all voltages and voltage differences in the circuit are typically constant (do not vary) with time. When a circuit is operating under Alternating Current (AC) conditions, the voltages in the circuit vary periodically with time; the voltages are a sinusoidal function of time, such as V(t) = a sin (b t) with constant a and b, or some similar function. The number of times the period repeats (or "cycles") per unit time is called the frequency of V(t). Under DC conditions or at any one instant in time under AC, potential (or voltage) and potential difference (or voltage difference) are numerical or scalar quantities, not vectors, and they can have positive or negative values. However, in AC mode, the overall function of voltage with time V(t), can be expressed as a complex number or a phasor for a given frequency. The frequency can be expressed in cycles per second or simply sec-1, which is called Hertz (Hz) in SI units. Typical commercial electric power provided in the United States is AC at a frequency of 60 Hz (50 Hz for India).

Ground

editGround is shown on electronics diagrams, but it isn't really a component. It is simply the node which has been assigned a voltage of zero. It is represented by one of the symbols below. Technically, any single node can be assigned as ground, and other voltages are measured relative to it. However, the convention is to only assign it in one of two ways, related to the type of power supply. In a single supply situation, such as a circuit powered by a single battery, the ground point is usually defined as the more negative of the power source's terminals. This makes all voltages in the circuit positive with respect to ground (usually), and is a common convention. For a split-supply device, such as a circuit driven by a center-tapped transformer, usually the center voltage is defined as ground, and there are equal and roughly symmetrical positive and negative voltages in the circuit.

| Signal Ground |

Chassis Ground |

Earth Ground |

- Signal ground

- Ground for a signal. Since wires have a certain amount of resistance to them, ground points in a circuit aren't all at exactly the same voltage. It is important in practical circuit design to separate the power supply ground from the signal ground from the shielding ground, etc. In circuits where minimum noise is especially important, power regulator circuitry should have thick wires or traces connecting the grounds, in a sequence from the power supply to the "cleanest" ground at the output of the filters of the power supply, which will then be a "star point" for the grounds of the signal circuitry.

- Chassis ground

- A direct connection to the chassis of the device. This is used for EMI shielding and also for safety ground in line AC powered devices.

- Earth ground

- Used in radio or power distribution systems, a connection to the earth itself. Also the other end of the connection for the safety ground, since the power line voltage will seek a path through the earth back to the power line supply station. This was the original usage of the word "ground", and the more modern meaning of the word would have been called a "floating ground".

The earth ground symbol and signal ground symbol are often interchanged without regard to their original meanings. As far as signal-level electronics (and this book) is concerned, ground almost always means a signal ground or floating ground, not connected to the earth itself.

(see: http://www.prosoundweb.com/studyhall/rane/grounding/ground2.php)

Current

editElectric current, often called just current, is the movement of charge in a conductor (such as a wire) or into, out of, or through an electrical component. Current is quantified as a rate of positive charge movement past a certain point or through a cross-sectional area. Simply put, current is quantified as positive charge per unit time. However, since current is a vector quantity, the direction in which the current flows is still important. Current flow in a given direction can be positive or negative; the negative sign means that positive charges move opposite of the given direction. The quantity of current at a certain point is typically symbolized by a capital or small letter I with a designation which direction the current I is moving. The SI unit of current is the ampere (A), one of the fundamental units of physics. See ampere for the definition of ampere. Sometimes, ampere is informally abbreviated to amp. The definition of a coulomb (C), the SI unit of charge, is based on an ampere. A coulomb is the amount of positive charge passing a point when a constant one ampere current flows by the point for one second. The second is the SI unit of time. In other words, a coulomb equals an ampere-second (A·s). An ampere is a coulomb per second (C/s).

Conventional Current

editTypically, current is in a metal and constitutes movement of electrons which have negative charge; however, people initially thought that current had a positive charge. The result is that even though current is the flow of negative electrons and flows from the negative to the positive terminal of a battery, when people do circuit analysis they pretend that current is a flow of positive particles and flows from the positive to the negative terminal of a battery (or other power source). Actually, it is more complicated than this, since current can be made up of electrons, holes, ions, protons, or any charged particle. Since the actual charge carriers are usually ignored when analyzing a circuit, current is simplified and thought of as flowing from positive to negative, and is known as conventional current.

Analogy to pebble tossing: I have pebbles and I am throwing them into a basket. In doing this the basket gains pebbles and I lose pebbles. So there is a negative current of pebbles to the basket because it is gaining pebbles, and there is a positive current of pebbles to me because I am losing pebbles. In pebble tossing the currents have equal strength but in opposite directions.

