Marxism, Communism, and Socialism/Origins of Marxism/

Kautsky traces the roots of Marxism to German Philosophy, British Classical Economics, and French Socialism. Thus, it is best to look at these components in layman's English.[1]

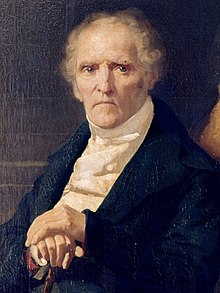

As a note, it is best to say Dialecticians rather than German philosophers influenced Marx and Engels. Hegel is the major player in both cases; he was "the most encyclopedic" of the dialecticians, and German philosophy "culminated" in the Hegelian System[1].

Dialectics

edit

But what is "dialectics"? It is, more or less, a form of logic. It began with the Ancient Greeks as the logic. Literally, dialectic corresponds to "discourse" since the Greek dialectic was simply a discourse between a "pro" and "con" position on an issue.

Hegel changed this, for Hegel had created the "Modern" dialectic. This note will be a step-by-step explanation of his method, so it may be a longer section than the others. Hegel believed the starting point is the immediately given experience at a particular historical juncture. This immediate experience is not "apprehended". Thought must proceed from that which is initially given onwards.

Yet what is "initially given"? This brief moment is when Hegel, a philosopher who is an idealist, is empirical. Or, in other words, this is when Hegel looks at reality (empiricism) rather than only thinking about it.

The goal is not to "create" the world out of pure thought processes, but to reconstruct the "intelligibility" (ability to apprehend by intellect only) of the world. This requires us to assign the fundamental categories that capture that intelligibility.

Hegel writes: "In order that this science (i.e. Hegel's own theory) may come into existence, we must have the progression from the individual and particular to the universal - an activity which is a reaction on the given material of empiricism in order to bring about its reconstruction. The demand of a priori knowledge, which seems to imply that the Idea should construct from itself, is thus a reconstruction only ... In consciousness it then adopts the attitude of having cut away the bridge from behind it; it appears to be free to launch forth in its ether only, and to develop without resistance to this medium; but it is another matter to attain to this ether and to development of it."

Now, what exactly is a "category"? Hegel explains that a category articulates a structure with two poles, a pole of unity and a pole of differences. From this general notion of a category we can go on to derive three general types of categorial structures.

In one, the moment of unity is stressed, with the moment of differences implicit. In another the moment of difference is emphasised, with the moment of unity now being only implicit (or in other words the nature of the moment of unity is left undeveloped). In a third both unity and differences are made explicit together, both are developed.

Another way of speaking of the connections is the concept of dialectical contradiction. Hegel's views on contradiction have been controversial (to say the least). In terms of categories, what he means is fairly straightforward. If a category is a principle that unifies a manifold, then if a category exhibits only the moment of unity, then there is a "contradiction" between what is inherently qua is category (unifier of a manifold) and what it is explicitly (moment of unity alone). Overcoming the contradiction requires the initial category to be negated (in the sense that a second category must be formulated that makes the moment of difference explicit). Yet when this is done the moment of difference will be emphasised at the cost of having the moment of unity implicit. This means there is another contradiction. To overcome this the second category needs to be replaced with a category in which both poles, unity and difference, are each made explicit simultaneously.

Hegel is well aware of what contradiction and negation mean in formal logic. He was following a tradition since Plato of using "contradiction" and "negation" as logical operators. The logic is dialectical logic.

British Classical Economics

edit

Classical Economics is a vast school of economic thought which will not be entirely discussed here. Instead, only David Ricardo and Adam Smith will be reviewed.

Adam Smith had argued that value could not have originated in utility. He presented the counterpoint: if utility was the basis of value, how is it that water (which we need to live) is of no value compared to diamonds (which have no use at all)? He came to the conclusion that the labor used to make the commodity determines the value in exchange.

As a general matter, Smith thought, the amount of labor required to produce the goods would determine the rate at which they could be exchanged for one another, though he mentioned some exceptions. If the supply of goods could not be increased by labor, then their value would be determined by their scarcity, and not by the labor embodied in them. Old master paintings would be a case in point -- no more could be produced, since all the old masters were dead, so the price of these paintings could rise to any height without calling forth a competing supply of new production. Monopoly would be another exception. The monopoly would be able to keep the good scarce, preventing any competing new production. The general idea seems to have been the people can always choose to produce for themselves rather than obtaining goods and services in exchange for others. If they must give up more labor to get the good by exchange, then they would produce for themselves instead.

Basically, the work of Adam Smith that is relevant to Marxism is summed up to a single proposition: Exchange Value must depend on something common to all goods; embodied labor is the one common factor on which exchange value depends.

Ricardo essentially reformed the Labor Theory of Value so value wasn't "entirely" based on labor, although a large portion of value is. He theorized about the influence of machinery affecting value. Ricardo saved the labor theory of value from a serious objection. The objection had to do with land and rent. On the one hand, land rent seems to be a cost of production -- shouldn't the "natural price" of an agricultural product depend on the rent of land? On the other hand, labor will be more productive on land that is more fertile. Crops grown on fertile land will cost less labor. Does that mean it has less value?

I'll skip the math and come to Ricardo's conclusions. It is the labor required for production on marginal land (the next unit of land) that determines the normal price or value of agricultural products. And the surplus of production on more fertile land is "absorbed" by rent. Landowners don't have to do anything to earn this rent -- they get it automatically as a result of the competition for fertile land.

Ricardo fortified the Labor Theory of Value from most criticisms. There were three main vulnarable points: absolutely scarce goods, international trade, and monopoly. Marx played with these, which will be discussed later.

French Socialism

edit

French Socialism can be summed up as the rejection of capitalism. All sorts of outlandish ideas have been associated with French socialism (e.g. polygamy, etc.).

French socialism is only one name of the concepts. Marx referred to them as utopian socialism. Marx grounded his theory in scientific materialism (i.e. beyond physical reality there is nothing), and thus criticized the Utopian socialists for not having a basis in reality for their theories.

The utopian socialists explained that "somehow" everything will fit together into an ideal society. Of course they never bothered to investigate how socialism would come about. They wrote instead of what socialism is.

This may not seem like a bad idea, but to Marx it was a grievous error. Marx explained his theory with historical materialism, which is our next topic.

References

edit- ↑ Moses Hess developed this threefold analysis in his book Die europäische Triarchie (1841) which was first plagiarised by Karl Kautsky Les Trois Sources du Marxisme (1908) and then by Lenin - The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism (1913).