Survey of Communication Study/Chapter 6 - Communication Research

Communication Research

editChapter Objectives: |

One stereotype about college students is that they do not have a lot of extra money to spend. As a result, we have witnessed our students conduct communication research in order to increase their cashflow, and most of them didn't even know they were doing it. What do we mean by this? Many of our students are allotted a certain amount of money by their parents, financial aid, and jobs to pay for school, housing, and extracurricular activities. When money starts to become scarce, many of our students go to their parents to see if they will provide more money. What does this have to do with communication research? Because when these same students have asked for money from their parents in the past, they theorize what communication messages might work in order to get more. For example, if a student asked for money from their parents last semester because they said they were running out of food, and it worked, they might do that again in order to get more money. What is happening is that these students are developing hypotheses regarding what communication behaviors will work to influence their parents. If the behaviors work, it validates the hypothesis. If the behaviors don't work, students can learn from this and adjust their behaviors in future exchanges to obtain a different outcome. It is likely you engage in these types of communication research activities on a daily basis.

Likely you have engaged in basic levels of Communication research without even knowing it. Remember our discussion in the last chapter that theory is “a way of framing an experience or event—an effort to understand and account for something and the way it functions in the world” (Foss, Foss & Griffin, 8). Well, we generally do not understand how something functions in the world unless we have had some level of experience with it, and then evaluate the outcome of that experience. Have you ever planned out what you would say and do to persuade someone to go on a date? Have you ever intentionally violated the communicative expectations (such as arriving late or forgetting to do a favor) of a friend, “just to see what would happen?” While we do not consider these to be examples of formal Communication research, they do reveal what Communication research is about. Remember our discussion in Chapter 1, those of us who study Communication are interested in researching “who says what, through what channels (media) of communication, to whom, [and] what will be the results?” (Smith, Lasswell and Casey 121).

The term “research” often conjures up visions of a mad scientist dressed in a white lab coat working through the night with chemicals, beakers, and gases on his/her latest scientific experiment. But how does this measure up with the realities of researching human communication? Researching communication presents its own set of challenges and circumstances that must be understood to better conceptualize how we can further our understanding of the ways we communicate with one another.

Doing Communication Research

editStudents often believe that researchers are well organized, meticulous, and academic as they pursue their research projects. The reality of research is that much of it is a hit-and-miss endeavor. Albert Einstein provided wonderful insight to the messy nature of research when he said, “If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?” Because a great deal of Communication research is still exploratory, we are continually developing new and more sophisticated methods to better understand how and why we communicate. Think about all of the advances in communication technologies (snapchat, instagram, etc.) and how quickly they come and go. Communication research can barely keep up with the ongoing changes to human communication.

Researching something as complex as human communication can be an exercise in creativity, patience, and failure. Communication research, while relatively new in many respects, should follow several basic principles to be effective. Similar to other types of research, Communication research should be systematic, rational, self-correcting, self-reflexive, and creative to be of use (Babbie; Bronowski; Buddenbaum; Novak; Copi; Peirce; Reichenbach; Smith; Hughes & Hayhoe).

Seven Basic Steps of Research

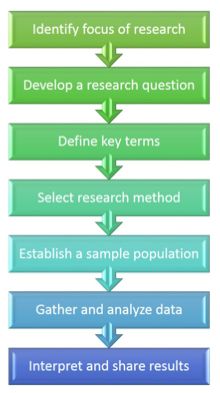

editWhile research can be messy, there are steps we can follow to avoid some of the pitfalls inherent with any research project. Research doesn’t always work out right, but we do use the following guidelines as a way to keep research focused, as well as detailing our methods so other can replicate them. Let’s look at seven basic steps that help us conduct effective research.

- Identify a focus of research. To conduct research, the first thing you must do is identify what aspect of human communication interests you and make that the focus of inquiry. Most Communication researchers examine things that interest them; such as communication phenomena that they have questions about and want answered. For example, you may be interested in studying conflict between romantic partners. When using a deductive approach to research, one begins by identifying a focus of research and then examining theories and previous research to begin developing and narrowing down a research question.

- Develop a research question(s). Simply having a focus of study is still too broad to conduct research, and would ultimately end up being an endless process of trial and error. Thus, it is essential to develop very specific research questions. Using our example above, what specific things would you want to know about conflict in romantic relationships? If you simply said you wanted to study conflict in romantic relationships, you would not have a solid focus and would spend a long time conducting your research with no results. However, you could ask, “Do couples use different types of conflict management strategies when they are first dating versus after being in a relationship for a while? It is essential to develop specific questions that guide what you research. It is also important to decide if an answer to your research question already exists somewhere in the plethora of research already conducted. A review of the literature available at your local library may help you decide if others have already asked and answered a similar question. Another convenient resource will be your university’s online database. This database will most likely provide you with resources of previous research through academic journal articles, books, catalogs, and various kinds of other literature and media.

- Define key terms. Using our example, how would you define the terms conflict, romantic relationship, dating, and long-term relationship? While these terms may seem like common sense, you would be surprised how many ways people can interpret the same terms and how particular definitions shape the research. Take the term long-term relationship, for example, what are all of the ways this can be defined? People married for 10 or more years? People living together for five or more years? Those who identify as being monogamous? It is important to consider populations who would be included and excluded from your study based on a particular definition and the resulting generalizability of your findings. Therefore, it is important to identify and set the parameters of what it is you are researching by defining what the key terms mean to you and your research. A research project must be fully operationalized, specifically describing how variables will be observed and measured. This will allow other researchers an opportunity to repeat the process in an attempt to replicate the results. Though more importantly, it will provide additional understanding and credibility to your research.

