Crowdsourcing/Print version

| This is the print version of Crowdsourcing You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

Crowdsourcing: the Wiki Way of Working explains an approach to organising work that is in some ways the opposite of traditional planning and management. It draws out some lessons from the most visibly successful crowdsourcing projects that support education and research, including Wikipedia. It shows how these community-based projects, despite their unorthodox methods, share educational and scholarly objectives with more traditional institutions and projects. It suggests ways in which those institutions and projects can benefit from working with Wikipedia and the wider Wikimedia community.

It was originally published in February 2014 as an infoKit on the Jisc infoNet site and is reproduced here under its CC-BY-SA licence. It can be read as a series of self-contained points or case-studies, or as a journey from theory to practice. Development of the infoKit was funded by Jisc and Wikimedia UK.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive manual of crowdsourcing. The topic is also addressed in parts of the Wikibooks Citizen Science and Lentis: The Social Interface of Technology.

Contents

- Two approaches to complex tasks

- The Wikipedia way

- Division of labour

- Wikipedia, the triumph of crowdsourcing

- Progress without a plan

- The drive for quality

- Summing up

- Free content and open processes

- Making soup with stone

- Intellectual property

- Network effects (the power of one)

- Summing up

- Community design

- Norms and culture

- A shared goal

- The right kind of goal

- Summing up

- Gamification

- Managing motivations

- Recognition and badging in Wikipedia

- Summing up

- Crowdsourcing in practice

- Division of labour for a scholarly database

- Defining progress: geographical data

- Motivation: documenting a town

- Crowdsourcing the restoration and reuse of images

- Keeping everybody happy

- Image restoration

- Contextualisation

- Improving image metadata

- Summing up

- Further reading

Two approaches to complex tasks

There is something fundamentally appealing about the notion that out of millions of heads can come information … larger than the sum of its parts. Imagine if the world’s people could write poetry or make music together; these are unbelievable ideas.—Mahzarin Banaji, quoted by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, 2010

Imagine you have a big, complicated task which can be broken down into many small steps. We will set in motion a machine – that is, a digital computer – to carry out the task. Here are two possible approaches.

Computer 1 works in sequence through its list of instructions. If it has to add two numbers, it grabs the two numbers from wherever they are stored, puts them through its adding machine, sends the answer to be stored and then clears its workspace to prepare for the next instruction. It only begins a step once the previous one is complete.

Computer 2 is completely different. Parts of Computer 2 are constantly breaking off and other things are constantly sticking to it. It thus exists in a state of near-equilibrium with its environment. However, it makes progress because the equilibrium is not exact. When part of its structure corresponds to part of the correct solution to its problem, Computer 2 becomes a little bit more stable. So over time it grows bigger and more complete, even though from minute to minute it is rapidly changing in a way that seems chaotic. Just under half the steps in the development of Computer 2 are reversals of previous steps.

Another difference with Computer 2 is that a constant proportion of its steps give incorrect answers. Asked for 1+1 it will most of the time say 2, but every now and again give 3 or 4. This is not as disastrous as it sounds, because the answers are so frequently erased and replaced, and correct answers are more stable and more likely to become part of the long-term structure. Still, there is no guarantee that every instruction is carried out correctly.

Here is another difference: Computer 2 is more energy-efficient by a factor of a hundred or a thousand, according to the physicist Richard Feynman. What’s more, these two machines are things we encounter all the time. Computer 1 is a microprocessor of the type we have in our computers, our phones, our cars, and ever more everyday objects. Computer 2 is DNA.

The long-term sustainability of DNA is not in question. Microprocessors had to be brought into existence and need constant external power because of their relative inefficiency. By contrast, DNA just happened when certain molecules came together. DNA does not need to be plugged into the wall. Given enough time and the opportunity to make lots of mistakes, DNA has made things that seem highly designed for their environment, all without any kind of forward planning.

The DNA approach may be unacceptable when guarantees of reliability and quality are paramount. An astronaut getting ready for launch won’t be happy to be told that 90% of the rocket’s components are definitely working properly. Either everything has been checked and tested, or the rocket is not likely safe. So we would not use the DNA approach in building a rocket. Then again, not every task is like this. The different articles in an encyclopedia do not depend on each other in the same way as the parts of a rocket: mistakes in the art history articles do not ruin the usefulness of the articles about military history. Similarly with creating a multilingual dictionary, a database, or a museum catalogue; partial success gives partial utility, not zero utility.

We could say that the DNA approach works to create things that are organic. In practice, organic means:

- Modular: a failure of a part does not mean a failure of the whole

- Visible in quality: it is possible to evaluate the quality of a part, independently from the whole

Open up an encyclopedia, database or educational materials to the public (the “crowd”) for editing and people may contribute, whether to demonstrate a skill, promote altruistic goals, to educate themselves, or for other reasons. It will also invite vandalism, hoaxes and other misbehaviour.