Current I is represented in amperes (A) and equals x number of y

Power

editPower is energy per unit of time. The SI unit for power is the watt (W) which equals a joule per second (J/s), with joule being the SI unit for energy and second being the SI unit for time. When somebody plugs an appliance into a receptacle to use electricity to make that appliance function, that person provides electrical energy for the appliance. The appliance usually functions by turning that electrical energy into heat, light, or work — or perhaps converts it into electrical energy again in a different form. If this situation is ongoing, it is said that the receptacle or electric power company delivers power to the appliance. The current from the receptacle going in and out of the appliance effectively carries the power and the appliance absorbs the power.

Multiplying a unit of power by a unit of time would result in a unit that represents a quantity of energy. Therefore, multiplying a kilowatt by an hour gives a kilowatt-hour (kW·h), a unit often used by electrical power companies to represent an amount of electrical energy generated or provided to consumers. Oddly, in marketing and retail packaging, portable batteries are often rated in "mAh", which are normally units of power, but do not identify how much power the battery can supply. Rather, the mAh rating is always at the implied voltage defined by the battery's chemistry. For example, a common, premium quality 18650 Li-ion battery would be advertised/rated 3400 mAh, at most. Even though "3400 mAh" is in power units, Li-ion chemistry battery voltage is typically around 3.7 volts, and this does identify the battery as one that should be able to store about 3400 mAh x 3.7 volts = 12.6 mWh (milliwatt hours) of energy per charge.) Also oddly, in marketing and retail packaging, a larger (e.g. vehicle) battery is often advertised based on the "Amps" or "Cold Cranking Amps" (CCA) the battery can provide to indicate the maximum power it can deliver. Although Amps are not power units, these ratings do represent the amount of power that can be output.

For direct current (DC), power P can be calculated by multiplying the voltage and current, when they are known.

P = V I

Note that energy/charge is multiplied by charge/time to give energy/time. At any one point in time t in alternating current (AC) circuitry, power P(t) equals voltage V(t) times current I(t).

P(t) = V(t) I(t) at any one time t

Calculations of AC power averaged over time will be discussed under AC power.

Circuit

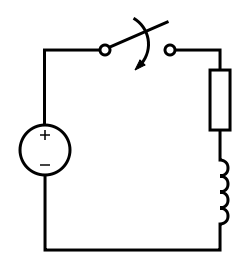

editAn electronic circuit is a system in which conventional current flows from the positive terminal of a source, through a load, to the negative terminal of the source. But the current will only flow when there is a closed path from the positive to negative terminal. If there is a discontinuity or an open circuit in its path, the current will not flow and hence the circuit will be non functional. The current does not flow since the open circuit acts like an infinite resistance.

Short Circuit

editA short circuit is another name for a node, although it usually means an unintentional node. Has current through it but no voltage across it.

Open Circuit

editHas potential across it but no current through it.

Properties of wires

editTheoretical circuit connection (wire) has no resistance or inductance. Real wires always have voltage over them if there is current flowing through them (resistance). On high frequencies there are measurable voltage potentials over wire links if there is flowing alternating current through wires (inductance like in inductors).

Basic Concepts

What is Electronics?

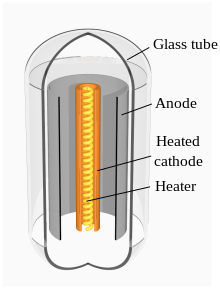

editElectronics is the study of flow of electrons in various materials or space subjected to various conditions. In the past, electronics dealt with the study of Vacuum Tubes or Thermionic valves, today it mainly deals with flow of electrons in semiconductors. However, despite these technological differences, the main focus of electronics remains the controlled flow of electrons through a medium. By controlling the flow of electrons, we can make them perform special tasks, such as power an induction motor or heat a resistive coil.

Plumbing Analogy: A simple way to understand electrical circuits is to think of them as pipes. Let's say you have a simple circuit with a voltage source and a resistor between the positive and negative terminals on the source. When the circuit is powered, electrons will move from the negative terminal, through the resistor, and into the positive terminal. The resistor is basically a path of conduction that resists the movement of electrons. This circuit could also be represented as a plumbing network. In the plumbing network, the resistor would be equivalent to a section of pipe, where the water is forced to move around several barriers to pass through, effectively slowing its flow. If the pipe is level, no water will flow in an organized fashion, since the pressure is equal throughout the pipe. However, if we tilt the pipe to a vertical position (similar to turning on a voltage source), a pressure difference is created (similar to a voltage difference) and the water begins flowing through the pipe. This flow of water is similar to the flow of electrons in a circuit.

Electricity

editTo understand electronics, you need to understand electricity and what it is. Basically, electricity is the flow of electrons due to a difference in electrical charge between two points. This difference in charge is created due to a difference in electron density. If you have a point where the electron density is higher than the electron density at another point, the electrons in the area of higher density will want to balance the charge by migrating towards the area with lower density. This migration is referred to as electrical current. Thus, flow in an electrical circuit is induced by putting more electrons on one side of the circuit than the other, forcing them to move through the circuit to balance the charge density.

