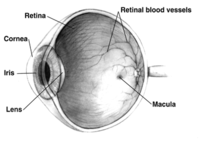

Ophthalmology/Anatomy of the Eye

The structure of the human eye owes itself completely to the task of focusing light onto the retina. All of the individual components through which light travels within the eye before reaching the retina are transparent, minimising dimming of the light. The cornea and lens help to converge light rays to focus onto the retina. This light causes chemical changes in the photosensitive cells of the retina, the products of which trigger nerve impulses which travel to the brain.

Light enters the eye from an external medium such as air or water, passes through the cornea, and into the first of two humours, the aqueous humour. Most of the light refraction occurs at the cornea which has a fixed curvature. The first humour is a clear mass which connects the cornea with the lens of the eye, helps maintain the convex shape of the cornea (necessary to the convergence of light at the lens) and provides the corneal endothelium with nutrients. The iris, between the lens and the first humour, is a coloured ring of muscle fibres. Light must first pass though the centre of the iris, the pupil. The size of the pupil is actively adjusted by the circular and radial muscles to maintain a relatively constant level of light entering the eye. Too much light being let in could damage the retina; too little light makes sight difficult. The lens, behind the iris, is a convex, springy disk which focuses light, through the second humour, onto the retina.

To clearly see an object far away, the circularly arranged ciliary muscles will pull on the lens, flattening it. Without muscles pulling on it, the lens will spring back into a thicker, more convex, form. Humans gradually lose this flexibility with age, resulting in the inability to focus on nearby objects, which is known as presbyopia. There are other refraction errors arising from the shape of the cornea and lens, and from the length of the eyeball. These include myopia, hyperopia, and Astigmatism.

On the other side of the lens is the second humour, the vitreous humour, which is bounded on all sides: by the lens, ciliary body, suspensory ligaments and by the retina. It lets light through without refraction, helps maintain the shape of the eye and suspends the delicate lens.

Three layers, or tunics, form the wall of the eyeball. The outermost is the sclera which gives the eye most of its white colour. It consists of dense connective tissue filled with the protein collagen to both protect the inner components of the eye and maintain its shape. On the inner side of the sclera is the choroid, which contains blood vessels that supply the retinal cells with necessary oxygen and remove the waste products of respiration. Within the eye, only the sclera and ciliary muscles contain blood vessels. The choroid gives the inner eye a dark colour, which prevents disruptive reflections within the eye. The inner most layer of the eye is the retina, containing the photosensitive rod and cone cells, and neurons.

To maximise vision and light absorption, the retina is a relatively smooth (but curved) layer. It does have two points at which it is different; the fovea and optic disc. The fovea is a dip in the retina directly opposite the lens, which is densely packed with cone cells. It is largely responsible for color vision in humans, and enables high acuity, such as is necessary in reading. The optic disc, sometimes referred to as the anatomical blind spot, is a point on the retina where the optic nerve pierces the retina to connect to the nerve cells on its inside. No photosensitive cells whatsoever exist at this point, it is thus "blind".

In some animals, the retina contains a reflective layer (the tapetum lucidum) which increases the amount of light each photosensitive cell perceives, allowing the animal to see better under low light conditions.