Communication Research Then |

- Select an appropriate research methodology. A methodology is the actual step-by-step process of conducting research. There are various methodologies available for researching communication. Some tend to work better than others for examining particular types of communication phenomena. In our example, would you interview couples, give them a survey, observe them, or conduct some type of experiment? Depending on what you wish to study, you will have to pick a process, or methodology, in order to study it. We’ll discuss examples of methodologies later in this chapter.

- Establish a sample population or data set. It is important to decide who and what you want to study. One criticism of current Communication research is that it often relies on college students enrolled in Communication classes as the sample population. This is an example of convenience sampling. Charles Teddlie and Fen Yu write, “Convenience sampling involves drawing samples that are both easily accessible and willing to participate in a study” (78). One joke in our field is that we know more about college students than anyone else. In all seriousness, it is important that you pick samples that are truly representative of what and who you want to research. If you are concerned about how long-term romantic couples engage in conflict, (remember what we said about definitions) college students may not be the best sample population. Instead, college students might be a good population for examining how romantic couples engage in conflict in the early stages of dating.

Communication Research Now |

- Gather and analyze data. Once you have a research focus, research question(s), key terms, a method, and a sample population, you are ready to gather the actual data that will show you what it is you want to answer in your research question(s). If you have ever filled out a survey in one of your classes, you have helped a researcher gather data to be analyzed in order to answer research questions. The actual “doing” of your methodology will allow you to collect the data you need to know about how romantic couples engage in conflict. For example, one approach to using a survey to collect data is to consider adapting a questionnaire that is already developed. Communication Research Measures II: A Sourcebook is a good resource to find valid instruments for measuring many different aspects of human communication (Rubin et al.).

- Interpret and share results. Simply collecting data does not mean that your research project is complete. Remember, our research leads us to develop and refine theories so we have more sophisticated representations about how our world works. Thus, researchers must interpret the data to see if it tells us anything of significance about how we communicate. If so, we share our research findings to further the body of knowledge we have about human communication. Imagine you completed your study about conflict and romantic couples. Others who are interested in this topic would probably want to see what you discovered in order to help them in their research. Likewise, couples might want to know what you have found in order to help themselves deal with conflict better.

Communication Research and You |

Although these seven steps seem pretty clear on paper, research is rarely that simple. For example, a master’s student conducted research for their Master’s thesis on issues of privacy, ownership and free speech as it relates to using email at work. The last step before obtaining their Master’s degree was to share the results with a committee of professors. The professors began debating the merits of the research findings. Two of the three professors felt that the research had not actually answered the research questions and suggested that the master's candidate rewrite their two chapters of conclusions. The third professor argued that the author HAD actually answered the research questions, and suggested that an alternative to completely rewriting two chapters would be to rewrite the research questions to more accurately reflect the original intention of the study. This real example demonstrates the reality that, despite trying to account for everything by following the basic steps of research, research is always open to change and modification, even toward the end of the process.

Motivational Factors for Research

editWe think it is important to discuss the fact that human nature influences all research. While some researchers might argue that their research is objective, realistically, no research is totally objective. What does this mean? Researchers have to make choices about what to research, how they will conduct their research, who will pay for their research, and how they will present their research conclusions to others. These choices are influenced by the motives and material resources of researchers. The most obvious case of this in the physical sciences is research sponsored by the tobacco industry that downplays the health hazards associated with smoking (Frisbee & Donley). Intuitively, we know that certain motivations influence this line of research as it is an example of an extreme case of motivational factors influencing research. Realistically though, all researchers are motivated by certain factors that influence their research.

We will highlight three factors that motivate the choices we make when conducting communication research: 1) The intended outcomes, 2) theoretical preferences, and 3) methodological preferences.

Intended Outcomes

editCase In Point |

One question researchers ask while doing their research project is, “What do I want to accomplish with this research?” Three primary research goals are to increase understanding of a behavior or phenomenon, predict behavior, or create social change..

A great deal of Communication research seeks understanding as the intended outcome of the research. As we gain greater understanding of human communication we are able to develop more sophisticated theories to help us understand how and why people communicate. One example might be research investigates the communication of registered nurses to understand how they use language to define and enact their professional responsibilities. Research has discovered that nurses routinely refer to themselves as “patient advocates” and state that their profession is unique, valuable, and distinct from being an assistant to physicians. Having this understanding can be useful for enacting change by educating physicians and nurses about the impacts of their language choices in health care.

A second intended outcome of Communication research is prediction and control. Ideas of prediction and control are taken from the physical sciences (remember our discussion of Empirical Laws theories in the last chapter?). Many Communication researchers want to use the results of their research to predict and control communication in certain contexts. This type of research can help us make communicative choices from an informed perspective. In fact, when you communicate, you often do so with the intention of prediction and control. Imagine walking on campus and seeing someone you would like to ask out. Because of your past experiences, you predict that if you say certain things to them in a certain way, you might have a greater likelihood that they will respond positively. Your predictions guide your behaviors in order to control the exchange at some level. This same idea motivates many Communication researchers to approach their research with the intention of being able to predict and control communication contexts. For example, in the article The Fear of Public Speaking, Sian Beilock, Ph.D explains prediction and control in action.

