Peeragogy Handbook V1.0/Overview

The aim of the Peeragogy Handbook is to lay out effective peer-learning techniques that you can implement "on the ground." We suggest that you look through the Handbook, try a few of these suggestions, and see how they work for you. Then we invite you to return here, share your experiences, ask for feedback, and work with us to improve the Handbook and the field we affectionately call "Peeragogy."

In this part of the Peeragogy Handbook, teams of "peeragogues" have distilled their most important and applicable research and insights from more than a year of inquiry and discussion. Although there's been no shortage of experimentation and formal research into collaborative, connective, and shared learning systems in the past, we've detected a new rumbling among education thinkers that when combined with new platforms and technologies, peer-learning strategies as described here could have a huge impact on the way educational institutions evolve in the future. We've also seen for ourselves how peer learning techniques can help anyone who's interested become an effective informal educator, whether or not that's part of their job description.

Receiving

Peer learning through the ages

edit

In more recent centuries, various education theorists and reformers have challenged the effectiveness of what had become the traditional teacher-led model. Most famous of the early education reformers in the United States was John Dewey, who advocated new experiential learning techniques. In his 1916 book, Democracy and Education [1], Dewey wrote, “Education is not an affair of ‘telling’ and being told, but an active and constructive process.” Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who developed the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, was another proponent of “constructivist” learning. His book, Thought and Language, also gives evidence to support collaborative, socially meaningful, problem-solving activities over solo exercises.

Within the last few decades, things have begun to change very rapidly. In Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age, George Siemens argues that technology has changed the way we learn, explaining how it tends to complicate or expose the limitations of the learning theories of the past [3]. The crucial point of connectivism is that the connections that make it possible for us to learn in the future are more relevant than the sets of knowledge we know individually, in the present. Furthermore, technology can to some degree and in certain contexts, replace know-how with know-where-to-look.

If you want more details on the history, theories, and recent experiments related to peer learning, we have a more extensive literature review available. We’ve also adapted it into a Wikipedia page, which you can edit as well as read.

Which is more fun, skateboarding or chemistry?

edit

- A study group for a tough class in organic chemistry convenes at at the library late one night, resolving to do well on the next day’s exam. The students manage to deflect their purpose for a while by gossiping about college hook-ups and parties, studying for other classes, and sharing photos. Then, first one member, then another, takes the initiative and as a group, the students eventually pull their attention back to the task at hand. They endure the monotony of studying for several hours, and the next day, they own the exam.

- A young skateboarder spends hours tweaking the mechanics of how to make a skateboard float in the air for a split second, enduring physical pain of repeated wipeouts. With repetition and success comes a deep understanding of the physics of the trick. That same student cannot string together more than five minutes of continuous attention during chemistry class and spends even less time on homework for the class before giving up.

Peer-learning participants succeed when they are motivated to learn. Skateboarding is primarily intrinsically motivated, with some extrinsic motivation coming from the respect that kids receive from peers when they master a trick. In most cases, the primary motivation for learning chemistry is extrinsic, coming from parents and society’s expectations that the student excel and assure his or her future by getting into a top college.

The student very well could be intrinsically motivated to have a glowing report card, but not for the joy of learning chemistry, but because of the motivation to earn a high grade as part of her overall portfolio. Taken a different way, what is it about chemistry that’s fun for a student who does love the science? Perhaps she anticipates the respect, power and prestige that comes from announcing a new breakthrough; or she may feel her work is important for the greater good, or prosperity, of humanity; or she may simply thrill to see atoms bonding to form new compounds.

Learning situations frequently bore the learner when extrinsic motivation is involved. Whether by parents or society, being forced to do something, as opposed to choosing to, ends up making the individual less likely to succeed. In some cases it’s clear, but trying to figure out what makes learning fun for a group of individual humans can be very difficult. Often there is no clear-cut answer that can be directly applied in the learning environment. Either way, identifying the factors that can make learning boring or fun is a good start. Perhaps learning certain skills or topics is intrinsically boring, no matter what, and we have to accept that.