Electric Charge

editObservations tell us that matter can either be electrically neutral (that is, have no net charge), or carry a positive or negative charge. On a microscopic level, a negative charge corresponds to an excess of electrons in the material (which each carry a 'unit' of negative charge), and a positive charge a shortage of electrons. We denote the charge of an object by , which is measured in Coulombs.

Coulomb's Law

editTwo objects that have the same type of charge are known to repel, whereas objects with opposite charges attract. The force between charged objects is given by Coulomb's Law:

where and are the charges of the two objects (positive or negative), is the distance between them, and a universal constant.

Electric field

editSuppose we have a fixed particle (or a collection of fixed particles), then we can calculate the force on any given (test) particle with charge by applying Coulomb's Law. There is a force at any point in space; we say that there is an electric field due to the (fixed) charges. The field at any point is equal to the net force on a charged particle divided by its charge, or:

Lorentz's Law

editWhen a charge in motion passes through a magnetic field, the magnetic field will push a positive charge upward and negative charge downward in the direction perpendicular to the initial direction traveled. The magnitude of the magnetic force on the charge is given by Lorentz's Law:

Electromagnetic Force

editThe sum of the Coulomb and Lorentz's Forces is called the ElectroMagnetic Force:

Electricity and Matter

editAll matter interacts with Electricity, and are divided into three categories: Conductors, Semi Conductors, and Non Conductors.

- Matter that conducts Electricity easily. Metals like Zinc (Zn) and Copper (Cu) conduct electricity very easily. Therefore, they are used to make Conductors.

- Matter that does not conduct Electricity at all. Non-Metals like Wood and Rubber do not conduct electricity so easily. Therefore, they are used to make Non-Conductors.

- Matter that conducts electricity in a manner between that of Conductors and Non-Conductors. For example, Silicon (Si) and Germanium (Ge) conduct electricity better than non-conductors but worse than conductors. Therefore, they are used to make Semi Conductors.

Electricity and Conductors

editNormally, all conductors have a zero net charge . If there is an electric force that exerts a pressure on the charges in the conductor to force charges to move in a straight line result in a stream of electric charge moving in a straight line

Voltage

edit- The pressure the electric force exert on the charges is called voltage denoted as V measured in Volt (V) and defined as the ratio of Work Done on Charge

Current

edit- The moving of straight lines of electric charges in the conductor is called current denoted as I measured in Ampere (A) and defined as Charge flow through an area in a unit of time

Conductance

edit- Conductance is defined as the ratio of current over voltage denoted as Y measured in mho

- or siemens (S)

Resistance

edit- Resistance is defined as the ratio of voltage over current denoted as R measured in Ohm

Generally, resistance of any conductor is found to increase with increasing temperature

For Conductor

- R = Ro(1 + nT)

For Semi Conductor

- R = Ro enT

When a conductor conducts electricity, it dissipates heat energy into the surrounding . This results in a loss of electric energy transmitted. If the electric supply energy is PV and the electric loss energy is PR Then the electric energy delivered:

- P = PV - PR

Black Body Radiation

editFurther experience with conductors that conduct electricity . It is observed that all conductors that conduct electricity exhibit

- Change in Temperature

- Release Radiant Heat Energy into the surrounding

Experiment

editConnect a conductor with an electric source in a closed loop . Plot the value I at different f to have a I - f diagram

Observation

editfor f<fo

- Current increasing with increasing f .

- Radiant heat is a wave travels at velocity v = λf carries energy E = m v2 .

for f=fo,

- Current stops increasing .

- Radiant heat is a wave travels at velocity v = c (speed of Light) carries energy E = hfo .

for f>fo,

- Current remains at the value of current at fo .

- Radiant heat is a wave travels at velocity v = c (speed of Light) carries energy E = h nfo

Conclusion

edit- All conductor that conducts Electricity has a threshold frequency fo

- The Radiant Heat Energy is a Light Wave of dual Wave Particle characteristic. Sometimes it behaves like Particle, sometimes it behaves like Wave

- At Frequency f > fo . The energy of the Light is quantized . it can only have the value of multiple integer of fo . E = hf = h nfo

Cells

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Cells

editA cell, or electrochemical cell, Galvanic cell or Voltaic cell, is a component used to store and provide electrical energy. The energy in a cell is stored as a chemical potential energy, and electrical energy can be extracted when the chemicals undergo a chemical reaction. A battery is the term used to refer to multiple cells that are used together as one unit, and can be connected in series, parallel or in a combination of series and parallel connections.

The properties of the cell can be determined by the chemistry of the cell (i.e. what it is made up of), and its physical design. Different chemistries will affect cell voltage, energy density, internal resistivity, and other factors. Physical design will affect the total cell energy capacity, total internal resistance and the shape and size of the cell. Generally, increasing the size of a cell, while maintaining the cell chemistry, will result in a greater energy capacity and lower internal resistance, and consequently a greater current supplying capability, and vice versa.