What makes crowdsourcing worth it is the net change over time. In a truly open system, it is not feasible to prevent vandalism entirely, but it is possible to structure it so that the negative contributions are outweighed by improvements. Achieving this is the challenge of successful crowdsourcing.

Summing up

It is not the best way to do everything, but crowdsourcing offers huge efficiency gains for certain kinds of large, complex tasks. Managing it requires a different way of thinking that accepts unpredictability, imperfection and diminished control. Crowdsourced effort is hard to control, but the absence of central control gives it its efficiency and strength.

The Wikipedia way

There was never a business plan for Wikipedia. … For something completely new, the business plan is going to be a bunch of made-up nonsense.—Jimmy Wales

Wikipedia and its sister projects differ from a conventionally-managed project in the same way the previous section’s DNA computer differs from a microprocessor. This section introduces some of those differences.

Division of labour

Imagine I’ve enlisted three people to write a handbook. Amy has an advantage over the others in finding and summarising research but doesn’t write the most elegant English; Ben is best at sourcing, adapting, and captioning images; and Chris, a grammar pedant, is strongest on copy-editing. A natural way to organise them is to divide them into different roles: Amy the writer and Ben the illustrator will pass drafts on to Chris the copy-editor.

Rather than labelling the workers, an alternative – more in the spirit of the DNA computer – is to label the work. The pages of the draft get tags to suggest "This needs updating", "This needs illustrating", "This seems finished: needs review," and so on. Tagged pages go into a queue, so for example Chris tracks what needs doing by looking at the "in need of a copy-edit" queue. Pages with no tags go into a "This needs a tag" queue. Rather than working after each other in sequence, each person works, when they have time, on the next appropriate item.

Let us also introduce microattribution: each page is labelled with who has worked on it and what they have changed. On paper, this could be done with different coloured pens: in the digital sphere this could be a database of contributions. Not only will it be clear that each finished page was worked on by Amy, Ben, and Chris, but each can demonstrate what they added and none has to worry about others taking credit for their work.

This approach is more responsive than rigorous planning. Chris has a comparative advantage at copy-editing over Ben the illustrator, but Ben is still quite good at it. So if the copy-editing takes longer than expected, the relevant queue becomes backlogged, and the workers notice that Ben can vary his work to reduce that queue. He knows that his work will be credited, not assumed to have all been done by Chris. Sometimes the workers will be in a mood to use their special skills, and at other times they might want to work on something more simple and repetitive: they just have to change the queue they work on.

To extend the metaphor, we could invite strangers into this workplace to see the drafts and their tags, track what they do and add tags if their contributions are problematic. Pedants who cannot stand to see misplaced apostrophes might correct some errors in the drafts, and even if the crowd’s contributions are low-value like this, the job still gets done more quickly. Crowdsourcing does not mean that all the work is done by the "crowd". Crowdsourcing can include engaging a wider public to collaborate with professionals or to add a particular value to work they are already doing.

This is the way of working enabled by a wiki. While by definition a wiki is a site that can be edited quickly and easily ("wiki" being a Hawaiian word for "quickly"), it is perhaps better seen as a technology for organising work, simplifying what would rapidly get out of hand if done with post-its and coloured pens. Tags, categories, queues, backlogs, and user contribution records all help to break down a high-level task ("create a handbook of publishable quality") into small steps, to distribute effort across those steps, and to track progress.

-

A Wikipedia article tagged as “needing inline citations”...

-

...is automatically added to a category of articles with that problem.

Wikipedia, the triumph of crowdsourcing

Wikipedia has become one of the top ten most popular websites on a tiny fraction of the staffing or budget of the others. It has created more than 30 million articles in 13 years, across more than 280 languages, harnessing hundreds of millions of person-hours of work. Clay Shirky estimated in 2010 that around 100 million person hours of volunteer effort had gone into making Wikipedia.[1] Collectively, the Wikimedia sites have around 80,000 active volunteer contributors (defined as those making at least five edits per month) and in 13 years have reached more than two billion edits.

A large proportion of changes made to Wikipedia are reversions of other changes: this is not a failure but a consequence of how easy it is to edit, just as it was integral to the DNA computer that most of its steps are reversals of past steps. A huge number of person-hours have gone into heated-but-pointless discussions, but given how controversy is inevitable in topics like Abortion, 2003 invasion of Iraq, or Capital punishment, contributors’ disagreements have not stopped them creating detailed, extensively referenced articles. Wikipedia has an internal bureaucracy that can be arcane and frustrating for users, but when compared to the scale of bureaucracy required for similarly complex tasks, such as running a university, it could be seen as remarkably un-bureaucratic.

Wikipedia is just the best known of eleven multilingual, freely reusable, volunteer-led projects hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation. These include Wikidata, Wiktionary, and others that will be considered later. "Wikimedia" is the umbrella term encompassing these projects, their communities, national and regional non-profit organisations and related activities such as outreach, research and software development.