Learning patterns

editOne way to think about fun learning is that it’s fun to learn - and be aware that you're learning - new patterns. Jürgen Schmidhuber wrote: “A separate reinforcement learner maximizes expected fun by finding or creating data that is better compressible in some yet unknown but learnable way, such as jokes, songs, paintings, or scientific observations obeying novel, unpublished laws” [4]. So the skateboarder enjoyed coming across new patterns (novel tricks) that he was able to learn; tricks that challenged his current skill level.

Learner, know thyself: a self-evaluation technique

editThe learning contributed and acquired by each member of the peer learning enterprise depends on a healthy sense of self-awareness. When you ask yourself, “What do I have to offer?” and “What do I get out of it?” we think you’ll come up with some exciting answers. In peer learning, whether or not you're pursuing a practical objective, you’re in charge, and this kind of learning is usually fun. Indeed, as we’ll describe below, there are deep links between play and learning. We believe we can improve the co-learning experience by adopting a playful mindset. Certainly some of our best learning moments in the Peeragogy project have been peppered with humor and banter. So we found that a key strategy for successful peer learning is to engage in a self-assessment of your motivations and abilities. In this exercise, you take into account factors like the learning context, timing and sequence of learning activities, social reinforcements, and visible reward. The peeragogical view is that learning is most effective when it contains some form of enjoyment or satisfaction, or when it leads to a concrete accomplishment.

When joining the Peeragogy project, Charles Jeffrey Danoff did a brief self-evaluation about what makes him turn on to learning:

- Context. I resist being groomed for some unforeseeable future rather than for a specific purpose.

- Timing and sequence. I find learning fun when I’m studying something as a way to procrastinate on another pressing assignment.

- Social reinforcement. Getting tips from peers on how to navigate a snowboard around moguls was more fun for me than my Dad showing me the proper way to buff the car’s leather seats on chore day.

- Experiential awareness. In high school, it was not fun to sit and compose a 30-page reading journal for Frankenstein. But owing in part to those types of prior experiences, I now find writing peasurable and it’s fun to learn how to write better.

Two theories of motivation

edit

One of the most prominent current thinkers of (self-)motivation and regulation is Daniel Pink [5], who proposes a theory of motivation based on autonomy, mastery, and purpose, or, more colorfully:

- The urge to direct my life

- The desire to get better at something that matters

- The yearning to do something that serves a purpose bigger than just “myself”

There’s clearly a “learning orientation” behind the second point: in fact, it’s not just a matter of “fun” — ultimately, it’s the sense of achievement that matters.

Learning is given an even more central position in a paper by Thomas Malone [6], who was another thinker who asked “What makes things fun to learn?”. His proposed framework for motivating learning activities is based on the three ingredients fantasy, challenge, and curiosity — this bears a certain analogy to Pink’s framework.

We can easily see how “participation” relates to “motivation” in the sense described here. When I get useful information from other people, I can direct my own life better. When I have means of exploring my fantasies and dreams by chatting then over and exploring some of the elements in a safe way, I’m in a much better position to make something in reality. A solid reputation that comes from being able to help others serves as a good indicator of personal progress, and a sign that one is able to deal with greater challenges. Relationships provide the most basic sense of being part of something bigger than just oneself: et cetera. (Further thoughts on the role of motivation in peer learning appear in our chapter on Motivation.)

Metacognition and mindfulness in peer learning

editMetacognition and mindfulness are words for awareness of how you are thinking, attending, and participating. It can be particularly useful to think about the roles you take on in the project, the kind of contributions you want to make, and what you hope to get out of the experience. These are all likely to change as time goes by.

Potential roles in your peer-learning project

edit- Leader, Manager, Team Member, Worker

- Content Creator, Author, Content Processor, Reviewer, Editor

- Presentation Creator, Designer, Graphics, Applications

- Planner, Project Manager, Coordinator, Attendee, Participant

- Mediator, Moderator, Facilitator, Proponent, Advocate, Representative, Contributor

Potential contributions

edit- Create, Originate, Research, Aggregate

- Develop, Design, Integrate, Refine, Convert

- Write, Edit, Layout

Potential motivations

edit- Acquisition of training or support in a topic or field;

- Building relationships with interesting people;

- Finding professional opportunities through other participants;

- Creating or bolstering a personal network;

- More organized and rational thinking through dialog and debate;

- Feedback about their own performance and understanding of the topic.