A third intended outcome of Communication research is positive critical/cultural change in the world. Scholars often perform research in order to challenge communicative norms and effect cultural and societal change. Research that examines health communication campaigns, for example, seeks to understand how effective campaigns are in changing our health behaviors such as using condoms to prevent sexually transmitted diseases or avoiding high fat foods. When it is determined that health campaigns are ineffective, researchers often suggest changes to health communication campaigns to increase their efficacy in reaching the people who need access to the information (Stephenson & Southwell).

As humans, researchers have particular goals in mind. Having an understanding of what they want to accomplish with their research helps them formulate questions and develop appropriate methodologies for conducting research that will help them achieve their intended outcomes.

Theoretical Preferences

editRemember that theoretical paradigms offer different ways to understand communication. While it is possible to examine communication from multiple theoretical perspectives, it has been our experience that our colleagues tend to favor certain theoretical paradigms over others. Put another way, we all understand the world in ways that make sense to us.

Which theoretical paradigm(s) do you most align yourself with? How would this influence what you would want to accomplish if you were researching human communication? What types of communication phenomena grab your attention? Why? These are questions that researchers wrestle with as they put together their research projects.

Methodological Preferences

editAs you’ve learned, the actual process of doing research is called the methodology. While most researchers have preferences for certain theoretical paradigms, most researchers also have preferred methodologies for conducting research in which they develop increased expertise throughout their careers. As with theories, there are a large number of methodologies available for conducting research. As we did with theories, we believe it is easier for you to understand methodologies by categorizing them into paradigms. Most Communication researchers have a preference for one research paradigm over the others. For our purposes, we have divided methodological paradigms into 1) rhetorical methodologies, 2) quantitative methodologies, and 3) qualitative methodologies.

Rhetorical Methodologies

editWe encode and decode messages everyday. As we take in messages, we use a number of criteria to evaluate them. We may ask, “Was the message good, bad, or both?” “Was it effective or ineffective?” “Did it achieve its intended outcome?” “How should I respond to the message?” Think about the last movie you watched. Did you have a conversation about the movie with others? Did that conversation include commentary on various parts of the film such as the set design, dialogue, plot, and character development? If so, you already have a taste of the variety of elements that go into rhetorical research. Simply stated, rhetorical methods of research are sophisticated and refined ways to evaluate messages. Foss explains that we use rhetorical approaches as a way “of systematically investigating and explaining symbolic acts and artifacts for the purpose of understanding rhetorical processes" (6).

Steps for Doing Rhetorical Research |

Types of Methods for Rhetorical Criticism

editWhat do rhetorical methods actually look like? How are they done? While each rhetorical methodology acts as a unique lens for understanding messages, no one is more correct over another. Instead, each allows us a different way for understanding messages and their effects. Let’s examine a few of the more common rhetorical methodologies including, 1) Neo-Aristotelian, 2) Fantasy-Theme, 3) Narrative, 4) Pentadic, 5) Feminist, and 6) Ideological.

- Neo-Aristotelian Criticism. In Chapter 2 you learned quite a bit about the rhetorical roots of our field, including a few of the contributions of Aristotle. The neo-Aristotelian method uses Aristotle’s ideas to evaluate rhetorical acts. First, a researcher recreates the context for others by describing the historical period of the message being studied. Messages are typically speeches or other forms of oral rhetoric as this was the primary focus of rhetoric during the Classical Period. Second, the researcher evaluates the message using the canons of rhetoric. For example, the researcher may examine what types of logic are offered in a speech or how its delivery enhances or detracts from the ethos of the speaker. Finally, the researcher assesses the effectiveness of the message given its context and its use of the canons.

- Fantasy Theme Criticism. Fantasy Theme analysis is a more contemporary rhetorical method credited to Ernest G. Bormann (1972; 1985; 1990; 2000; Cooren et al.). The focus of this methodology is on groups rather than individuals, and is particularly well-suited for analyzing group messages that come from social movements, political campaigns, or organizational communication. Essentially, a fantasy is a playful way of interpreting an experience (Foss). Fantasy theme research looks for words or phrases that characterize the shared vision of a group in order to explain how the group characterizes or understands events around them. Fantasy theme analysis offers names and meaning to a group’s experience and presents outsiders with a frame for interpreting the group’s rhetorical response.

- Narrative Criticism. Much of what you learned as a child was probably conveyed to you through stories (bedtime stories, fables, and fairy tales) that taught you about gender roles, social roles, ethics, etc. Fairy tales, for example, teach us that women are valued for their youth and beauty and that men are valued when they are strong, handsome, smart, and riding a white horse! Other stories you remember may be more personal, as in the telling of your family’s immigration to the United States and the values learned from that experience. Whatever the case, narrative rhetorical research contends that people learn through the sharing of stories. A researcher using this method examines narratives and their component parts—the plot, characters, and settings—to better understand the people (culture, groups, etc.) telling these stories. This research approach also focuses on the effects of repeating narratives. Think about Hollywood romantic comedies such as When Harry Met Sally, Silver Lining Playbook, Knocked Up, and Bridesmaids. When you see one of these movies, does it feel like you’ve seen it before? For example, For example, these movies use usually have a confused character and some conflict that ends in a perfect relationship. Why does Hollywood do this? What is the purpose and/or effect of retelling these story lines over and over again? These are some of the concerns of researchers who use narrative analysis to research rhetorical acts.

- Pentadic Criticism. Kenneth Burke developed the idea of the pentad using the metaphor of drama. As in a dramatic play, the pentad contains five elements—the act, agent, agency, scene, and purpose. The act tells what happened, the agent is who performed the act, agency includes the tools/means the agent used to perform the act, the scene provides the context for the act, and the purpose explains why the act occurred. By using the elements of the pentad to answer questions of who, what, when, where, and why, a rhetorical researcher may uncover a communicator’s motives for her or his rhetorical actions. Click this link to watch a visual representation of Kenneth Burke’s dramatistic pentad.