The change management infoKit distinguishes four kinds of organisational culture: Collegiate, Bureaucratic, Innovative, and Enterprise. By being very individualistic, consensual, focused on freedom, driven by local cultures rather than global coordination, and focused on the long term, Wikimedia strongly maps onto the Collegiate culture, which also happens to be the culture of old, research-focused universities.

Wikimedia projects have glaring imbalances and biases in their output, reflecting that:

- The things needed to contribute – including broadband internet, access to sources, IT skills, free time, and confidence – are not evenly distributed through the world’s population. For example the density of articles, mapped geographically, corresponds strongly to the availability of broadband internet.

- Contributors’ effort goes into writing about what they are interested in.

Several projects that are very similar to Wikipedia have nothing like the same success.[2] Citizendium is almost exactly like Wikipedia except that contributors have to be credentialed experts. Google Knol shared some features with Wikipedia but allowed individual authors to take ownership of articles. So to learn from Wikipedia’s success it is essential to look at its distinctive recipe.

References

- ↑ Shirky, Clay (2010). Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age. Penguin. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-59420-253-7.

- ↑ Mako-Hill, B. (2012) ‘Almost Wikipedia: What eight early online collaborative encyclopedia projects reveal about the mechanisms of collective action’, Wikimania 2012, George Washington University, Washington DC, 14 July.

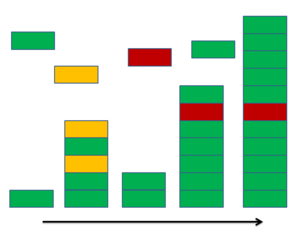

Progress without a plan

One of the ways an encyclopedia is an ideal project for crowdsourcing is that it is strongly modular: it can be broken down into many individual pieces of work which do not depend on each other. It may seem, though, that the whole process depends on detailed planning to create a structure in which crowdsourcing will be successful. In particular, it might seem that the policies and guidelines that define good work have to exist before people start the work.

In fact, Wikipedia did not turn out like this. Policies and guidelines are created by the same process as the articles: public editing and discussion to consensus, often seeded by a very short statement. These policies and standards have evolved with the articles.

In the course of writing the best content, or handling the most contentious disputes, the community has reached consensus on points of style, scope, user conduct and so on. This consensus can then be cited in similar debates or written up as a policy or guideline. Once an article is badged as a “Featured Article”, representing the community’s best work, it can be used as a model for the development of related articles. So the role of good content in shaping policy is as important as policy’s role in shaping content.

Wikimedia has as its vision statement:

a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge.

This statement, which reflects both the long-term focus of the project and the moving target it is aimed at, is known by all active contributors and cited as a guiding principle in on-wiki discussions.

Wikipedia’s role is to be a general-audience encyclopedia in the same sense as Britannica. This goal is literally tangible for those generations who grew up with print encyclopedias. Having an "old-fashioned" goal is a plus: projects with too novel a goal restrict their own growth because not enough people can grasp the goal and decide whether it is being achieved.[1] The Wikimedia and Wikipedia goals are made more concrete for contributors when they hear of people benefiting who were previously information-poor, such as the recipients of the One Laptop Per Child project or the use of Wikipedia by schoolchildren in the townships of South Africa.

References

- ↑ Mako-Hill, B. (2012) ‘Almost Wikipedia: What eight early online collaborative encyclopedia projects reveal about the mechanisms of collective action’, Wikimania 2012, George Washington University, Washington DC, 14 July.

The drive for quality

Whereas the tagline “the free encyclopedia anyone can edit” suggests anarchy, newcomers can be surprised by how constrained and rule-bound the project is. The tagline is correct, but does not convey the evolutionary process that Wikipedia actually employs, preserving encyclopaedic contributions while resisting promotional, crank, or other undesirable influences.

A lot of the activity on Wikipedia is behind the scenes, not part of the encyclopedia itself. This includes policies, style guidelines, noticeboards, discussion pages about improving individual articles, “wikiprojects” to improve a topic area, and discussions about user behaviour. A lot of this is geared towards assessing articles on a detailed quality scale, including processes of informal and formal review. An article’s quality rating, if it has one, is visible on clicking “Talk” at the top of the page on the desktop version of Wikipedia.

- The Wikipedia quality scale

| Class | Criteria |

|---|---|

| FA | The article has attained featured article status. Detailed community review process. |

| GA | The article has attained good article status. Specific review process. |

| B | The article is mostly complete and without major issues, but requires some further work to reach good article standards. |

| C | The article is substantial, but is still missing important content or contains a lot of irrelevant material. The article should have references to reliable sources, but may still have significant issues or require substantial cleanup. |

| Start | The article has a usable amount of good content but is weak in many areas. Quality of the prose may be distinctly unencyclopedic; but the article should satisfy fundamental content policies such as notability, and provide sources to establish verifiability. |

| Stub | The article is either a very short article or a rough collection of information that will need much work to become a meaningful article. It is usually very short, but if the material is irrelevant or incomprehensible, an article of any length falls into this category. |

Review of a Wikipedia article is different from peer-review of an original research paper for a journal. Someone who “reviews a paper” is also reviewing the research that it reports. It takes expert knowledge to infer, from the paper, how the research was conducted, whether it used the best available methods, and hence whether the research is reliable and significant.