Although this first and foremost self-evaluative examination, we find it useful to build in a brief pause at the commencement of the project for each peeragogue to self-define and declare what they plan to bring to the table, what they hope to get out of the experience, how this builds on and expands knowledge, skills, capacities, and preferences. This process of shared reflection primes the group for cohesion and success.

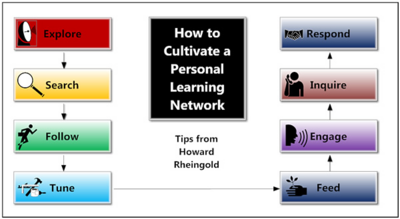

Personal Learning Networks and Peer Learning Networks

editPersonal Learning Networks are the collections of people and information resources (and relationships with them) that people cultivate in order to form their own public or private learning networks — living, growing, responsive sources of information, support, and inspiration that support self-learners.

Howard Rheingold: “When I started using social media in the classroom, I looked for and began to learn from more experienced educators. First, I read and then tried to comment usefully on their blog posts and tweets. When I began to understand who knew what in the world of social media in education, I narrowed my focus to the most knowledgeable and adventurous among them. I paid attention to the people the savviest social media educators paid attention to. I added and subtracted voices from my attention network, listened and followed, then commented and opened conversations. When I found something I thought would interest the friends and strangers I was learning from, I passed along my own learning through my blogs and Twitter stream. I asked questions, asked for help, and eventually started providing answers and assistance to those who seemed to know less than I. The teachers I had been learning from had a name for what I was doing — “growing a personal learning network.” So I started looking for and learning from people who talked about HOW to grow a “PLN” as the enthusiasts called them.”

Strong and weak ties

editYour PLN will have people and sites that you check on often – your main sources of information and learning – your ‘strong ties’. Your ‘weak ties’ are those people and sites that you don’t allow a lot of bandwidth or time. But they may become strong later, as your network grows or your interests expand. This is a two-way street – it is very important that you are sharing what you learn and discover with those in your network and not just taking, if you want to see your network expand.

Peer learning networks

editLater in the Handbook, we’ll talk more about how to develop and share “peeragogical profiles” — in other words how to advertise what you want to learn, and what you’d be interested in helping teach others. A network of people who share their profiles and experiences, and collaboratively work, learn, teach, and communicate is a peer learning network. You’ll also find more information about building this type of a network in our article on Peeragogy for K-12 Educators (the article is useful even if you’re not formally employed as a teacher).

From syllabus and curriculum to personal and peer learning plans

editPart of the effectiveness of peeragogy is that the “syllabus” or “curriculum” ,more generally the learning plan -- is developed by the people doing the learning. You don’t faint with shock when you see the reading list if you helped write it.

In peer learning, having a personal learning plan at the outset helps each participant identify his or her unique learning and teaching proclivities and capabilities, and effectively apply them in the peer setting. In developing your personal plan, you can ask yourself the following questions:

- What do I most need to learn about in the time ahead?

- What are the best ways I learn, what learning activities will meet my learning needs, what help will I need and how long will it take?

- What will I put into my personal portfolio to demonstrate my learning progress and achievements?

Early in the process, the peer-learning group should also convene to develop a peer learning plan. In the Peeragogy project, we used live meetings and forum-style platforms to discuss the group-level versions of the questions listed above. Personal learning needs and skills were also aired via these platforms, but the key shared outcome was an initial project plan. Initially this took the form of an outline of handbook chapters to write, as well as a division of labor into different roles.

Nothing was set in stone, and both the peer group and individual participants have continued to develop, implement, review, and adjust their goals as the project develops. We have stayed sufficiently connected to the original goal of producing a handbook about peer learning that you now have one in your hands (or on your screen). We’ve also added some new goals for the project as time has gone by.