Cells are categorised as Primary (Dry) cells, and Secondary (Wet) cells, based on their chemistry. Primary cells are single-use and disposable, for example alkaline cells. Secondary cells are rechargeable, for example lead-acid cells.

- Cell: Two materials with a voltage difference between them. This causes current to flow, which does work. Electrons travel from the cathode, do some work, and are absorbed by the anode.

- Anode: Destination of electrons.

- Cathode: Source of electrons.

- ions: An atom with an imbalance of electrons.

- cell operation: The cell runs and electrons are depleted at the cathode and accumulate at the anode. This creates a reverse voltage which stops the flow of electrons.

- irreversible: At some point the voltage difference reactions between the cathode and anode will decrease to a point that the cell in unusable. At this point, in an irreversible cell, the voltage difference is irreplaceably lost, and the cell is of no further use.

- reversible: Able to run the cell backwards.

- rechargeable: In a rechargeable cell, when the voltage difference between the cathode and anode decreases, the cell can be recharged, thereby increasing the voltage difference to a suitable level to allow continued use.

- humid air will discharge cells.

- cells are usually made of toxic or corrosive substances, for example lead and sulphuric acid. Such substances have been known to explode.

- Electronegativity [16]

What is the relationship between voltage and electronegativity?

- Electronegativity is a concept in chemistry used to measure and predict the relative likelihood of a chemical reaction causing electrons to shift from one chemical to another resulting in ions and molecular bonds. A battery cell operates by allowing two chemicals to react and supply ions to the anode and cathode. When the supply of a reactant is consumed, the battery is dead. It no longer produces different electrical potential at the anode and cathode driven by the chemical reaction.

- Voltage is the electrical potential of a point due to surrounding measurable electric charge distributions and points as calculated by application Coulomb's Law. Voltage difference between two points connected by a conductor results in electron flow.

Resistors

Electronics | Foreword | Basic Electronics | Complex Electronics | Electricity | Machines | History of Electronics | Appendix | edit

Resistor

editA resistor is a block or material that limits the flow of current. The greater the resistance, the lower the current will be, assuming the same voltage imposed on the resistor. The hydraulic analogy of a resistor would be the pipe with water flowing through it. The wider the diameter of a pipe, the higher the water flow through the pipe, assuming the same pressure difference on the terminals of a pipe.

Resistor's Symbol

editResistors have two leads (points of contact) to which the resistor can be connected to an electrical circuit. A symbol for a resistor used in electrical circuit diagrams is shown below.

The endpoints at the left and right sides of the symbol indicate the points of contact for the resistor. The ratio of the voltage to current will always be positive, since a higher voltage on one side of a resistor is a positive voltage, and a current will flow from the positive side to the negative side, resulting in a positive current. If the voltage is reversed, the current is reversed, leading again to a positive resistance.

Resistance

editResistance is a characteristic of Resistor indicates the measurement of current opposition . Resistance has a symbol R measured in Ohm (Ω) . The ratio of voltage to current is referred to as Ohm's Law, and is one of the most basic laws that govern electronics.

An ohm is the amount of resistance which passes one ampere of current when a one volt potential is placed across it. (The ohm is actually defined as the resistance which dissipates one watt of power when one ampere of current is passed through it.)

Resistance can vary from very small to very large. A superconductor has zero resistance, while something like the input to an op-amp can have a resistance near 1012 Ω, and even higher resistances are possible.

Resistance and Temperature

editFor most materials, resistance increases with increasing Temperature

- For Conductor .

- For Semi Conductor .

Resistance and Electric Power Loss

editResistance converts Electrical Energy into Heat this causes Electric Energy Loss.

NOTE : Resistors which dissipate large amounts of power are cooled so that they are not destroyed, typically with finned heatsinks.

If Electric Energy Supply is Pv and Electric Energy Loss is Pr Then, Electric Energy Delivered is

The ratio of Electric Energy Delivered over Electric Energy Supplied indicates the Efficiency of Electric Power Supply

Resistor's Labeling (See also Identification)

editA manufactured resistor is usually labeled with the nominal value (value to be manufactured to) and sometimes a tolerance. Rectangular resistors will usually contain numbers that indicate a resistance and a multiplier. If there are three or four numbers on the resistor, the first numbers are a resistance value, and the last number refers to the number of zeroes in the multiplier. If there is an R in the value, the R takes the place of the decimal point.

- Examples

- 2003 means 200×103 = 200kΩ

- 600 means 60×100 = 60Ω

- 2R5 means 2.5Ω

- R01 means 0.01Ω

Cylindrical resistors (axial) usually have colored bands that indicate a number and a multiplier. Resistance bands are next to each other, with a tolerance band slightly farther away from the resistance bands. Starting from the resistance band side of the resistor, each colour represents a number in the same fashion as the number system shown above.