By contrast, a Wikipedia article is not a proxy for something else. The article itself, and its relation to its sources, are the target of the review. The reviewer does not have to infer things that happened away from Wikipedia. The reliability of the article comes from its citations (which is why Open Access research, verifiable by a wider audience, is of more use in improving Wikipedia than paywalled research). So while it is useful for reviewers to be aware of the relevant literature and able to use relevant research tools, it is not essential that all reviewing is done by experts.

Whereas a poorly-written paper reporting significant research might be accepted by a journal and then copy-edited, the reviews on Wikipedia examine the wording and layout in fine detail. Every sentence and citation can potentially be challenged. On the way to Featured Article status, an article typically goes through three review processes, involving at least eight reviewers. While Peer Review and Good Article involve one reviewer (or more if the review is contentious), the Featured Article review is a community process typically involving five or six reviewers. Another contributor reviews the FA discussion to assess whether it has reached consensus.

Whether it involves formal review or not, a quality scale is important in helping contributors work together, rather than against each other. The scale has to be flexible enough to adapt to different subjects, since a summary of knowledge about a battleship is different from a summary of knowledge about an art form. At the same time, the scale has to be cashed out in enough detail to guide individual decisions about progress. Tangible models (other encyclopedias in the case of Wikipedia) make this easier.

Summing up

Wikipedia and its sister sites have not come about by planning the expenditure of effort, but by describing in detail the work to be done, labelling it and giving people a variety of ways to contribute, depending on their knowledge, time, skills and confidence. A crucial part of this success comes from a goal which is appealing, attainable in steps, flexible and tangible enough to be understood by, and inspire, a wide audience. If people are to work for free, they need confidence that their work advances a goal that they admire, and that their involvement will have some visible effect.

Free content and open processes

There’s a lot of stuff I would do for free that I wouldn’t do for a pittance.—Cory Doctorow quoted by Reuters, 14 Jan 2011

For the crowd to improve content, it needs to be technically and legally possible for them to make changes. So crowdsourcing is impossible without at least some commitment to openness and to the rights of the end user. This section explores some factors that have made Wikimedia successful at attracting a large number of contributions, and some ways in which crowdsourcing can be ruined by too much control.

Making soup with stone

In a common European folk tale, a cook is tricked into boiling a "magic" stone in water to make "stone soup". The taste is unappetising, so the cook adds some potatoes to "bring out" the flavour. Other cooks, still unsatisfied, add different herbs and vegetables in the hope of tasting stone soup at its finest. Eventually they all enjoy a delicious, nutritious soup. The stone was not magic, but it was essential to the successful outcome: it was there to create a soup that people would find inadequate and hence would want to improve.

Good articles on Wikipedia usually come from a similar process. They may have begun as a simple definition such as "Cancer is a disease of unrestricted cell growth". Some of the readers, finding that inadequate, might supply details about symptoms of cancer. Others will have found it incomplete or inaccurate in other ways, and added text and references about treatments, diagnosis, biology and so on. Thus, over thousands of edits, a short definition evolves into a detailed and comprehensive article.

This process is only possible because of Wikipedia's unconventional publication process:

- It was technically possible for users to edit the live version of the site

- Users needed no permission to edit

- No lawyers or managers had to sign off on changes

- The owners of the site were prepared to bear the risk of articles being inadequate or even unreliable, for a long time

- Each change was recorded, viewable to the public, and reversible. So the merit of each change could be discussed at any point after it was made

This illustrates the centrality of openness (in its various forms) to the success of the Wikimedia sites. In a technical sense, the wiki was built in an open way to enable public contributions. In a legal sense, Wikipedia is an open resource whose users are free to alter it. The process of development is open in that it is public and auditable.

The concept of “ready for publication” does not apply in Wikipedia or the other projects. Just as the cooks started tasting soup when it only included the stone, it is essential that articles and their flaws are on public display so that people can improve them. The distinction between “published article” and “unpublished drafts” is replaced by tags or badges to show that content has problems or alternatively that it has passed a review. This puts some burden on the reader to take notice of tags and be appropriately critical, rather than assuming that something is true because it is published.

Intellectual property

By default, full copyright applies to new creative works: there is very little that the end user can do in terms of copying or altering them without permission from the owner. Creative Commons licences give a spectrum of different options in which the copyright owner still legally owns the material, but retains more or fewer rights in it, giving advance permission for copies, remixes and derivative works.

The copyright status of the material sets the balance of power between the hosting organisation and the contributors. Hosting organisations might be tempted to use copyright to keep a high degree of control over their content, if not with full copyright then reserving exclusive rights to commercial exploitation. This might seem a desirable move, but it has further effects.

If someone is asked to work in their spare time for the commercial benefit of an organisation, that is less compelling than working in their spare time for the cause of free global education or the advance of knowledge. As well as being a more noble goal, the latter option gives the contributor an assurance they are going to be able to keep and use what they have worked on.

