Exercise as it relates to Disease/Osteoporosis and resistance training. The dense connection

This is an analysis of the journal article “Effects of one year of resistance training on the relation between muscular strength and bone density in elderly women” by E C Rhodes, A D Martin, J E Taunton, M Donnelly, J Warren, J Elliot (1999).[1] The Wikibook review has been created by u3096476 as a part of an assignment for the unit Health Disease and Exercise at the University of Canberra.

What Is The Background To This Research? edit

Osteoporosis in the elderly society is a deadly chronic condition that silently affects people until diagnosed or too late. Recent research has linked progressive resistance exercise (PRE) to strengthening bones and muscles and supposedly slowing the effects of Osteoporosis.[1]

What is Osteoporosis?

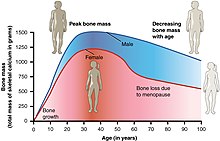

Osteoporosis is a common chronic condition that causes bones to become brittle and weak by losing their density.[2] This condition affects 70% of people over 80 and around 15% of Caucasian people over 50. Women are more susceptible to the condition as estrogen (a hormone that protects bones) rapidly decrease after menopause which causes bone lose. This leads to an increase chance of bones becoming fractured which is a serious problem for elderly people as it can cause chronic pain, disability or even premature death.[3]

The purpose of this research was to investigate the long term effects of resistance training on dynamic muscular strength and bone mineral density (BMD) on elderly women. The study is based on the Wolff’s Law theory of bone modeling which states that “a bone in a healthy person or animal will adapt to the loads under which it is placed”.[4]

Where Is The Research From? edit

The study was conducted in the following facilities listed below

- School of Human Kinetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

- Allan McGavin Sports Medicine Center

- STAT Unit, Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Center, Vancouver

Correspondence to: Dr E C Rhodes, School of Human Kinetics, War Memorial Gymnasium, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1, Canada.[1]

What Kind Of Research Was This? edit

This study was a case control study. Case control studies are retrospective and aim to observe and measure a population with a specific illness or disease (Case) and then compare them with populations without the disease (Control).[5]

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Useful at establishing associations | Retrospective, thus having to recall data can lead to error. |

| Good for studying illness & disease | Finding control groups can be difficult |

| Typically inexpensive | Typically, randomized controlled trials provide better evidence. |

What Did The Research Involve? edit

- 44 participants to meet criteria and take medical screenings

- Voluntary split into two groups (exercise and control)

- Control continued daily lifestyle and exercisers trained PRE for 52 weeks

- Weights lifted a rate of 75% 1 repetition maximum (RM) for 3 sets of 8 repetitions

- Fully supervised with regular check ups

- Targeting major muscle groups

- Grip strength, skin folds and flexibility measures were recorded

- BMD measured with dual x-ray absorptiometry (Lunar DPX).[1]

What Were The Basic Results? edit

Basic results showed increases in muscle strength increases that ranged from 19 to 53% in exercises. In conjunction with the strength gains it showed significant changes in BMD in the femoral and lumbar region.[1] Analysis of covariance was used for statistics and it showed large strength gains (p<0.01) in bilateral bench press (>29%), bilateral leg press (>19%) and unilateral biceps curl (>20%).[1] There were no significant changes in flexibility, grip strength or anthropometry in either groups which was believed to be because the exercise regime focused on strength, which resulted in little change to body composition or flexibility. Strength gains and BMD were almost parallel with changes in dynamic leg strength and femoral neck, Ward’s triangle and the lumbar spine.[1]

Table: Pre and Post changes in BMD in the Femoral Neck.[1]

| Exercise | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (mean) | Post (mean) | Pre (mean) | Post (mean) | |

| BMC (g) | 3.97 (0.21) | 4.02 (0.22) | 3.71 (0.27) | 3.48 (0.19) |

| Area (cm2) | 4.82 (0.30) | 4.87 (0.28) | 4.81 (0.28) | 4.78 (0.22) |

| BMD (g/cm2) | 0.82 (0.11) | 0.83 (0.12) | 0.78 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.10) |