Colour System

Black Brown Red Orange Yellow Green Blue Violet Grey White 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Clue : B.B.ROY of Great Britain was a Very Good Worker. Additional Colours: A gold band in the multiplier position means 0.1, but means a 5% tolerance in the tolerance position. A silver band in the multiplier position means 0.01, but means 10% in the tolerance position.

Resistor's Construction

editThe resistance R of a component is dependent on its physical dimension and can be calculated using:

where

- ρ is the electrical resistivity (resistance to electricity) of the material,

- L is the length of the material

- A is the cross-sectional area of the material.

If you increase ρ or L you increase the resistance of the material, but if you increase A you decrease the resistance of the material.

Resistivity of the Material

editEvery material has its own resistivity, depending on its physical makeup. Most metals are conductors and have very low resistivity; whereas, insulators such as rubber, wood, and air all have very high resistivity. The inverse of resistivity is conductivity, which is measured in units of Siemens/metre (S/m) or, equivalently. mhos/metre.

In the following chart, it is not immediately obvious how the unit ohm-meter is selected. Considering a solid block of the material to be tested, one can readily see that the resistance of the block will decrease as its cross-sectional area increases (thus widening the conceptual "pipe"), and will increase as the length of the block increases (lengthening the "pipe"). Given a fixed length, the resistance will increase as the cross-sectional area decreases; the resistance, multiplied by the area, will be a constant. If the cross-sectional area is held constant, as the length is increased, the resistance increases in proportion, so the resistance divided by the length is similarly a constant. Thus the bulk resistance of a material is typically measured in ohm meters squared per meter, which simplifies to ohm - meter (Ω-m).

Conductors Ω-m (Ohm-meter) Silver 1.59×10-8 Copper 1.72×10-8 Gold 2.44×10-8 Aluminum 2.83×10-8 Tungsten 5.6×10-8 Iron 10×10-8 Platinum 11×10-8 Lead 22×10-8 Nichrome 1.50×10-6 (A nickel-chromium alloy commonly used in heating elements) Graphite ~10-6 Carbon 3.5×10-5 Semiconductors Pure Germanium 0.6 Pure Silicon 640 Common purified water ~103 Ultra-pure water ~105 Pure Gallium Arsenide ~106 Insulators Diamond ~1010 Glass 1010 to 1014 Mica 9×1013 Rubber 1013 to 1016 Organic polymers ~1014 Sulfur ~1015 Quartz (fused) 5 to 75×1016 Air very high

Silver, copper, gold, and aluminum are popular materials for wires, due to low resistivity. Silicon and germanium are used as semiconductors. Glass, rubber, quartz crystal, and air are popular dielectrics, due to high resistivity.

Many materials, such as air, have a non-linear resistance curve. Normal undisturbed air has a high resistance, but air with a high enough voltage applied will become ionized and conduct very easily.

The resistivity of a material also depends on its temperature. Normally, the hotter an object is, the more resistance it has. At high temperatures, the resistance is proportional to the absolute temperature. At low temperatures, the formula is more complicated, and what counts as a high or low temperature depends on what the resistor is made from. In some materials the resistivity drops to zero below a certain temperature. This is known as superconductivity, and has many useful applications.

(Some materials, such as silicon, have less resistance at higher temperatures.)

For all resistors, the change in resistance for a small increase in temperature is directly proportional to the change in temperature.

Current passing through a resistor will warm it up. Many components have heat sinks to dissipate that heat. The heatsink keeps the component from melting or setting something on fire.

Length

editThe length of an object is directly proportional to its resistance. As shown in the diagram below, 1 unit cubed of material has 1 ohm of resistance. However, when 4 units are stacked lengthwise and a connection is made to the front and back sides respectively, the total resistance is 4 ohms. This is because the length of the unit is 4, whereas the cross-sectional area remains 1. However, if you were to make connections on the sides, the exact opposite would be true: the cross-sectional area would be 4 and the length 1, resulting in 0.25 ohms total resistance.

Cross-Sectional Area

editIncreasing area is the same as having resistors in parallel, so as you increase the area you add more paths for current to take.

The resistance of a material is inversely proportional to its cross-sectional area. This is shown in the diagram below, where 1 unit cubed has one ohm of resistance. However, if 4 units cubed are stacked on top of each other in the fashion such that there is 4 units squared of cross-sectional area, and the electrical connections are made to the front and back such that the connections are on the largest sides, the resultant resistance would be 0.25 ohms.

Additional note: There are two reasons why a small cross-sectional area tends to raise resistance. One is that the electrons, all having the same negative charge, repel each other. Thus there is resistance to many being forced into a small space. The other reason is that they collide, causing "scattering," and therefore they are diverted from their original directions. (More discussion is on page 27 of "Industrial Electronics," by D. J. Shanefield, Noyes Publications, Boston, 2001.)