- Feminist Criticism. Most feminist perspectives share the basic assumptions that women are routinely oppressed by patriarchy, women’s experiences are different then men’s, and women’s perspectives are not equally incorporated into our culture (Foss). We can use feminist rhetorical research to help us determine the degree to which women’s perspectives are both absent and/or discredited in rhetorical acts. Thus, feminist rhetorical research, “is the analysis of rhetoric to discover how the rhetorical construction of gender is used as a means for oppression and how that process can be challenged and resisted” (Foss, 168). Although many think of “women” in reference to feminism, it is important to note that many men consider themselves feminists and that feminism is concerned with oppression of all forms—race, class, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, and gender.

Case In Point |

- Ideological Criticism. Ideology is a collection of values, beliefs, or ethics that influence modes of behavior for a group or culture. Rhetorical scholars interested in understanding a culture’s values often use ideological methods. Ideologies are complex and multifaceted, and ideological methods draw from diverse schools of thought such as Marxism, feminism, structuralism, deconstructionism, and postmodernism. This research often uncovers assumptions and biases in our language that provide insight into how dominant groups and systems are maintained rhetorically, and how they can be challenged and transformed through rhetoric. Artifacts of popular culture such as movies, television shows, etc. are often the focus of this research as they are the sites at which struggles about meanings occur in the popular culture.

Outcomes of Rhetorical Methodologies

editWhat is the value of researching acts of communication from a rhetorical perspective? The systematic research of messages tells us a great deal about the ways people communicate, the contexts in which they communicate, the effects of communication in particular contexts, and potential areas to challenge and transform messages to create social change.

Rhetorical research methodologies help us better determine how and why messages are effective or ineffective, as well as the outcomes of messages on audiences. Think about advertising campaigns. Advertising agencies spend millions of dollars evaluating the effectiveness of their messages on audiences. The purpose of advertising is to persuade us to act in some way, usually the purchasing of products or services. Advertisers not only evaluate the effectiveness of their messages by determining the amount of products sold, they also evaluate effectiveness by looking at audience response to the messages within the current cultural and social contexts.

Quantitative Methods

editSteps for Doing Quantitative Research |

The term quantitative refers to research in which we can quantify, or count, communication phenomena. Quantitative methodologies draw heavily from research methods in the physical sciences explore human communication phenomena through the collection and analysis of numerical data. Let’s look at a simple example. What if we wanted to see how public speaking textbooks represent diversity in their photographs and examples. One thing we could do is quantify these to come to conclusions about these representations. For quantitative research, we must determine which communicative acts to count? How do we go about counting them? Is there any human communicative behavior that would return a 100% response rate like the effects of gravity in the physical sciences? What can we learn by counting acts of human communication?

Suppose you want to determine what communicative actions illicit negative responses from your professors. How would you go about researching this? What data would you count? In what ways would you count them? Who would you study? How would you know if you discovered anything of significance that would tell us something important about this? These are tough questions for researchers to answer, particularly in light of the fact that, unlike laws in the physical sciences, human communication is varied and unpredictable.

Nevertheless, there are several quantitative methods researchers use to study communication in order to reveal patterns that help us predict and control our communication. Think about polls that provide feedback for politicians. While people do not all think the same, this type of research provides patterns of thought to politicians who can use this information to make policy decisions that impact our lives. Let’s look at a few of the more frequent quantitative methods of communication research.

Types of Quantitative Methods

editThere are many ways researchers can quantify human communication. Not all communication is easily quantified, but much of what we know about human communication comes from quantitative research.

- Experimental Research is the most well-established quantitative methodology in both the physical and social sciences. This approach uses the principles of research in the physical sciences to conduct experiments that explore human behavior. Researchers choose whether they will conduct their experiments in lab settings or real-world settings. Experimental research generally includes a control group (the group where variables are not altered) and the experimental group(s) (the group in which variables are altered). The groups are then carefully monitored to see if they enact different reactions to different variables.

To determine if students were more motivated to learn by participating in a classroom game versus attending a classroom lecture, the researchers designed an experiment. They wanted to test the hypothesis that students would actually be more motivated to learn from the game. Their next question was, “do students actually learn more by participating in games?” In order to find out the answers to these questions they conducted the following experiment. In a number of classes instructors were asked to proceed with their normal lecture over certain content (control group), and in a number of other classes, instructors used a game that was developed to teach the same content (experimental group). The students were issued a test at the end of the semester to see which group did better in retaining information, and to find out which method most motivated students to want to learn the material. It was determined that students were more motivated to learn by participating in the game, which proved the hypothesis. The other thing that stood out was that students who participated in the game actually remembered more of the content at the end of the semester than those who listened to a lecture. You might have hypothesized these conclusions yourself, but until research is done, our assumptions are just that (Hunt, Lippert & Paynton).

Case In Point |

- Survey Research is used to ask people a number of questions about particular topics. Surveys can be online, mailed, handed out, or conducted in interview format. After researchers have collected survey data, they represent participants’ responses in numerical form using tables, graphs, charts, and/or percentages. On our campus, anonymous survey research was done to determine the drinking and drug habits of our students. This research demonstrated that the percentage of students who frequently use alcohol or drugs is actually much lower than what most students think. The results of this research are now used to educate students that not everyone engages in heavy drinking or drug use, and to encourage students to more closely align their behaviors with what actually occurs on campus, not with what students perceive happens on campus. It is important to remember that there is a possibility that people do not always tell the truth when they answer survey questions. We won’t go into great detail here due to time, but there are sophisticated statistical analyses that can account for this to develop an accurate representation of survey responses.