There is a point in this spectrum of rights which defines what are known as free cultural works: text, media, or other works that anyone can use for any purpose, including adapting for their own use and distributing the adapted versions. This mirrors how the word “free” is used in the free software movement. All the contents of the Wikimedia sites (with small exceptions) are free cultural works by this definition.

If Wikipedia were fully copyrighted, improvement of articles would be impossible. Editing and translation of an article creates derivative works in the terms of copyright law. If that required permission of the previous authors, there would be no quick editing.

If the licence were for noncommercial use only, some intended forms of distribution would not be possible, including distribution on a cost-recovery basis. The Wikimedia Foundation have a relationship with a for-profit print-on-demand publisher, PediaPress, which allows users to compile articles into books and to access these or community-created books digitally or in hard copy. This is already being used in universities to create tailored reference works for courses.[1] This would not be a viable tool if PediaPress’s printing and selling of a book awaited permission of the Wikipedia contributors.

The choice faced by Wikipedia is not between more or less control of its content. In practice, the choice has been full control of nothing versus hosting and curation of the largest encyclopedia ever written.

The ShareAlike (SA) clause in the default Wikipedia licence stipulates that any derivative work must be given the same licence as the original. Whereas the attribution clause prevents others from taking your work and presenting it as their own, the SA clause prevents others from taking your work, adapting it, and giving the adapted version a more restrictive licence that restricts commercial exploitation to themselves. This, then, is another way to reassure contributors that they are working for a public commons, not private commercial benefit.

The content, policies, digital media and underlying software of Wikimedia projects are freely and openly available. It is technically possible to take them lock, stock and barrel (without private data like user logins) to another hosting organisation. This possibility gives the hosting organisation an incentive to respect the wishes of contributors, which in turn gives people the confidence to contribute. The same applies to Open Source software projects which build up large communities of contributors. Those contributors know that if they are unhappy with the project’s direction they can take an earlier version of the software and build from that (known as “forking”).

That an entire project can fork is not just a theoretical possibility. The crowdsourced travel guide Wikitravel was hosted by the commercial company Internet Brands, until in 2012 the contributors, complaining of insufficient updates and excessive advertising, forked the site to make WikiVoyage, which is hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation. This is a rare event but it illustrates how free cultural works maintain the balance of power between host and contributors. It also illustrates that it is the good will of the community, not rights in the content, that keeps the project viable.[2]

Where social media sites ask for exclusive commercial rights, contributors have to question whether the service they get from the site is unique and valuable enough to justify giving up some of their rights to their own content. In 2012 the photo sharing site Instagram retracted proposed new legal terms after a backlash from users. The new terms would have given the site a permanent exclusive licence to sell or licence users’ photos.

Wikimedia’s status as a charity without commercial influences is one factor in getting contributions from the public, but it is not a necessary factor. There are commercial entities using wikis and Creative Commons-licensed content to crowdsource reference sites, some of which use the free MediaWiki software that underlies Wikimedia. WikiHow develops tutorials, Wikia hosts thousands of how-to sites and fan sites, and Internet Brands’ original hosting of Wikitravel is another example.

References

- ↑ Wane, P. (2012) ‘Wikipedia Book Creator’, EduWiki 2012. University of Leicester, Leicester, 5-6 September. Accessed: 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Benkler, Y. (2011) ‘Peer Production and Cooperation’, in Bauer, J.M., Latzer, M. (eds.) Handbook on the Economics of the Internet. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Network effects (the Power of One)

Randall Munroe’s cartoon illustrates what seems to be a common user experience of Wikipedia: its web-like structure, linking all kinds of subjects, draws casual readers in to learn about things they would not have anticipated.

Less obvious, but essential to note, is that this effect works for creation as well as consumption. Anyone who learns how to edit articles about bridges also learns how to edit articles about US Presidents, Batman, or clothing, because all articles are in one software platform. Similarly, anyone who learns how to edit articles on Wikipedia also learns how to edit travel guides on Wikivoyage, news articles in Wikinews, and so on. The immediacy of wiki editing (just press "Edit", make a change, then press "Save") means that once someone has a taste for making changes, they can keep doing it whenever they find something they can improve.

There are processes in Wikipedia that require a previously uninvolved editor to review an article and confirm that it meets certain standards, for example Good Article Review. This is usually done on a pay-it-forward basis: a contributor who wants a review of their own article is usually expected to review someone else's contribution, and so on. Hence someone who is fixated on improving one article will, at some point, have to look at other content and decide what improvements it needs.

Contributors come with different intentions. Some want to improve articles about a topic such as their locality, their hobby or a subject they've studied. Others feel best able to contribute in ways that cut across topics: articles in British English, articles with vector diagrams, or articles with embedded geographical data, for example. These different contributors benefit from different categories and navigational tools. Here, the above-mentioned queues (such as "articles with promotional text", "articles awaiting Good Article review", or "articles with broken external links") are valuable tools for helping people find where they can usefully contribute.