Example

editFor instance, if you wanted to calculate the resistance of a 1 cm high, 1 cm wide, 5 cm deep block of copper, as shown in the diagram below:

You would first need to decide how it's oriented. Suppose you want to use it from front to back (lengthwise), like a piece of wire, with electrical contacts on the front and rear faces. Next you need to find the length, L. As shown, it is 5 cm long (0.05 m). Then, we look up the resistivity of copper on the table, 1.6×10-8 Ω-meters. Lastly, we calculate the cross-sectional area of the conductor, which is 1 cm × 1 cm = 1 cm2 (0.0001 m2). Then, we put it all in the formula, converting cm to m:

units m2 cancel:

Which, after evaluating, gives you a final value of 8.0×10-6 Ω, or 8 microohms, a very small resistance. The method shown above included the units to demonstrate how the units cancel out, but the calculation will work as long as you use consistent units.

- Internet Hint: Google calculator can do calculations like this for you, automatically converting units. This example can be calculated with this link: [17]

Properties of the material

edit- Wirewound: Used for power resistors, since the power per volume ratio is highest. These usually have the lowest noise.

- Carbon Film: These are easy to produce, but usually have lots of noise because of the properties of the material.

- Metal Film: These resistors have thermal and voltage noise attributes that are between carbon and wirewound.

- Ceramic: Useful for high frequency applications.

Resistor Connection

editResistors in Series

editResistors in series are equivalent to having one long resistor. If the properties of two resistors are equivalent, except the length, the final resistance will be the sum of the two construction methods:

This means that the resistors add when in series.

- Christmas tree lights are usually connected in series, with the unfortunate effect that if one light blows, the others will all go out (This happens because the circuit is not complete, if a circuit is not complete then the current cannot flow, hence the light bulbs all go out). However, most modern Christmas light strings have built in shunt resistors in parallel to the bulb, so that current will flow past the blown light bulb.

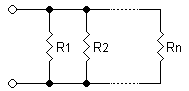

Resistors in Parallel

editIn a parallel circuit, current is divided among multiple paths. This means that two resistors in parallel have a lower equivalent resistance than either of the parallel resistors, since both resistors allow current to pass. Two resistors in parallel will be equivalent to a resistor that is twice as wide:

Since conductances (the inverse of resistance) add in parallel, you get the following equation:

For example, two 4 Ω resistors in parallel have an equivalent resistance of only 2 Ω.

To simplify mathematical equations, resistances in parallel can be represented with two vertical lines "||" (as in geometry). For two resistors the parallel formula simplifies to:

Combinations of series and parallel

editResistors in parallel are evaluated as if in a mathematical set of "parentheses." The most basic group of resistors in parallel is evaluated first, then the group in series with the new equivalent resistor, then the next group of resistors in parallel, and so on. For example, the above portion would be evaluated as follows:

Resistor variations

edit- Variable Resistor or Potentiometer

- Variable resistors are tunable, meaning you can turn a dial or slide a contact and change the resistance. They are used as knobs to control the volume of a stereo, or as a dimmer for a lamp. The term Potentiometer is often abbreviated as 'pot'. It is constructed like a resistor, but has a sliding tap contact. Potentiometers are used as Voltage Dividers. It is rare to find a variable resistor with only two leads. Most are potentiometers with three leads, even if one is not connected to anything.

- Rheostat

- A variation of the potentiostat with a high current rating, which is used to control the amount of power going through a load, such as a motor.

- Thermistor

- Temperature-sensitive resistor, in which the resistance decreases as the temperature rises. They are used in fire alarms, so if things get too hot the current rises and trips a switch that sounds an alarm.

- LDR (Light Dependent Resistor) or Photoresistor

- A resistor which changes values depending on the amount of light shining on its surface. The resistance decreases as the amount of light increases. They are used in street lamps, so when it gets dark the current decreases and turns on the street lamp.

Applications

edit- Voltage division / Attenuation: Sometimes a voltage will be too large to measure, so a means to linearly reduce the voltage is required. Placing two resistors in series to ground will provide a point in the middle to tap. Resistor RA is placed between the input voltage and the output node, and the resistor RB is placed between the output node and ground. This creates a voltage divider to lessen the output voltage. Typically, the resistors are near the value of ~10kΩ. The Thevenin model of the circuit gives an output resistance ROUT = RA||RB. A larger output resistance will more likely be affected by the input resistance of the measuring circuit (this is a desired effect in the transistor biasing circuits). Placement of the voltage divider should be close to the measuring circuit, to minimize noise (in this arrangement, it will be also lessened Rb/(Ra + Rb) times). The output voltage of the voltage divider is

