The Futility of Personal Data Security: How Data Breaches Reveal Fundamental Issues in Data Harvesting

The advent of the World Wide Web and the subsequent technology that built off of its eventual widespread availability in the twenty-first century, served to connect people from one end of the world to the next. And while no one can disparage the tremendous benefits the internet has brought, the other side of that gleaming technological coin should also be carefully considered. As limitless as the internet seems, the issues it brings to rise are as well. One of the most insidious issues that has come to rise alongside the progression of the internet is the sheer amount of information that people willingly, and often obligatorily provide about themselves.

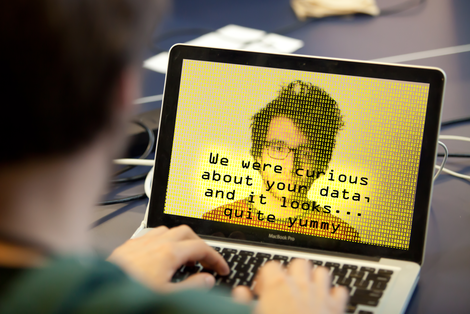

Since the scandal of Facebook’s involvement with Cambridge Analytica in the 2016 election, companies selling personal information to third party apps and data harvesters have come into the awareness of the general public. However, the increased awareness of data tracking does not mean that the average person, specifically the average American, understands the extent of their data being tracked, and where this data may be going. Moreover, 2017 studies from the Pew Research Center have shown that a large percentage of Americans are unsure or misinformed about many topics on proper cybersecurity.[1] Oftentimes, lack of awareness also comes from assumptions that basic security practices will prevent sites from collecting an individual’s data, or that a site only has the data that people have consciously entered, such as an individual’s username, password, date of birth, etc. that is often the basic sign-up procedure for most sites on the internet.

However, this is barely the tip of what sites, especially the larger social media sites such as Facebook and its affiliates Instagram and WhatsApp collect, and this is often revealed by bad-faith data breaches and the information those behind the breaches gain from site’s databases. Observing some of the largest data breaches, such as the Yahoo[2] and Cambridge Analytica breaches lays out how often these breaches are out of the hands of the individual. Adding to the fact that Statista has reported an increase in the number of data breaches yearly, reform at a national level on what individual data can be collected in the U.S., like the General Data Protection Regulation (or GDPR) in the European Union, becomes a clear necessity.

Instances of data breaches have been occurring for as long as data has been collected, but the advent of the internet and subsequent movement of most data into digital storage has only served to increase the number of data breaches per year, while the number of people impacted per data breach has exponentially risen. While data breaches from stolen files and leaked information from employees was not unheard of in the past, data collected and stored online is uniquely vulnerable to anyone with malicious intent and the knowledge of getting past security systems. Granted, it is not the easiest thing in the world to get past robust security systems in place to protect people’s information, but security has not stopped–or even slowed successful breaches, regardless of any security advent. As shown in data collected by Statista since 2005, the number of data compromises has increased tenfold, from 157 instances in 2005 impacting 66.9 million records, to peaking in 2021 at 1,862 compromises and 298.08 million records impacted.[3] This erosion of privacy was inevitable in a landscape where personal information has become a commodity to sell to the highest bidder, often to gain insight into user bases to manipulate individual choices.

The most spotlighted instance of personal information being used to manipulate user opinions was the data breach by whistleblower Christopher Wylie, revealing Cambridge Analytica’s data harvesting methods of Facebook users and subsequent targeted posts to sway voters during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. As explained by Wylie in an interview regarding the purpose of Cambridge Analytica, “We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons. That was the basis the entire company was built on." [4]

This was a breakdown of privacy at an unprecedented level, and the bigger issue was how Facebook handled the data breach following the reveal of Cambridge Analytica’s harvesting of millions of users’ data. Facebook was exceedingly slow in ensuring the security of its user’s data following the breach, only issuing a letter ordering the harvested data to be deleted months after the fact, and doing little to nothing to ensure that the data was out of third-party hands. [4] As data protection specialist and forefront investigator into Facebook’s involvement Paul-Olivier Dehaye explains, despite the evidence that Facebook was not doing its due diligence following the breach, “Facebook has denied and denied and denied this. It has misled MPs and congressional investigators…. It has a legal obligation to inform regulators and individuals about this data breach, and it hasn’t." [4] Unfortunately, Facebook’s refusal to acknowledge the data breach for what it was, and subsequent lack of transparency regarding what happened to that data afterwards, is a common practice for companies to downplay their involvement and severity of a breach.

Currently, there is no federal standard of what is required of companies to disclose to the impacted persons of a data breach, and while most states have passed laws regarding transparency surrounding breaches, the requirements and charges for failure in compliance often vary. Troy Hunt, a cybersecurity expert, provided overviews of companies’ responses to data breaches while outlining what the best practices are when responding to a data breach, and where a companies’ moral responsibilities lie. From his comparisons, it becomes evident that while a few companies will respond promptly with transparency upon a data breach, it’s much more likely for a company to attempt to evade the issue until it has no choice but to address it.[5]

In addition, companies will often attempt to obfuscate the importance of the data that was exposed, such as making statements assuring customers that no credit card or payment information tied to an account has been stolen, just e-mail addresses and similar, seemingly non-consequential information in comparison. However, the unencrypted information found through a data breach, especially a user’s personal information, is always connected to other aspects of a user’s online presence, and creates vulnerabilities in more than just the original breached site. In the experience of Megan Clifford, a victim of T-Mobile’s 2017 data breach, hackers getting access to her phone number lead to their ability to access almost all of her accounts, as Alix Langone reported, “Now that someone had her phone number, they could get into her bank account and gain access the common apps she had on her phone, including Venmo and iTunes.”[6] Aside from porting scams like the one Clifford faced, access to email lists often spawn targeted phishing scams, or can be sold to another party for further exploitation.

