Professionalism/Moonlighting

moonlighting. n.

...

3. colloq. (orig. U.S.). The practice of doing paid work in addition to one's regular employment.[1]

In American usage, moonlighting can refer to a high school music teacher who gives private lessons, a doctor who takes on shifts at multiple locations, or a software developer who spends after-work hours on a startup. In some cases, moonlighters seek extra income. Others moonlight for professional and personal development. Some moonlight as an opportunity for innovation and to experiment with new ideas.

For some, moonlighting is necessary, and even admirable. However, when professionals undertake additional work as professionals, they encounter ethical and legal risks. Employees may encounter a conflict of interest, if their 'moonlighting' activities conflict with the goals of their employer, or if moonlighting influences their performance. Some employment contracts have moonlighting clauses. These clauses vary, some restricting employees from secondary employment and others claiming ownership of intellectual property.

Theoretical Background

editLegal Responsibilities

editMoonlighting has many professional implications as it can affect an employee's performance, it can cause safety and legal issues, and it can result in conflicts of interest. Professionals have two primary legal obligations in their field: duty of care and duty of loyalty. Moonlighting can put these responsibilities in jeopardy.

Duty of Care

editFirst, duty of care is a legal obligation to safely perform duties in order to avoid harm.[2] In other words, professionals must act with care. For example, a professional operating heavy machinery or flying an airplane has an obvious obligation, both moral and legal, to concentrate on their work and do it well. An area where this obligation clashes with reality is in medical practice, particularly for those doctors who are in their residencies. At that point in a doctor's life, there's a strong motivation to get more experience and to pay back school debt, both of which can be done by working more hours.[3] Thus, residents commonly work extra shifts or even a second job in addition to their already rigorous residency.[4] Unsurprisingly, this leads to sleep deprivation, which effects quality of work. This was confirmed by a significant study revealing an increased number of errors made in an ICU due to sleep deprivation.[5] The ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) suggests various restrictions and reforms, including the maximum 80-hour work week (which is still twice the US standard 40-hour work week).[6] A residency must adhere to these restrictions to gain accreditation. However, there has been little change, as compliance is self-reported.[7]

Duty of Loyalty

edit

A second legal obligation of professionals is the duty of loyalty, an obligation to prevent conflicts of interest and to act in the interest of one's company.[8] That is, one must put their company above themselves and competitors. This precludes things such as insider trading, as it promotes individual interests at cost to one's company. A common extension of the duty of loyalty is the non-compete clause. Such a clause says that during employment, and often for a time after, one cannot perform work for a competitor.[9] Companies often also have clauses regarding IP assignment, asserting that the company gets ownership of any patent or invention created while employed, even if done outside of work.[10] These policies help enforce an employee's loyalty to the company.

Estrangement of Labor

edit

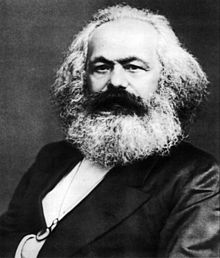

Karl Marx's Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts describe a concept of "estrangement" or "alienation" of labor that can help us make sense of the ownership question. In the first form he describes, this is a separation of the worker from the products of his labor. At no point does a laborer own the product they are producing; instead, their labor is bought and sold as if it were an object.[11][12]

In feudal times, a farmer would work land owned by a lord, and give a (fixed or proportional) part of the land's yield to that lord. The farmer owed the lord that product as rent, but the ownership of the product remained with the farmer. In a modern economy, some professionals such as artisans and freelancers in various fields still maintain this model: the product, rather than labor, is sold. However, many people today perform either wage or salaried labor: they are paid for a quantity of work measured either in time or as fulfillment of certain duties. There may not be a concrete product produced (for instance, in the retail sector), or there may be one produced in which the laborer does not have ownership (as in software engineering).

While labor can be bought and sold, the labor is still voluntary (under the first form of estrangement of labor). Furthermore, the laborer sells some quantity of their work; they may decide to undertake additional labor to sell (or to sell the products of) elsewhere.