- Pull-up / Pull-down: If there is nothing to drive a signal node, the node will be left "floating" (for example, such a situation occurs at the trigger input of a car alarm system when the driver has switched off the internal lamp). This may lead to unintended values being measured, or causing side-effects when the voltage is propagated down the remainder of the circuit. To prevent this, a relatively high value resistor (usually ~10kΩ to ~1MΩ) is placed between the node and ground (pull-down) or a high voltage (pull-up) to bring the voltage of the "floating" node near to the voltage it is being pulled. A resistive voltage divider is another example where the upper resistor "pulls" the output point up toward the input voltage while the lower resistor "pulls" the output point toward the ground. This idea is evolved in the circuit of a resistive voltage summer (for example, the resistors R1 and R2 of an op-amp inverting amplifier) supplied by two voltages (VIN and -VOUT) having opposite polarities. The two voltage sources "pull" the output point in opposite directions; as a result, if R2/R1 = -VOUT/VIN, the point becomes a virtual ground. Placement of a pull-up or pull-down resistor does not have a significant effect on the performance of the circuit, if they have high resistances.

- Current limiting / Isolation: In order to protect circuits from conditions that may cause too much current in a device, a current limiting resistor is inserted in the middle of the circuit. A digital input to a microcontroller may benefit from a current limiting resistor. The inputs to modern microcontrollers have protection circuitry built in that will protect the input from an overvoltage condition, provided that the current is small enough. For instance, a common microcontroller will be capable of withstanding 20mA. If there are 12V nets on a circuit board, or in a system, the digital input will benefit from a 350Ω resistor (refer to calculation below). Usually a slightly larger resistance is used in practice, but too large of a resistor will cause noise, and may prevent the input from being able to read the voltage. It is good practice to place the resistor as close as possible to the microcontroller input, so that an accidental short on the board will mean that the microcontroller input is likely still protected.

- Line termination / Impedance matching: The properties of an electric wave propagating through a conductor (such as a wire) create a reflection, which can be viewed as unwanted noise. A reflection can be eliminated by maximizing the power transfer between the conductor and the termination resistor. By matching the resistance (more importantly the impedance ), the wave will not cause a reflection. The voltage of the echo V_r is calculated below in reference to the original signal V_o as a function of the conductor impedance Z_C and the terminator impedance Z_T. As the name implies, the termination resistor goes at the end of the conductor.

- Current sensing: Measurement of a current cannot be done directly. There are three major ways to measure a current: a resistor, a hall sensor, and an inductor. The hall sensor and inductor use a property of the magnetic field to sense the current through a nearby conductor. According to Ohm's law, if a current I flows through a resistor R, a voltage V = R.I appears across the resistor. Therefore, the resistor can act as a passive current-to-voltage converter. In this arrangement, the resistor should have a very low value (sometimes on the order of ~0.01Ω), so it does not affect the current flow or heat up; however, a smaller value has a lower voltage to read, which means more noise may be introduced. This contradiction is solved in the circuit of an active current-to-voltage converter where the resistor may have a significant resistance as an op-amp compensates the "undesired" voltage drop across it (unfortunately, this remedy may be applied only in low-current measurements). The current sense resistor should be placed as close as possible to where the measurement occurs, in order not to disturb the circuit.

- Filtering: Filtering is discussed later, after an introduction to capacitors and inductors. Filters are best placed close to where measurement takes place.

Specifications

editResistors are available as pre-fabricated, real-world components. The behavior of such components deviates from an ideal resistor in certain ways. Therefore, real-world resistors are not only specified by their resistance, but also by other parameters. In order to select a manufactured resistance, the entire range of specifications should be considered. Usually, exact values do not need to be known, but ranges should be determined.

Nominal Resistance

editThe nominal resistance is the resistance that can be expected when ordering a resistor. Finding a range for the resistance is necessary, especially when operating on signals. Resistors do not come in all of the values that will be necessary. Sometimes resistor values can be manipulated by shaving off parts of a resistor (in industrial environments this is sometimes done with a LASER to adjust a circuit), or by combining several resistors in series and parallel.

Available resistor values typically come with a resistance value from a so called resistor series. Resistor series are sets of standard, predefined resistance values. The values are actually made up from a geometric sequence within each decade. In every decade there are supposed to be resistance values, with a constant step factor. The standard resistor values within a decade are derived by using the step factor

rounded to a two digit precision. Resistor series are named E, according to the used value of in the above formula.

n Values/Decade Step factor i Series

----------------------------------------

6 1.47 E6

12 1.21 E12

24 1.10 E24

48 1.05 E48

For example, in the E12 series for , the resistance steps in a decade are, after rounding the following 12 values:

1.00, 1.20, 1.50, 1.80, 2.20, 2.70, 3.30, 3.90, 4.70, 5.60, 6.80, and 8.20

and actually available resistors from the E12 series are for example resistors with a nominal value of 120Ω or 4.7kΩ.