Users looking to improve articles of a particular kind use the same navigational tools as users who have come to find that kind of article. So anything that might be used to help readers with navigation can also be used to encourage contributions. Conversely, anything that segments and separates content will discourage some contributions. Separating the collection of articles by topic would make little difference to the topic-focused contributors but would obstruct, and get much less value from, the other kinds of contributor.

Summing up

If the users of a resource are also expected to be contributors, then whatever makes things easier for the readers will indirectly benefit the resource by making it easier to contribute. For this reason, the hosting organisation needs to attend to the balance of power between it and the contributors. Restricting reuse of the content may well lead to there being no content, just as people are less likely to buy from a shop that has no money-back guarantee. Walls around content may keep some contributors in but they keep a larger number of potential contributors from improving it.

Community design

Wikipedia is a social innovation, not a technological innovation. It is a human dialogue and conversation.—Jimmy Wales quoted in Get There Early: Sensing the Future to Compete in the Present Bob Johansen (2007)

Wiki software is used by many different sites for different purposes, not all of which become successful crowdsourcing projects. The site has to function as a community that makes positive contributors feel welcome and destructive contributors unwelcome. It has to encourage people with different interests and opinions to build on each other’s work. The direction taken with this design can make or break the success of the project.

Norms and culture

Are you free to park anywhere you like? There is a sense in which nothing prevents you from parking your car anywhere that can be reached from the road. You are not physically prevented from parking on your neighbour’s lawn or across the middle of the high street, but this does not mean you are free to do it. Drivers know they can only park in certain places. Elsewhere, they risk getting fined or towed away. So in a physical sense, you can park on people’s lawns, but in a more important cultural sense that actually shapes people’s behaviour, you can’t.

Wikipedia and similar communities have that same distinction between what is technically possible and what is culturally allowable. Technical possibility is determined by the software, but what is culturally allowable is decided in policy, values and community consensus. There is scope for interpretation and for human judgement in deciding what contributors are free to do, just as there is scope for a court to decide if someone’s actions count as murder.

It is technically possible to delete all the text from Wikipedia’s Featured Article, replace journal citations with tabloid newspapers, or to copy articles from a blatantly promotional site. This doesn’t mean that Wikipedia regards you as free to do these things, in fact they would be disastrous, even just as an experiment. For vandals, there are consequences: the edits can be undone and the accounts warned, blocked or banned.

So creating a community-driven site involves establishing and enforcing cultural norms and procedures. These answer such questions as:

- How does the community resolve disputes?

- What distinguishes constructive from unconstructive contributions?

- How do you distinguish good-faith but unconstructive contributions (which require educating or nudging the contributor) from intentional disruption (which requires minimising the future damage they can do)?

- How are disruptive contributions punished? How are constructive contributions rewarded?

- What changes are new users trusted to make, and how can they earn greater trust, or have trust withdrawn?

The transparency and perceived fairness of the answers to these and other questions will affect people’s experience of the community and their willingness to contribute.

A shared goal

Wikipedia’s core principles are summed up in "five pillars" which all new users are encouraged to learn. A quick summary is:

- Wikipedia is an encyclopedia

- Wikipedia is neutral

- Wikipedia is free

- Users interact in a civil and respectful manner

- Wikipedia does not work on fixed rules

Which of the pillars is the crucial one for getting people to work together productively, and to discuss each other’s work constructively? The fourth pillar may stand out as the obvious answer because it directly tells users to be civil. However, such rules do not guarantee civil behaviour, or the problems with trolling and abuse in online communities could be solved instantly.

More important is the first pillar, “Wikipedia is an encyclopedia”. This specifies a very constrained kind of literature; an encyclopedia is a summary of already-published knowledge. New users who add personal opinions, personal experience or speculation are told that this is inadmissible irrespective of whether they are right or wrong, because those things are not in scope of an encyclopedia.

If the goal of an article about abortion were to decide “the truth” about abortion, the debate would be unproductive and interminable. In practice, this would not be a shared goal because people would work against each other. Deciding what reputable sources say about abortion, and what opinions are held about abortion by different cultures and groups, is more achievable. There is scope for disagreement, but it is a goal that people with widely different opinions can share.

The drive for quality requires that articles are written in a balanced way, and writing a balanced article usually requires multiple sources and points of view to be represented. This incentivises contributors to write about perspectives that they don’t personally agree with. Paradoxically, the focus on verifiable sources can give the impression that Wikipedia is not interested in or directed towards truth, but this focus actually promotes reliability by directing contributors to reliable sources rather than their subjective responses to the topic.

The right kind of goal

There is another sense in which Wikipedia’s goal of creating a free encyclopedia seems to occupy a “sweet spot”. Explaining this involves looking at two other Wikimedia projects.