In a moonlighting-friendly contract or workplace, the worker's (professional's) labor is therefore only partly estranged; an employer purchases either the professional's product, or a part of the professional's total labor, and the professional may do what they will with the remainder. However, when contracts include non-compete or assignment clauses- that is, clauses that restrict or change the ownership of "moonlight" labor or its products- the professional has sold more than a fixed quantity of their labor. Contracts may contain clauses that assign all products created by the professional to a company's ownership, even when such products were not created with the encouragement, consent, or even knowledge of the company.[13]

Self-directed labor is intrinsically different from assigned labor at a day job; it provides opportunities for a professional to explore and experiment, to take risks, and to investigate new ideas. Marx notes that non-alienated labor is necessary for a feeling of fulfillment; in Wolff's terms, it acts as "a confirmation of [the producer's] powers".[11] When one wholly owns the products of one's labor, and all the rewards thereof, one may perform to a higher (rather than a minimum) standard. One may also be willing to take greater risks or to explore unusual paths which a group (or manager) would dismiss.

Contracts with anti-moonlighting provisions seek to capture the benefits of self-directed labor; they imply the purchase of the employee's intuition, intellect, and creativity. In fact, assignment clauses allow companies to gain the rewards of professionals' investigations into new territory without assuming the risk, such as when employees begin startups in addition to their contract labor.

Company Affordances

editCompanies have widely different policies regarding moonlighting. Some restrict it completely, while others encourage it, as they see the benefits of such self-directed labor.

Common Moonlighting Policies

editMoonlighting itself is legal, but employers often restrict it to a certain extent. Many companies include moonlighting policies in their employment agreements to protect themselves from the risks of moonlighting. By including these clauses, employers have legal grounds to control their employees' moonlighting behaviors. These clauses hold employees accountable and ensure that any moonlighting jobs do not interfere with their primary employment.

The most common type of moonlighting policy is a non-compete agreement. This type of agreement ensures that an employee can not work for a competitor of their employer, while employed and even for a certain time after their employment ends.[14] This clause protects companies by preventing their employees from sharing private company information with competitors. Non-compete agreements also benefit companies by discouraging employees from leaving their jobs for another position with a competitor, allowing employers to receive more benefits from valuable employee training.[15]

Other company policies that restrict moonlighting include: no secondary employment policies, no self-employment policies, and notification requested first policies.[16] Each of these policies gives an employer a certain degree of control over their employees' behaviors. A company may use a no secondary employment policy or no-self employment policy to keep their employees dedicated to their job. When an employee moonlights, their performance at both jobs may be affected. So, by restricting secondary employment or self-employment, employers ensure that they get their employees' best work. On the other hand, some companies include a clause in employment agreements that requires their employees to notify them before taking on additional work. This gives the employer control over an employee's moonlighting behavior and allows them to deny the employee's request to moonlight if they foresee potential conflicts.

Often, companies also enforce intellectual property limitations. Intellectual property clauses vary widely but essentially designate the ownership of ideas to either the employer or the employee. These clauses protect companies by ensuring that the intellectual property that their employees create remains property of the company, even if their employees moonlight.[17]

Despite implementing moonlighting policies in employment agreements, some companies do encourage their employees to take on additional work, as long as it does not interfere with their primary job.

Corporate Moonlighting

edit

Google sought to encourage self-directed labor through its "20% time" policy.[18] This policy stated that 80% of an employee's time should be spent on the job they were hired to do, and the other 20% can be spent on something they are interested in that still benefits the company. Google has since removed this policy and unofficially adopted a "120% policy".[19] This means that employees should only work on personal projects once they have completed their obligation to their position. However, personal projects are still encouraged, and employees have free range to use company resources. This allows employees to moonlight, but maintains Google's control and ownership of the moonlighting projects. Google recognizes that when someone is passionate enough to work on a side project, they will often produce very beneficial results. By allowing employees the freedom to work on personal projects, Google keeps their employees satisfied while still ensuring their product ownership.

Twitter encourages its employees to undertake self-directed work through Hack Week events. Employees start new projects that may benefit the company (or that may just be fun), but the projects are undertaken at the employees' discretion. As with the 20% time policy, this allows the company to use innovations and positive results from their employees' experimentation.[20] BrightTag, SUSE, and Linkedin (among others) also hold hack weeks or analogous events.[21][22][23]

Moonlighting for Startups

editMany start up founders advise people trying to start their own companies to keep their day jobs as they try to get their new venture off the ground.[24] Starting a company as a moonlighting project reduces the financial risk inherent in a young company. The first few months of a startup project typically do not have any financial return, so the income security from a day job allows one to spend the time necessary to give their venture a fighting chance. Starting a new company while still employed can often cause a conflict between the employee and their employer. Companies often have specific clauses and restrictions that either prohibit an employee from moonlighting, or that claim ownership of anything they produce. Starting such an intensive project will likely shift the attention of the employee away from their primary job and potentially interfere with both their duty of care and their duty of loyalty. Thus, moonlighting for a startup must be done with great care.