Tolerances

editA manufactured resistor has a certain tolerance to which the resistance may differ from the nominal value. For example, a 2kΩ resistor may have a tolerance of ±5%, leaving a resistor with a value between 1.9kΩ and 2.1kΩ (i.e. 2kΩ±100Ω). The tolerance must be accounted for when designing circuits. A circuit with an absolute voltage of 5V±0.0V in a voltage divider network with two resistors of 2kΩ±5% will have a resultant voltage of 5V±10% (i.e. 5V±0.1V). The final resistor tolerances are found by taking the derivative of the resistor values, and plugging the absolute deviations into the resulting equation.

The above mentioned E-series which are used to provide standardized nominal resistance values, are also coupled to standardized nominal tolerances. The fewer steps within a decade there are, the larger the allowed tolerance of a resistor from such a series is. More precises resistors, outside of the mentioned E-series are also available, e.g. for high-precision measurement equipment. Common tolerances, colors and key characters used to identify them are for example:

Series Values/Decade Tolerance Color Code Character Code

--------------------------------------------------------------

E6 6 ±20% [none] [none]

E12 12 ±10% silver K

E24 24 ±5% gold J

E48 48 ±2% red G

- - ±1% brown F

- - ±0.5% - D

- - ±0.25% - C

- - ±0.1% - B

Resistor manufacturers can benefit from this standardization. They manufacture resistors first, and afterwards they measure them. If a resistor does not meet the nominal value within the defined tolerance of one E-series, it might still fit into a lower series, and doesn't have to be thrown away, but can be sold as being compliant to that lower E-series standard. Although typically at a lower price.

Series: Resistors that combine in series add the nominal tolerances together.

- Derivation:

- Example: For two resistors in series RA = 1.5kΩ±130Ω and RB = 500Ω±25Ω, the tolerance is 130Ω + 25Ω, resulting in a final resistor value RT = 2kΩ±155Ω.

Parallel: Resistors that combine in parallel have a combined tolerance that is slightly more complex.

- Derivation:

- Example: For two resistors in parallel RA = 1.5kΩ±130Ω and RB = 500Ω±25Ω.

Power Rating

editBecause the purpose of a resistor is to dissipate power in the form of heat, the resistor has a rating (in watts) at which the resistor can continue to dissipate before the temperature overwhelms the resistor and causes it to overheat. When a resistor overheats, the material begins to melt away, which will cause the resistance to increase (usually), until the resistor breaks.

Operating Temperature

editRelated to power rating, the operating temperature is the temperature that the resistor can continue to operate before being destroyed.

Maximum Voltage

editIn order to avoid sparkovers or material breakdown a certain maximum voltage over a resistor must not be exceeded. The maximum voltage is part of a resistor's specification, and typically a function of the resistor's physical length, distance of the leads, material and coating.

For example, a resistor with a maximum operating voltage of 1kV can have a length in the area of 2", while a 0.3" resistor can operate under up to several tens of volts, probably up to a hundred volts. When working with dangerous voltages it is essential to check the actual specification of a resistor, instead of only trusting it because of the length.

Temperature Coefficient

editThis parameter refers to the constant in which the resistance changes per degree Celsius (units in C-1). The change in temperature is not linear over the entire range of temperatures, but can usually be thought of as linear around a certain range (usually around room temperature). However, the resistance should be characterized over a large range if the resistor is to be used as a thermistor in those ranges. The simplified linearized formula for the affect on temperature to a resistor is expressed in an equation:

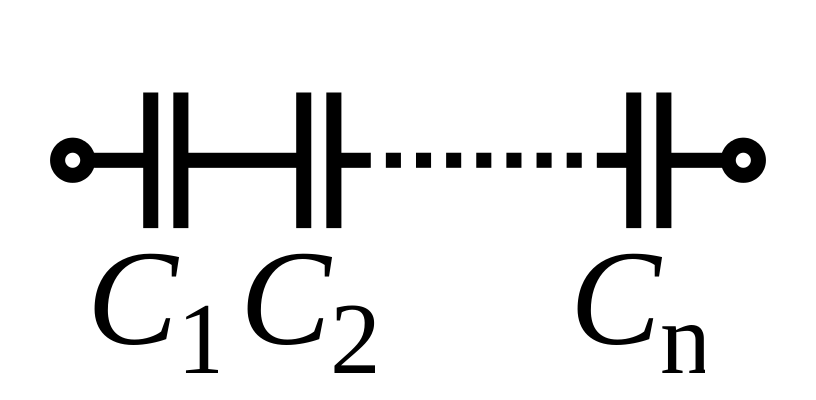

Capacity and Inductance

editReal world resistors not only show the physical property of resistance, but also have a certain capacity and inductance. These properties start to become important, if a resistor is used in some high frequency circuitry. Wire wound resistors, for example, show an inductance which typically make them unusable above 1kHz.

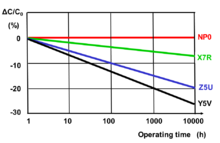

Packaging