- Content Analysis. Researchers use content analysis to count the number of occurrences of their particular focus of inquiry. Communication researchers often conduct content analyses of movies, commercials, television shows, magazines, etc., to count the number of occurrences of particular phenomena in these contexts to explore potential effects. Harmon, for example, used content analysis in order to demonstrate how the portrayal of blackness had changed within Black Entertainment Television (BET). She did this by observing the five most frequently played films from the time the cable network was being run by a black owner, to the five most frequently played films after being sold to white-owned Viacom, Inc. She found that the portrayal, context and power of the black man changes when a white man versus a black man is defining it. Content analysis is extremely effective for demonstrating patterns and trends in various communication contexts. If you would like to do a simple content analysis, count the number of times different people are represented in photos in your textbooks. Are there more men than women? Are there more caucasians represented than other groups? What do the numbers tell you about how we represent different people?

- Meta-Analysis. Do you ever get frustrated when you hear about one research project that says a particular food is good for your health, and then some time later, you hear about another research project that says the opposite? Meta-analysis analyzes existing statistics found in a collection of quantitative research to demonstrate patterns in a particular line of research over time. Meta-analysis is research that seeks to combine the results of a series of past studies to see if their results are similar, or to determine if they show us any new information when they are looked at in totality. The article, Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis examined past research regarding narratives and their persuasiveness in health care settings. The meta-analysis revealed that in-person and video narratives had the most persuasive impacts while written narratives had the least (Shen, Sheer, Li).

Outcomes of Quantitative Methodologies

editBecause it is unlikely that Communication research will yield 100% certainty regarding communicative behavior, why do Communication researchers use quantitative approaches? First, the broader U.S. culture values the ideals of quantitative science as a means of learning about and representing our world. To this end, many Communication researchers emulate research methodologies of the physical sciences to study human communication phenomena. Second, you’ll recall that researchers have certain theoretical and methodological preferences that motivate their research choices. Those who understand the world from an Empirical Laws and/or Human Rules Paradigm tend to favor research methods that test communicative laws and rules in quantitative ways.

Even though Communication research cannot produce results with 100% accuracy, quantitative research demonstrates patterns of human communication. In fact, many of your own interactions are based on a loose system of quantifying behavior. Think about how you and your classmates sit in your classrooms. Most students sit in the same seats every class meeting, even if there is not assigned seating. In this context, it would be easy for you to count how many students sit in the same seat, and what percentage of the time they do this. You probably already recognize this pattern without having to do a formal study. However, if you wanted to truly demonstrate that students communicatively manifest territoriality to their peers, it would be relatively simple to conduct a quantitative study of this phenomenon. After completing your research, you could report that X% of students sat in particular seats X% of times. This research would not only provide us with an understanding of a particular communicative pattern of students, it would also give us the ability to predict, to a certain degree, their future behaviors surrounding space issues in the classroom.

Quantitative research is also valuable for helping us determine similarities and/or differences among groups of people or communicative events. Representative examples of research in the areas of gender and communication (Berger; Slater), culture and communication (McCann, Ota, Giles, & Caraker; Hylmo & Buzzanell), as well as ethnicity and communication (Jiang Bresnahan, Ohashi, Nebashi, Wen Ying, Shearman; Murray-Johnson) use quantitative methodologies to determine trends and patterns of communicative behavior for various groups. While these trends and patterns cannot be applied to all people, in all contexts, at all times, they help us understand what variables play a role in influencing the ways we communicate.

While quantitative methods can show us numerical patterns, what about our personal lived experiences? How do we go about researching them, and what can they tell us about the ways we communicate? Qualitative methods have been established to get at the “essence” of our lived experiences, as we subjectively understand them.

Qualitative Methods

editQualitative research methodologies draw much of their approach from the social sciences, particularly the fields of Anthropology, Sociology, and Social-Psychology. If you’ve ever wished you could truly capture and describe the essence of an experience you have had, you understand the goal of qualitative research methods. Rather than statistically analyzing data, or evaluating and critiquing messages, qualitative researchers are interested in understanding the subjective lived-experience of those they study. In other words, how can we come to a more rich understanding of how people communicate?

In an attempt to define qualitative methods Thomas Lindlof states that qualitative research examines the “form and content of human behavior…to analyze its qualities, rather than subject it to mathematical or other formal transformations” (21). Anderson and Meyer state that qualitative methods, “do not rest their evidence on the logic of mathematics, the principle of numbers, or the methods of statistical analysis” (247). Dabbs says that qualitative research looks at the quality of phenomena while quantitative methods measure quantities and/or amounts. In qualitative research researchers are interested in the, “what, how, when, and where of a thing….[looking for] the meanings, concepts, definitions, characteristics, metaphors, symbols, and descriptions of things” (Berg 2-3). Data collection comes in the form of words or pictures (Neuman 28). As Kaplan provides a very simple way of defining qualitative research when he says, “if you can measure it, that ain’t it” (206).

Types of Qualitative Methods

editWhile qualitative research sounds simple, it can be a “messy” process because things do not always go as planned. One way to make qualitative research “cleaner” is to be familiar with, and follow, the various established qualitative methods available for studying human communication.