Hasan Luongo

editHasan Luongo demonstrated the potential dangers of moonlighting for a startup when he started a company as a moonlighting endeavor.[25] While working for an unnamed company, Luongo was struck with an idea for a new site he called PromoterForce. This site would serve as a web-based referral marketing system for small professional service teams. He began working on this site primarily from home, but occasionally spent time at his office developing and promoting the site. When his employer discovered this, he was fired immediately for using company resources on the project. To the company, his time at the office was a company resource. Furthermore, the company sued him for the rights to his site because company resources had been used in its development. Hasan eventually settled out of court, paying significant reparations and ending without a job.[26] Luongo is one of the few people to openly talk about their negative experiences with moonlighting, and his experience shows the possible ramifications of moonlighting when anti-moonlighting clauses are in effect.

Motivations for Moonlighting

editA 2017 study reports that 4.9 percent of workers moonlight, or hold more than one job at a time.[27] These workers moonlight for various reasons. The majority working the second job for the additional income to help meet household expenses or to pay off debts. Others work a second job for different reasons, including enjoying the work, gaining experience, and making connections.[28]

Employers are often wary that taking on second jobs may affect employee performance, but they also often see benefits of having employees who moonlight. For employers, a primary benefit of moonlighting is that it reduces the pressure for them to increase employee wages and hours. Additionally, side jobs may increase an employee’s personal satisfaction as it can be a creative outlet and can reduce financial stress. Moonlighting can also directly benefit a company as it can improve the employer’s or company’s reputation. For example, if an employee moonlights by teaching something related to their primary job, the employer can gain visibility and business from the employee association.[29]

Moonlighting as portfolio

editOne of the main focuses in the interview process for software positions are personal projects.[30] The work that an individual has done in the past is one of the most reliable gauges of their abilities. Due to many non-disclosure agreements though, interviewees are often unable to fully discuss work they have done in previous jobs. However, personal projects do not have the same restrictions, and the drive required to complete a project outside a work environment is an attractive trait. Once a person has been hired however, many companies restrict the ability to continue such projects.

Moonlighting as interview

editThe CEO of the company GroupTalent, Manuel Medina, proposes that moonlighting is a better alternative to interviews for software professionals.[31] Instead of coming in for an interview, an applicant is placed in contact with a current development team that is working on a real project for the company. In addition to the applicant's "day job," the applicant uses moonlighting time to get exposed to the work the company does, as well as the culture of the development team they would work with. If the company is pleased with the work the applicant has done, and the applicant is comfortable with the work and culture of the company, the hire is made. Medina notes that many companies still think of moonlighting as a type of "treason" but the current economic situation has made more companies willing to entertain the idea of hiring people this way.

Moonlighting in Practice

editOff Duty Policy Officers

editIn many areas throughout America, it is commonplace for police officers to engage in off duty services. These services are often in the form of security. The contracting firm Off-Duty Solutions advertises protection for business or private security including financial institutions, residential worksites, personal security, VIP security and transportation, commercial worksites, community patrols, and event security and transportation.[32] Police officers are considered ideal for security work due to their training from police academies and departments.

Police officers typically carry their police powers 24 hours a day in their jurisdiction, whether they're on the job or not. This affords them the power to arrest, use force, and use their firearms. Officers can wear their uniform and carry a department issued firearm during off duty security work.[33] Officers follow the same gun rules whether on or off duty, but certain gun possession or use may violate departmental policies. However, according to a ruling by the ninth circuit courts, law enforcement officers acting as security may not be entitled to qualified immunity if involved in an incident where harm is done to another. [34] Qualified immunity protects government officials against lawsuits where an official violated a plaintiffs rights, unless a constitutional right was violated.[35] With full uniformed and armed officers patrolling as security, it can be difficult to determine in what capacity an officer works for the general public.

Questions of loyalty come into question when police officers moonlight as security. Several factors influence an officer's loyalty and create conflict between officers working together at the departments and security firms. Off duty pay rates could, and often do, exceed that of on duty rates. The higher paying position can shift an officer's priorities, causing them to favor work as security and negatively impacting on duty performance. An increased off duty pay rate encourages officers to work more hours as security, leading to fatigue while on duty. An officer who recruits other officers to a security firm often receives a bonus. This affects the perception of the importance of security work over that of on duty work. Rank at a security firm also does not follow the ranking structure of the department, causing officers to 'outrank' their commanders and potentially result in abuse of the change in hierarchical status. This could lead to retaliation for perceived injustices, causing tension at both workplaces.[36] It is difficult, if not impossible, for many officers to maintain professional ethics at both employments.