BMC=Bone mineral content

There were some limitations to the study as after 3 months of supervised exercise, the groups were ordered to self-report their exercises in a log book in which 86% of the exercise subjects regularly attended sessions which is still a good figure.[1] Retrospective data needs to be recalled and errors can occur i.e. Subjects overestimating results to cut corners in exercise. Regardless, there is a certain relationship between resistance training and bone mineral density; with regular exercise and constant recalibration of weights there is a very strong suggestion that it could slow the effects of osteoporosis.[1]

How Did The Researchers Interpret The Results? edit

These results were interpreted by the researchers as a clear indication that PRE in elderly woman would improve functional capacity and slow the progression of osteoporosis. There would be less chance of falls from strength gains and less chance of breaks due to greater BMD.[1] This would inevitably mean that the elderly would be able to continue to live independently and would result in a better quality of life.[6]

What Conclusions Should Be Taken Away From This Research? edit

There have been serval similar studies on elderly subjects and strength training which have had very similar or better signs on strength gains. Unfortunately, literature in the same area of study has failed to draw a significant link between muscle strength and its influence on bone density.[1] Some principles of maintaining bone density didn’t make sense as theoretically a muscle contraction would directly reflect on the skeletal sight. Where as results stated that “Although the anatomical origin of the quadriceps muscle groups is not on the lumbar spine, the agonist/antagonist effects of the hip flexors and the knee flexors would directly impact the lumbar spine”.[1]

The researches stated that the effects of PRE on BMD is still inconclusive as the results from the data were not statically significant although they did show positive changes. As bone growth is also slow they agreed that in order to see significant changes in bone growth, one year of exercise might be insufficient and the training periods would need to be extended.[1]

What Are The Implications Of This Research? edit

This research has shown exercise interventions appear to be beneficial in delaying the onset of osteoporosis. However further research needs to be conducted to understand physiologically how this is of benefit and how to best implement strategies to reduce the onset of osteoporosis.[1]

Further reading edit

For more information on the effects of osteoporosis and the benefits of exercise use the following links, alternatively contact your GP for additional information.

- Osteoporosis Australia: http://www.osteoporosis.org.au[7]

- Osteoporosis signs and symptoms: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoporosis/symptoms-causes/dxc-20207860[8]

- Exercise and Osteoporosis: http://www.webmd.com/osteoporosis/guide/osteoporosis-exercise[9]

- Nutrition and Osteoporosis: http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/resource/osteoporosis[10]

References edit

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Effects of one year of resistance training on the relation between muscular strength and bone density in elderly women -- Rhodes et al. 34 (1): 18 -- British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1999. [ONLINE] Available at: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/34/1/18.full#sec-1. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ What is osteoporosis? -- Christodoulou and Cooper 79 (929): 133 -- Postgraduate Medical Journal . 2002. [ONLINE] Available at: http://pmj.bmj.com/content/79/929/133.full. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ What is it? | Osteoporosis Australia. 2016. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.osteoporosis.org.au/what-it. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ Pearson, O. M. and Lieberman, D. E. (2004), The aging of Wolff's “law”: Ontogeny and responses to mechanical loading in cortical bone. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 125: 63–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20155 [ONLINE] Available at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15605390. [Accessed 26 November 2016].

- ↑ Study Design 101 - Case Control . 2011. [ONLINE] Available at: https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/casecontrols.html. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ Taunton JE, Martin AD, Rhodes EC, et al. Exercise for the older woman: choosing the right prescription. Br J Sports Med1997;31:1–6.

- ↑ Osteoporosis Australia. 2016. Osteoporosis Australia. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.osteoporosis.org.au. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ Symptoms and causes - Osteoporosis - Mayo Clinic. 2016. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/osteoporosis/symptoms-causes/dxc-20207860. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ WebMD. 2016. Best Osteoporosis Exercises: Weight-Bearing, Flexibility, and More. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.webmd.com/osteoporosis/guide/osteoporosis-exercise. [Accessed 26 September 2016].

- ↑ Osteoporosis | Nutrition Australia. 2012. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.nutritionaustralia.org/national/resource/osteoporosis. [Accessed 26 September 2016].