Wikisource is a library of free-content texts, including works of literature, reference works, and historically or politically significant documents. It uses crowdsourced effort to upload scans, correct character-recognition errors and proofread. The end product is electronic text that is faithful to the original text of the document or book, organised in a way that makes it useful and findable. Slowly but steadily it has built up hundreds of thousands of documents, many coming from cultural partners such as the British Library or the US National Archives.

Where Wikipedia has to be an original literary work, Wikisource is about replicating texts that already exist. This means that there is a clear measure of progress and fewer possibilities for disagreement. The downside is that there is less scope for creative expression. Contributors do not have the same opportunity to make a personal mark as Wikipedians do when they decide the phrasing or structure for an article.

Wikiversity aims to be a space where people can “mutually cooperate in an active effort to learn”. This includes creating open educational resources, carrying out educational activities (for any educational context or level) and carrying out original research projects. Its tens of thousands of resources cover the whole spectrum of quality. A group of economists at the University of Exeter have shared a handbook of classroom economic experiments through the site, benefiting from textual improvements by the community. This is an example of the site’s very best content: there is a lot more of dubious utility, including fringe points of view.

Wikiversity’s scope is very much less constrained than Wikipedia’s; it accepts a lot of material that would be deleted outright from Wikipedia. It is harder to argue that anything should be deleted, since almost any online materials could have some use in education or research. A project similar to Wikipedia but less constrained might sound like it would attract many more contributions and become a greater success. This is the reverse of what happened. One possible reason is reputation: people are prouder of getting their material onto a platform that rejects a lot of contributions. Another is that there may simply be more demand for didactic encyclopedic text than for other types of educational resource. Another is that contributors need the confidence that their actions will improve the site, and that this requires a tightly-defined scope.

Wikipedia, Wikiversity, and Wikisource’s goals are all laudable, and the differences in their success are due to multiple factors that are technical, historical and social. However, the community’s goal plays a part, and Wikipedia’s much greater contributor base and audience result at least partly from the mix of creativity and constraint.

Summing up

While there are some "do’s" and "don’ts", the success of Wikipedia is not an easily replicable model, and may even be unique. So in most cases it makes sense not to beat them but to join them. Creating a new volunteer community is hard, but moving digital content into a space where an existing community can work on it is easier.[1]

References

- ↑ Masum, H., Rao, A., Good, B.M., Todd, M.H., Edwards, A.M., et al. (2013) ‘Ten Simple Rules for Cultivating Open Science and Collaborative R&D’. PLoS Computational Biology, 9(9) [Online]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003244 (Accessed 17 February 2014).

Gamification

Some computer games have an addictive quality which comes from having many “achievements”, frequently reminding players of their progress. Each new achievement gives a sense of accomplishment for the player, and since the steps are relatively minor, the next reward is just around the corner. The term “gamification” applies when a large task is broken into many relatively minor, achievable goals which are salient in the form of points or trophies. We might ask if successful crowdsourcing requires gamification; for instance, is Wikipedia gamified? The answer is actually not straightforward.

Managing motivations

The attraction of gamifying a task is that it may take on the addictive qualities of a game, getting contributors to put more effort in by making them feel more rewarded. This reward might be a personal sense of achievement or the social value of showing off the badge.

A down-side of gamification is that it can potentially ruin motivation. A person’s motivation can be intrinsic (doing the task for its own sake) or extrinsic (based on external incentives such as pay or prizes). A well-replicated finding in psychology is that extrinsic motivation decreases intrinsic motivation. In other words, if someone is already enthusiastic to contribute, heaping them with prizes and incentives will make them less likely to contribute, or do their best work, in future. Incentives seem to draw attention to themselves rather than to the benefit created by the work. Contributors may come to see themselves as working for the incentives rather than for the good of the work itself and its outcomes.[1]

Extrinsic motivation can also create perverse incentives: when people are rewarded for their number of contributions, or for other achievements defined by the software, the actual quality of the work may be sacrificed. This happened for the citizen science project Galaxy Zoo when it introduced a score and other gamification. When Galaxy Zoo introduced certain game-like elements, like a score, they found that the quality of results dipped.[2]

A forum moderator of the site writes:

In the early days of Galaxy Zoo we did have a ranking system [for top contributor and so on], but it led to people being careless with classifications, unhappy about their position, suspecting each other of somehow cheating etc. So things improved without it.

References

- ↑ Sutherland, S. (2007) Irrationality. London: Pinter & Martin. ISBN: 9781905177073, Chapter 8

- ↑ Shubber, K. (12 September 2013) How Facebook and gaming could help scientists battle disease Wired

Recognition and badging in Wikipedia

Within Wikipedia, three types of "achievements" can get recognition:

- Getting a piece of content (an article or an image) up to a high standard

- A pattern of exemplary behaviour, such as diligent copy-editing across many articles

- An increase in total edits to an arbitrary milestone

Each of these results in badges that users can display publicly, but which are optional.

Content that passes a formal quality review (including Good Article, Featured Article, or Featured Picture) reflects well on the users who create or improve it. Users can add badges to their profile to show which quality content they have been involved with. This helps the user’s reputation and credibility within the site.