Government Moonlighting

editRoberta Beyer worked with the city of Dayton, Ohio as a recreation facility specialist at the Dayton Convention Center since 2010. She was fired in February of 2017 by the city council for moonlighting since it supposedly conflicted with her work and violated personnel policies. She was originally investigated because she failed to get permission from management to work outside the city. However, Dayton policy didn’t clearly specify when employees were supposed to notify management about their outside employment or what constitutes a conflict of interest. Beyer did not believe that she needed permission from the city since her work with International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees could promote her work as recreational specialist. However, the city claimed she needed permission to work with them because it interfered with her time and responsibility to the city. They also claimed that she acted unprofessionally towards a client and her coworkers and that she gave overtime to another employee to do parts of her job. The Civil Service Board ruled against the city's claims that she neglected her duties and was incompetent and determined that she did not violate the city’s code of ethics. However, the board later reported that Beyer was fiscally irresponsible when she scheduled overtime for the employee to complete her responsibilities, giving a mixed message about the consequences of moonlighting. The Civil Service Board ultimately reduced Beyer’s discharge from the Convention Center to an unpaid suspension.

Following this incident, Dayton updated its vague policies on conflicts of interest, requiring all employees to get departmental approval before seeking outside employment. Many of their employees, like Beyer, already had outside jobs and were told that they could not keep both jobs because of conflicts of interests. The city claimed that this was always a rule but was not explicitly defined with examples of prohibited behavior and conflicts of interest.[37]

Ethics of Moonlighting

editMany professionals question not only if moonlighting is ethical, but also when. The answer varies, but many view moonlighting as a threat to a person's time and dedication to their primary job.

Some companies are vague about prohibited employee behaviors. It is difficult to determine when an individual who moonlights because of their passion and skill set jeopardizes the integrity of a company. A true professional should respect their employer while moonlighting, taking care to follow employee policies and not bring harm to the company. Professionals are officially defined by the following dictionary definition: "of, relating to, or characteristic of a profession."[38] However, a professional is more appropriately defined in the context of one's personal ethics along with their employer's ethics.

Moonlighting questions the idea of knowing oneself. When an individual becomes a part of a company, they take on the company's ethics in addition to their own. Thus, as a professional, they must consider both their personal self as well as the company self. Companies put moonlighting policies in place to protect the company from the risks of moonlighting. However, personal ethics and company ethics should guide professionals (even without legal policies) away from actions that might harm the company.

References

edit- ↑ "moonlighting, n.". OED Online. March 2014. Oxford University Press. [1] (accessed April 09, 2014).

- ↑ "General Duty of Care", Western Australia Department of Commerce, available at http://www.commerce.wa.gov.au/worksafe/content/about_us/legislation/OSH_Act/General_Duty_of_Care.html

- ↑ Kwo, Elizabeth, "Moonlighting for Extra Money", Medscape, available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/761414

- ↑ Stevens, Larry, "Before you moonlight: The ins and outs", http://www.amednews.com/article/20071022/business/310229993/4/

- ↑ Landrigan et al., "Effect of Reducing Interns' Work Hours on Serious Medical Errors in Intensive Care Units", N Engl J Med 2004, available at http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa041406

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions – ACGME Common Duty Hour Requirements", ACGME, available at https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/dh-faqs2011.pdf

- ↑ "The Experts: Are Medical Residents Dangerously Exhausted?", Wall Street Journal, available at http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324503204578318763513170222

- ↑ "An Employee's Duty of Loyalty to an Employer in Pennsylvania," Wolf, Baldwin, and Associates, available at http://www.wolfbaldwin.com/Articles/An-Employees-Duty-of-Loyalty-to-An-Employer.shtml

- ↑ "Non-Compete Agreement", OneCLE, available at http://contracts.onecle.com/type/21.shtml

- ↑ "Intellectual property (IP) assignment agreement: Sample template", MaRS Discovery District, available at http://www.marsdd.com/mars-library/intellectual-property-ip-assignment-agreement-sample-template/

- ↑ a b Wolff, Jonathan, "Karl Marx", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), available at http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2011/entries/marx/.