- Ethnography. Ethnography is arguably the most recognized and common method of qualitative research in Communication. Ethnography “places researchers in the midst of whatever it is they study. From this vantage, researchers can examine various phenomena as perceived by participants and represent these observations” to others (Berg 148). Ethnographers try to understand the communicative acts of people as they occur in their actual communicative environments. One way to think of this is the idea of learning about a new culture by immersing oneself in that culture. While there are many strategies for conducting ethnography, the idea is that a researcher must enter the environment of those under study to observe and understand their communication.

- Focus Group Interviewing. Researchers who use focus group interviewing meet with groups of people to understand their communication characteristics. (Berg). These interviews foster an environment for participants to discuss particular topics of interest to the group and/or researcher. While we are all familiar with the numbers that we encounter in political polls, every so often television news organizations will conduct focus group interviews to find out how particular groups actually feel about, and experience, the political process as a citizen. This is an applied version of focus group research techniques and provides insight into the ways various groups understand and enact their realities.

- Action Research. A qualitative method whose intended outcome is social change is action research. Action research seeks to create positive social change through “a highly reflective, experiential, and participatory mode of research in which all individuals involved in the study, researcher and subject alike, are deliberate and contributing actors in the research enterprise” (Berg 196; Wadsworth). The goal of action research is to provide information that is useful to a particular group of people that will empower the members of that group to create change as a result of the research (Berg). An example of action research might be when researchers study the teaching strategies of teachers in the classroom. Typically, teachers involve themselves in the research and then use the findings to improve their teaching methods. If you’ve ever had a professor who had unique styles of teaching, it is likely that he/she may have been involved in research that examined new approaches to teaching students.

- Unobtrusive Research. Another method for conducting qualitative research is unobtrusive research. As Berg points out, “to some extent, all the unobtrusive strategies amount to examining and assessing human traces” (209). We can learn a great deal about the behavior of others by examining the traces humans leave behind as they live their lives. In a research class offered at our university, for instance, students investigated the content of graffiti written in university bathrooms. Because our campus has an environmentally conscious culture, much of the graffiti in bathrooms reflects this culture with slogans written on paper towel dispensers that read, “Paper towels=trees.” The students who conducted this research were using unobtrusive strategies to determine dimensions of student culture in the graffiti that was left behind in bathrooms.

- Historiography. Historiography is a method of qualitative research “for discovering, from records and accounts, what happened during some past period” (Berg 233). Rather than simply putting together a series of facts, research from this perspective seeks to gain an understanding of the communication in a past social group or context. For example, the timelines in the history chapter of this text are an attempt to chronologically put together the story of the discipline of Communication. While there is no “true” story, your authors have tried to piece together, from their own research, the important pieces that make up what we believe is the story of the formation of Communication study.

- Case Studies. Case studies involve gathering significant information about particular people, contexts, or phenomena to understand a particular case under investigation. This approach uses many methods for data collection but focuses on a particular case to gain “holistic description and explanation” (Berg 251). Those who use case study approaches may look at organizations, groups within those organizations, specific people, etc. The idea is to gain a broad understanding of the phenomena and draw conclusions from them. For example, a case study may examine a specific teaching method as a possible solution to increase graduation rates while improving student information retention (Foss et al.). Examining specific cases may help some teachers rethink their current teaching method and offer some alternatives to the standardized teaching paradigms.

While there are other qualitative research methodologies, the methods one chooses to examine communication are most often decided by the researcher’s intended outcomes, resources available, and the research question(s) of focus. There are no hard rules for qualitative research. Instead, researchers must make many choices as they engage in this process.

Outcomes of Qualitative Methodologies

editCommunication Research and You |

What can we learn by using qualitative research methods for studying communication? Qualitative Communication researchers often believe that quantitative methods do not capture the essence of our lived experience. In other words, it is difficult to quantify everything about our lives and therefore, we need different strategies for understanding our world. Think of the various ways you experience and communicate in your relationships? It’s highly unlikely that you spend the bulk of your communication quantifying your daily experiences. However, through methods like observation, interviewing, journaling, etc., we might be able to get a better understanding of the ways people experience and communicate their feelings.

Another value of qualitative research is that it resonates with readers who are able to identify with the lived-experiences represented in the research (Neuman). Statistical studies often seem detached from how we experience life. However, qualitative studies contain “rich description, colorful detail, and unusual characters; they give the reader a feel for social settings (Neuman 317). This rich description allows us to identify with the communication experiences of others, and learn through this identification.

Over the years, female scholars have demonstrated a greater frequency in the use of qualitative approaches (Grant, Ward & Rong; Ward & Grant), producing significant contributions to our understanding of human communication using these methods. From understanding to social change, feminist scholars demonstrate the importance of qualitative inquiry for strengthening the body of scholarship in our discipline. While researchers who use quantitative approaches tend to value prediction and control as potential outcomes of their research, those who use qualitative approaches seek greater understanding of human communication phenomena, or evaluate current pragmatic uses of human communication to help identify and change oppressive power structures.

Summary

editCommunication research is important because it focuses on a common goal—to enhance our interactions with others. In this chapter we highlighted how research is done and the basic steps that guide most research projects—identify the topic, write a research question, define key terms, select a methodology, establish a sample, gather and analyze the data, and finally, interpret and share the results. When conducting research, three factors motivate the choices we make: our intended outcomes, theoretical preferences, and methodological preferences. Depending on these factors, research may lead us to greater understanding, allow us to predict or control a communication situation, or create cultural change.