Without standardization on consequences of breaches, compensation and responsibility is often determined on a case-to-case basis, and the impacted users will rarely have legal recourse regarding stolen data, as the lower courts have struggled to define harm when it comes to data breaches. As Solove and Citron summarized in a thesis published in The Texas Law Review:

In the past two decades, plaintiffs in hundreds of cases have sought redress for data breaches caused by inadequate data security. In most instances, there is evidence that the defendants failed to use reasonable care in securing plaintiffs’ data. The majority of the cases, however, have not turned on whether the defendants were at fault. Instead, the cases have been bogged down with the issue of harm. No matter how derelict defendants might be with regard to security, no matter how much warning defendants have about prior hacks and breaches, if plaintiffs cannot show harm, they cannot succeed in their lawsuits (739).[7]

The thesis further provides examples of cases in which plaintiffs have failed in their lawsuits, even with clear evidence of potential harm from the data disseminated by the breach, because the courts could not define the harm in a concrete manner (779).[7] With the sheer amount of information that is being collected through usage of the internet on the individual, and the modern-day inaccessibility to existing without an online footprint in some way, the responsibility of bearing the burden of data breaches should not be left on the individual being affected. However, without regulation surrounding the data being collected and how this data is meant to be treated in the first place, the onus in the U.S. lands on the individual to handle.

Regulations in personal data privacy clearly need to be passed and fortunately, a functioning example to structure federal regulations already exists in the form of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a European Union regulation approved by the European Union in May of 2018. The goal of the GDPR is to put the power of personal data back into the hands of users to minimize the risk and more forward with transparency in the event a data breach was to occur. The GDPR has proven to be complex for companies to fall under compliance but essentially, it aims to allow users to request information on what data a site is collecting, and permanent erasure of data records if desired. The GDPR also has fines that may be levied to companies that fail to report data breaches within a timely and in a transparent manner, with delays incurring heavier fines the more time that passes since the initial notice of a breach.

Security expert Saryu Nayyar writes for the implementation of something akin to the GDPR in her Forbes article, “For simplicity’s sake, businesses want one unified and standard set of regulatory requirements to meet. This is precisely what the GDPR did, replacing numerous disparate regulations instituted by various EU member states.”[8] As she points out in the article, states have begun to pass laws surrounding data breaches, but the lack of standardization creates a difficult environment for companies to be compliant, and loopholes for ones that are not looking to be. Users in the U.S. have seen the effects of the GDPR from companies that have had to change their privacy policies to comply with the GDPR, and federal regulations regarding data privacy exist for specific sets of data already, like the FTC’s regulations for breaches in medical records. With these systems already in place and functioning, unified regulation is less unimaginable.

Like any market, data collection needs to be regulated and have enforced rules in place to protect the consumers from bad business practices, whether intentionally malicious or otherwise. And while the necessity is becoming more of a forefront issue, there has yet to be any significant change on a federal level regarding data collection and response to data breaches. Until change is demanded enough, it is ultimately up to the individual in the U.S. to protect their own data and information accessible on the internet. Cybersecurity experts recommend using unique and strong passwords for every account created with two factor authentication enabled, and to manage those under a password manager. In addition, investing in a VPN to obscure internet activity and IP addresses from providers and affiliated companies is good practice, as is using internet browsers that do not profit from collecting user data. However, this is ultimately a band-aid on a larger issue of unnecessary and excessive data collection, which only something akin to the GDPR passing could even begin to address.

References

edit- ↑ Olmstead, Kenneth, and Aaron Smith. “What the Public Knows about Cybersecurity.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 22 Mar. 2017,

- ↑ Brown, Shelby. “Robinhood data breach is bad, but we've seen much worse.” CNET. Nov, 2021./

- ↑ Statista. “Cyber Crime: Number of Compromises and Victims in U.S. 2005-HI 2022.” Statista, 31 Aug. 2022.

- ↑ a b c Cadwallader, Carole, and Graham-Harrison, Emma. “Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach.” The Guardian. Mar, 2018.

- ↑ Hunt, Troy. Data breach disclosure 101: How to succeed after you've failed. March, 2017. https://www.troyhunt.com/data-breach-disclosure-101-how-to-succeed-after-youve-failed/

- ↑ Langone, Alexandra, "Personal Privacy And Data Security In The Age Of The Internet" (2017). CUNY Academic Works. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/506

- ↑ a b Solove, Daniel J, and Danielle Keats Citron. “Risk and Anxiety: A Theory of Data-Breach Harms.” Texas Law Review, vol. 96, Dec. 2017, pp. 737–786.

- ↑ Nayyar, Saryu. “Is It Time For a U.S. Version of GDPR?” Forbes. February, 2022.