Having a malleable framework enables peer learners to:

- Identify appropriate directions and goals for future learning;

- Review their strengths and areas for development;

- Identify goals and plans for improvement;

- Monitor their actions and review and adjust plans as needed to achieve their goals;

- Update the goals to correspond to progress.

This doesn’t mean you have to let chaos rule, but often in the swirl of ideas and contributions, new directIons took shape and new ideas took hold. We expand on the notion of change in the discussion of roles and motivations.

Self-generating templates

editDocumentation like mind maps, outlines, blogs or journals, and forum posts for a peer learning project can create an “audit trail,” or history, of the process. This record not only serves as a guide for new participants, but also functions as a valuable review tool for all, and a ready-made template for future peer-learning projects. As you mine the documentation of a past peer-learning project or a completed phase of an ongoing project for effective learning patterns, take the time to validate and compare what you’ve achieved against the goal or mission at the outset. Use the record to reflect and evaluate key elements of the process for you as a facilitator and as a member of the peer learning group. Update your plans accordingly.

written by OLWETHU ROAD

From corporate training to learning on the job

edit

Today’s knowledge workers typically have instant, ubiquitous access to the internet. The measure of their ability is an open-book exam. “What do you know?” is replaced with “What can you do?” And if they get bored, they can relatively easily be mentally elsewhere.

This has ramifications for the way managers manage as well as the way teachers teach. To extract optimal performance from workers, managers must inspire them rather than command them. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry put it nicely: “If you want to build a boat, do not instruct the men to saw wood, stitch the sails, prepare the tools and organize the work, but make them long for setting sail and travel to distant lands.”

Jay Cross: “If I were an instructional designer in a moribund training department, I’d polish up my resume and head over to marketing. Co-learning can differentiate services, increase product usage, strengthen customer relationships, and reduce the cost of hand-holding. It’s cheaper and more useful than advertising. But instead of just making a copy of today’s boring educational practices, build something based on interaction and camaraderie, perhaps with some healthy competition thrown in. Again, the emphasis should always be on learning in order to do something!”

From peer learning to peeragogy

editThe idea that we needed a new theory (which we gave the name paragogy [7]) arose out of the challenges we faced doing peer learning. Our aim was to understand how groups and organizations can get better at serving participants’ interests, while participants also learn and becoming better contributors.

Paragogy started out as a set of proposed principles that describe peer produced peer learning -- we’ll say exactly what these principles are a bit further below. We designed them to contrast with a set guidelines for adult educators advanced by Malcolm Knowles [10]. The paragogy principles focused on the way in which co-learners shape their learning context together. Peer produced peer learning is something for “innovative educators” everywhere, working at all scales. You don’t need to have the word teacher, trainer, or educator in your job title. It’s enough to invite someone out to lunch and ask questions, set up a reading group with your friends, or even to tackle a new DIY project following tips from the hardware store clerk or instructions you downloaded from the internet.

Our secret for successful peer learning is actually hidden in plain view: the word “paragogy” means “production” in Greek. We’re particularly interested in how the powerful blend of peer learning and collaborative work drives open source software development, and helps build resources like Wikipedia. But in fact it works equally well in offline settings, from official hacker/maker spaces to garages and treehouses. Projects like StoryCorps show how contemporary media can add a powerful new layer to ancient strategies for teaching, learning, and sharing.

The word “peeragogy” attempts to make these ideas immediately understandable to everyone, including non-geeks. Peeragogy is about peers learning together, and teaching each other. In the end, the two words are actually synonyms. If you want to go into theory-building mode, you can spell it “paragogy”. If you want to be a bit more down to earth, stick with “peeragogy.”

Different ways to analyze the learning process

edit

After doing some personal reflection on the roles you want to take on and the contributions you want to make (as we discussed above), you may also want to work together with your learning group to analyze the learning process in more detail. There are many different phases, stages, and dimensions that you can use to help structure and understand the learning experience: we list some of these below.