Conceptualizing Communication research can be done more easily by understanding the three broad methodological approaches/paradigms for conducting Communication research: Rhetorical Methodologies, Quantitative Methodologies, and Qualitative Methodologies. The rhetorical approach evaluates messages in various contexts such as political discourse, art, and popular culture. A variety of methods are available such as neo-aristotelian, fantasy theme, narrative, pentadic, feminist, and ideological criticism. Quantitative methods are characterized by counting phenomena and are useful for predicting communication outcomes or comparing cultures and populations. They include experimental research, surveys, content analysis, and meta-analysis. Qualitative methods offer the opportunity to understand human communication as it occurs in a “natural” context rather than a laboratory setting. This is accomplished through ethnography, focus groups, action research, unobtrusive research, historiography, and case studies. While these approaches share similarities, their focus and specific methods are quite different and produce different outcomes. No research methodology or method is better than another. Instead, approaches to Communication research simply reveal different aspects of human communication in action.

Discussion Questions

edit- If you were going to conduct communication research, what topic(s) would be most interesting to you? What specific questions would you want to ask and answer? How would you go about doing this?

- Of the three broad research methodologies, do you find yourself having a preference for one of them? If so, what specific type of research method would you want to use within the area you have a preference for?

- If you were going to conduct research, what outcome would you want to gain from your research? Are you more interested in understanding, prediction/control, or creating social change? What is the value of each of these approaches?

Key Terms

edit- action research

- case studies

- content analysis

- continuum of intended outcomes

- control group

- critical/cultural change

- ethnography

- data

- experimental group

- experimental research

- fantasy theme

- feminist

- focus group interviewing

- historiography

- ideological

- key terms

- meta-analysis

- methodological preferences

- methodology

- narrative

- neo-Aristotelian

- pentadic

- prediction/control

- qualitative methodologies

- quantitative methodologies

- research

- research focus

- research questions

- rhetorical methodologies

- sample

- survey research

- theoretical preferences

- understanding

- unobtrusive research

References

editAnderson, James, and Timothy Meyer. Mediated Communication : A Social Action Perspective (Current Communication). {SAGE Publications}, 1988. CiteULike. Web. 11 Oct. 2014.

Babbie, Earl R. Survey Research Methods. Wadsworth Pub. Co., 1973. Print.

Barry, Christine A. “Multiple Realities in a Study of Medical Consultations.” Qualitative Health Research 12.8 (2002): 1093–1111. qhr.sagepub.com. Web.

Beilock, Sian Ph.D.“The Fear of Public Speaking.” N.p., n.d. (2012). Web. 10 Dec. 2014.

Berg, Bruce Lawrence, and Howard Lune. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Vol. 5. Pearson Boston, 2004. Google Scholar. Web.

Berger, Charles R. “Effects of Discounting Cues and Gender on Apprehension Quantitative Versus Verbal Depictions of Threatening Trends.” Communication Research 30.3 (2003): 251–271. crx.sagepub.com. Web.

Bormann, Ernest G. “Fantasy and Rhetorical Vision: The Rhetorical Criticism of Social Reality.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 58.4 (1972): 396–407. Print.

---Small Group Communication: Theory and Practice. Harper & Row, 1990. Print.

---The Force of Fantasy : Restoring the American Dream. Carbondale; Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

---The Force of Fantasy: Restoring the American Dream. SIU Press, 2000. Print.

Bormann, Ernest, and Nancy Bormann. Speech Communication : An Interpersonal Approach. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Bresnahan, Mary Jiang et al. “Attitudinal and Affective Response toward Accented English.” Language & Communication 22.2 (2002): 171–185. ScienceDirect. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Bronowski, Jacob. Science and Human Values. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.

Brown, Stephen Howard. “Jefferson’s First Declaration of Independence: A Summary View of the Rights of British America Revisited.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 89.3 (2003): 235–252. Print.

Buddenbaum, Judith, Ph D. Applied Communication Research. Blackwell Publishing, 2001. Print.

Buirski, Lindie. “Climate Change and Drama: The Youth Learning About and Responding to Climate Change Issues Through Drama.” Global Media Journal: African Edition 7.1 (2013): 40–46. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. University of California Press, 1969. Print.

---Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. University of California Press, 1966. Print.

---The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action. University of California Press, 1974. Print.

"Communications." Michigan Academician 41.2 (2013): 1302. ProQuest. Web. 13 Oct. 2014.

Cooren, François et al. Language and Communication at Work: Discourse, Narrativity, and Organizing. Oxford University Press, 2014. Print.

Copi, Irving M. Introduction to Logic. Third edition. Macmillan, 1968. Print.

Dabbs Jr, James M. “Making Things Visible.” Varieties of qualitative research (1982): 31–63. Print.

DiMatteo, M.Robin et al. “Correspondence Among Patients’ SelfReports, Chart Records, and Audio/Videotapes of Medical Visits.” Health Communication 15.4 (2003): 393. Print.

Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. “Association of Allcause Mortality with Overweight and Obesity Using Standard Body Mass Index Categories. A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis." British Dental Journal, 214.3 (2013): 113.

Foss, Karen A. et al. “Increasing College Retention with a Personalized System of Instruction: A Case Study.” Journal of Case Studies in Education 5 (2014): 1–20. Print.

Foss, Sonja K. Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration & Practice (3rd ed.). Waveland Press Prospect Heights, IL, 2004. Print.

Foss, Karen A., Sonja K. Foss, and Cindy L. Griffin. Feminist Rhetorical Theories. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Pub., 1999. Print.

Frisbee, Stephanie J., and Donley T. Studlar. "LOCAL TOBACCO CONTROL COALITIONS IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA: CONTAGION ACROSS THE BORDER?." (2011).