- ↑ Marx, Karl, "Estranged Labour", Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, trans. Martin Mulligan, available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/labour.htm

- ↑ The authors have seen such clauses in contracts for software engineers.

- ↑ HRDI (2020). HRDevelopmentInfo. What Is Moonlighting, How Legal Is It, and More. https://hrdevelopmentinfo.com/what-is-moonlighting/

- ↑ DiGiacomo, J. (2017, June 12). The Importance of Non-Compete Agreements. Revision Legal. https://revisionlegal.com/corporate/agreements/non-compete-agreements/

- ↑ HRDI (2020). HRDevelopmentInfo. What Is Moonlighting, How Legal Is It, and More. https://hrdevelopmentinfo.com/what-is-moonlighting/

- ↑ Contract Standards (2020, April 16). Intellectual Property Ownership. https://www.contractstandards.com/public/clauses/intellectual-property-ownership#clauses

- ↑ Mediratta, Gharat, "The Google Way: Give Engineers Room", The New York Times, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/21/jobs/21pre.html?_r=0

- ↑ Christopher, Mims, "Google engineers insist 20% time is not dead—it’s just turned into 120% time", Quartz, available at http://qz.com/116196/google-engineers-insist-20-time-is-not-dead-its-just-turned-into-120-time/

- ↑ "Hack Week @ Twitter", available at https://blog.twitter.com/2012/hack-week-twitter

- ↑ Wendland, Dave, "BrightTag Hack Week: Episode III", available at http://www.brighttag.com/2014/02/11/brighttag-hack-week-episode-iii/

- ↑ "Hackweek", available at https://hackweek.suse.com/

- ↑ Nash, Adam, "10 Ways to make Hackdays work", available at http://blog.linkedin.com/2011/06/09/10-ways-to-make-hackdays-work/

- ↑ "The Moonlighting Survival Guide", Startup Law Blog, available at http://www.startuplawblog.com/2011/08/05/the-moonlighting-survival-guide/

- ↑ Luongo, Hasan. "The Dangers of Moonlighting", GIGAOM, available at http://gigaom.com/2007/05/22/the-dangers-of-moonlighting/

- ↑ Luongo, Hasan. "The Dangers of Moonlighting II", GIGAOM, available at http://gigaom.com/2007/06/06/dangers-of-moonlighting-ii/

- ↑ Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018, July 19). 4.9 percent of workers held more than one job at the same time in 2017. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2018/4-point-9-percent-of-workers-held-more-than-one-job-at-the-same-time-in-2017.htm?view_full

- ↑ Bureau of Labor Statistics (2000, August). Issues in Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/archive/when-one-job-is-not-enough-pdf.pdf

- ↑ Miller, Bridget (2017, July 28). Why Should Employers Support Moonlighting? HR Daily Advisor. https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2017/07/28/employers-support-moonlighting/

- ↑ Fairley, Andrew, "Top 5 Interview Questions To Ask Software Developers", Undercover Recruiter, available at http://theundercoverrecruiter.com/5-interview-questions-for-software-developers/

- ↑ Medina, Manuel, "Moonlighting is the New Job Interview", GroupTalent, available at https://grouptalent.com/blog/moonlighting-is-the-new-job-interview

- ↑ Off-Duty Solutions. (n.d.) "Services", available at https://www.offdutysolutions.com/security-services

- ↑ Coble, C. (2018, September 5). "Legal Authority of Off-Duty Cops". FindLaw. available at https://blogs.findlaw.com/blotter/2018/09/legal-authority-of-off-duty-cops.html

- ↑ Touchstone, J. (2017, August 30). “Ninth Circuit Rules No Qualified Immunity for Off-Duty Police Officer Working As Private Security Guard”. CPOA: Leading Edge. Available at https://cpoa.org/ninth-circuit-rules-no-qualified-immunity-off-duty-police-officer-working-private-security-guard/

- ↑ LII. (n.d.). Legal Information Institute. "Qualified Immunity". available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/qualified_immunity

- ↑ O'Hara, P. (2017, March 3). Monetizing the police: Corruption vectors in agency-managed off-duty work. Policy and Society, 34(151-164). available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.05.002

- ↑ Frolik, Cornelius (2017, Oct). "Dayton Employee Fired For Moonlighting Gets Job Back", Dayton Daily News available at https://www.daytondailynews.com/news/breaking-news/dayton-employee-fired-for-moonlighting-gets-job-back/TQ1bKR190xg7aS29qL1y2O/amp.html

- ↑ Merriam-Webster.com (2020). Professional. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/professional