- I, We, Its, It (from Ken Wilber -- for an application in modeling educational systems, see [11])

- Guidance & Support, Communication & Collaboration, Reflection & Demonstration, Content & Activities (from Gráinne Conole)

- Forming, Norming, Storming, Performing from Bruce Tuckman.

- The “five-stage e-moderating model” from GIlly Salmon

- Assimilative, Information Processing, Communicative, Productive, Experiential, Adaptive (from Oliver and Conole)

- Multiple intelligences (after Howard Gardner).

- The associated “mental state” (after Csíkszentmihályi; see picture)

- Considered in terms of “Learning Power” (Deakin-Crick, Broadfoot, and Claxton).

Peer learning for one

editHow can you apply the ideas of peer learning on your own? In a certain sense, it’s impossible, but somehow that never stops people from trying. We find a striking parallel between the paragogy principles and the 5 Elements of Effective Thinking proposed by Edward Burger and Michael Starbird in a recent book [12]. It’s a nice short book and worth a read: here, we will just quote the titles of the main chapters to illustrate one possible parallel:

- Changing context as a decentered center ~ Quintessence, Engaging Change: Transform Yourself

- Meta-learning as a font of knowledge ~ Air, Creating Questions out of Thin Air: Be your own Socrates

- Peers provide feedback that wouldn’t be there otherwise ~ Water, Seeing the Flow of Ideas: Look Back, Look Forward

- Learning is distributed and nonlinear ~ Earth, Grounding Your Thinking: Understanding Deeply

- Realize the dream if you can, then wake up! ~ Fire, Igniting Insights through Mistakes: Fail to Succeed

We think that “thinking” is often most effective when it’s done with others, and this is something that Burger and Starbird don’t give much attention. Nevertheless, even when you find yourself on your own in the midst of that challenging DIY project, you can use the techniques of peer learning to understand yourself as a growing, changing part of a shared context in motion. This can contribute to an effective and adaptive outlook on life.

We invite you to approach this book as a “peer learner” -- and we hope the techniques we’ve introduced here will serve you well in the world at large.

Further reading

editA word list for your inner edu-geek

edit- Constructivism

- Social constructivism

- Radical constructivism

- Enactivism

- Constructionism

- Connectivism

On fun and boredom

edit- The Contribution of Judo to Education by Kano Jigoro

- Pale King, unfinished novel by David Foster Wallace

On Paragogy

edit- Joe Corneli’s “Implementing Paragogy” lesson plan, on Wikiversity

- Joe Corneli and Charlie Danoff’s “Paragogy Papers”, on paragogy.net

On Learning vs Training

edit- Hart, Jane. Is it time for a BYOL (Bring Your Own Learning) strategy for your organization?

On PLNs

edit- Shelly Terrell: Global Netweaver, Curator, PLN Builder, blog post, with video

- Will Richardson and Rob Mancabelli, Personal Learning Networks: Using the Power of Connection to Transform Education

- Howard Rheingold’s PLN links on Delicious

Tips from an open source perspective

editCare of User:Neophyte on the Teaching Open Source wiki.

- The Art of Community

- Open Advice

- The Open Source Way

References

edit- Dewey, J. (2004). Democracy and education. Dover Publications.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. MIT press.

- Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1), 3-10.

- Schmidhuber, J. (2010). Formal theory of creativity, fun, and intrinsic motivation. Autonomous Mental Development (IEEE), 2(3), 230-247.

- Pink, D. (2011), Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Canongate Books Ltd

- Malone, T.W. (1981), Toward a Theory of Intrinsically Motivating Instruction, Cognitive Science, 4, pp. 333-369

- Corneli, J. and Danoff, C.J. (2011), Paragogy: Synergizing individual and organizational learning. (Published on Wikiversity.)

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Chicago: Follett.

- Corneli, J., and Mikroyannidis, A. (2012). Crowdsourcing education on the Web: a role-based analysis of online learning communities, in Alexandra Okada, Teresa Conolly, and Peter Scott (eds.), Collaborative Learning 2.0: Open Educational Resources, IGI Global.

- Burger, E. and Starbird, M. (2013). The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking, Princeton University Press.