"Graduate Program." Communication Technology Research. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Dec. 2014. <http://commstudies.utexas.edu/research/communicationtechnologyresearch>.

Grant, Linda, Kathryn B. Ward, and Xue Lan Rong. “Is There An Association between Gender and Methods in Sociological Research?” American Sociological Review 52.6 (1987): 856–862. JSTOR. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Hall, J. A., and R. Rosenthal. "Interpreting and Evaluating MetaAnalysis." Evaluation & the Health Professions 18.4 (1995): 393407. Web.

Harmon, Molly. "Broadcasting Blackness: A Content Analysis of Movies Aired by Black Entertainment Television (BET) Before and After Viacom’s Ownership." (2012): 125.

Web. 4 Dec. 2014. <https://www.saintmarys.edu/files/Harmon%20Pap_0.pdf>.

Hughes, Michael A., and George F. Hayhoe. A Research Primer for Technical Communication: Methods, Exemplars, and Analyses. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Hunt, S., Lippert, L., & Paynton, S. (1998). "Alternatives to traditional instruction: Using games and simulations to increase student learning." Communication Research Reports, 15(1), 3644.

Hylmö, Annika, and Patrice Buzzanell. “Telecommuting as Viewed through Cultural Lenses: An Empirical Investigation of the Discourses of Utopia, Identity, and Mystery.” Communication Monographs 69.4 (2002): 329–356. Taylor and Francis+NEJM. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Kamhawi, Rasha, and David Weaver. “Mass Communication Research Trends from 1980 to 1990.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80.1 (2003): 727. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Kaplan, Abraham. The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1998. Print.

Lindlof, Thomas R., and Bryan C. Taylor. Qualitative Communication Research Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011. Print.

McCann, Robert, Ota, H., Giles, H., & Caraker, R. (2003). "Accommodation and nonaccommodation across the lifespan: Perspectives from Thailand, Japan, and the United States of America." Communication Reports, 16(2), 6992.

Murray-Johnson, Lisa, Sampson, Joe, Kim Witte, Kelly Morrison, WenYing Liu, Anne P. Hubbell. “Addressing Cultural Orientations in Fear Appeals: Promoting AIDSProtective Behaviors among Mexican Immigrant and African American Adolescents and American and Taiwanese College Students.” Journal of Health Communication 6.4 (2001): 335–358. Taylor and Francis+NEJM. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Neuman, W. Russell et al. “The Seven Deadly Sins of Communication Research.” Journal of Communication 58.2 (2008): 220–237. EBSCOhost. Web. 5 Oct. 2014.

Neuman, William Lawrence. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 7th ed. N.p.: Pearson, 2010. Print.

Novak, Katherine Ph D. Applied Communication Research. Blackwell Publishing, 2001. Print.

Peirce, Charles S. Essays in the Philosophy of Science. (1957): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Reichenbach, Hans. “Experience and Prediction: An Analysis of the Foundations and the Structure of Knowledge.” (1938): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Rubin, Rebecca B. et al. Communication Research Measures II: A Sourcebook. Routledge, 2010. Google Scholar. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Shen, Fuyuan, Vivian C. Sheer, and Ruobing Li. “Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Advertising 44.2 (2015): 105–113. EBSCOhost. Web.

Slater, Michael D. “Alienation, Aggression, and Sensation Seeking as Predictors of Adolescent Use of Violent Film, Computer, and Website Content.” Journal of Communication 53.1 (2003): 105–121. Wiley Online Library. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Smith, Bruce Lannes, Harold D. Lasswell, and Ralph D. Casey. Propaganda, Communication, and Public Opinion. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1946. Print.

Smith, Mary John. Contemporary Communication Research Methods. Wadsworth Publishing Company Belmont, CA, 1988. Print.

Stanaitis, Sarunas. "Intervehicle Communication Research Communication Scenarios." Mokslas : Lietuvos Ateitis, 2.1 (2010): 77.

Stephenson, Michael T., and Brian G. Southwell. “Sensation Seeking, the Activation Model, and Mass Media Health Campaigns: Current Findings and Future Directions for Cancer Communication.” Journal of Communication 56 (2006): S38–S56. Wiley Online Library. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Stephenson, Michael T. “Examining Adolescents’ Responses to Antimarijuana PSAs.” Human Communication Research 29.3 (2003): 343–369. Wiley Online Library. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Stevenson, Seth. “Aliens Don’t Do Drugs.” Slate 18 June 2007. Slate. Web.

Tankard Jr, James W. "Wilbur Schramm: Definer of a Field." Journalism Educator 43.3 (1988): 11-16.

Teddlie, Charles, and Fen Yu. “Mixed Methods Sampling a Typology with Examples.” Journal of mixed methods research 1.1 (2007): 77–100. Print.

Tenore, Mallary Jean. “10 Rhetorical Strategies That Made Bill Clinton’s DNC Speech Effective.” N.p., 6 Sept. 2012. Web. 11 Aug. 2015.

Ward, Kathryn B., and Linda Grant. “The Feminist Critique and a Decade of Published Research in Sociology Journals.” Sociological Quarterly 26.2 (1985): 139–157. Wiley Online Library. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

Wadsworth, Yoland. What is participatory action research? Action Research International. 1998.

“Which Conflicts Consume Couples the Most?" This Emotional Life N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Aug. 2015.

Zabava Ford, Wendy S. “Communication Practices of Professional Service Providers: Predicting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 31.3 (2003): 189–211. Taylor and Francis+NEJM. Web. 12 Oct. 2014.