MediaWiki software records many measures of user activity: edits to articles, comments to other users and so on. So Wikipedia could have been configured to post a colourful badge on a user’s profile announcing each thousand edits they make, or every hundred vandal edits reverted. Instead, it mostly relies on users voluntarily giving each other badges. Barnstars are informal awards that users can give each other. They reward good work in a particular topic area or good deeds such as reverting a great amount of vandalism. Since Barnstars come from other contributors, not automatically from software, the practice encourages positive interactions between users and a feeling of real appreciation. The positive incentivising effect of barnstars has been confirmed by experiment.[1]

It would be technically possible for these barnstars to automatically appear in a trophy cabinet for each user. In reality, the contributor chooses whether or not to show off these awards. This is how differences in intrinsic/extrinsic motivation is handled: those who want to socially signal their achievements can build trophy cabinets; others who are not interested in awards can treat badges as just a personal message of thanks.[2]

Contributors with a competitive mindset can be extremely productive, so long as they do not interfere with or discourage others. Then again, a project built exclusively around competition will repel the intrinsically-motivated people. Some of the awards internal to Wikipedia direct competitive instincts towards collaboration with others: this is visible in some Barnstars, such as the Barnstar of Diplomacy or the Teamwork Barnstar. Getting articles or images reviewed is partly an individual achievement but requires working constructively with a reviewer and responding to feedback. Hence many of the badges and awards that are available within Wikipedia, along with other initiatives such as mentorship between users, incentivise friendly co-operation. This is not to say that Wikipedia has the ideal mix, since more could be done to make it friendly and welcoming.

Tip: Thanking a contributor

If a user is helpful to you, or improves an area that you want to see improved, a quick thanks may well be appreciated. Wikimedia makes this easy. Every user on any Wikimedia site has a Talk page: its name will begin “User talk:”. The “+” or “Add topic” tab at the top of the page enables anyone to add a public message for that user. Alternatively, the heart icon at the top of the page activates a feature called “WikiLove”: a wizard that makes it easy to give a user a friendly, personalised message or an award. These messages are from one person to another, so it is important to explain in a personal way what you are thanking the user for.

Service Awards are badges users can add to their profiles to recognise a total number and duration of edits. Although it is a rough measure of seniority, edit count is largely meaningless as a measure of quality: an individual edit can fix a typo, introduce a typo, or add ten thousand words of excellent encyclopedic text. The service awards include “Experienced editor”, “Veteran editor” and similar, or alternatively “Grognard Mirabilaire”, “Tutnum”, and similar deliberately ludicrous terms. So depending on their attitudes to their edit count, Wikipedians have three options for displaying their experience as editors: collect service awards, ignore them as irrelevant, or collect silly service awards. As of January 2014, about 500 English-language Wikipedians describe themselves as “Veteran Editors” versus about 100 for the equivalent “Tutnum”.

References

- ↑ Restivo, M., van de Rijt, A. (2012) Experimental Study of Informal Rewards in Peer Production. PLoS ONE, 7(3) [Online]. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0034358 Accessed 17 February 2014

- ↑ Algan, Y., Benkler, Y., Morell, M.F., Hergueux, J. (2013) "Cooperation in a Peer Production Economy: Experimental Evidence from Wikipedia" [Pre print]. Accessed 17 February 2014

Summing up

While contributors appreciate attribution, and can earn status from the quality or quantity of their work, explicit gamification and badging are not essential to successful crowdsourcing. In fact they are potentially disastrous if enforced when the project’s goal is one that contributors already admire, such as free education or advancing science.

Status and badges motivate some people, and creating and awarding badges is an opportunity for creative expression and social interaction. Designed well, badges can direct competitive instincts into collaborative behaviour. Then again, personalities differ: badges that appeal to one contributor might seem offensively infantile to another.

Crowdsourcing in practice

This section looks at some crowdsourcing projects related to research and education and how they illustrate the principles described in earlier sections. The next section will look in more detail at crowdsourcing related to digital media.

Division of labour for a scholarly database

Improving a highly specialised scientific database might seem the sort of task that needs to be kept to experts rather than opened up to the general public. In fact, it fits the earlier description of tasks that benefit from crowdsourcing. It can be broken down into many small, independent steps, each of which can be checked individually, and at least some of the necessary skills are widely available. A crowdsourcing project does not have to leave everything to the public but can invite them to build on something created by professionals.

The Pfam protein families database, used extensively by biochemists, has benefitted from a bi-directional linking with Wikipedia. Encyclopedia articles have been populated with information from Pfam and corrections or expansions can be fed back into it. This puts the Pfam data where it will be very easily found and used by researchers, students and other users, with links to the official site for verification. It also puts any errors where they can be seen and acted upon. The Pfam maintainers realise that minor errors can occur in a large database, but they use that as a reason to make the data as visible as possible rather than as an argument against publication.

Changes to the Wikipedia articles are not copied immediately into the database, but are collected by a script and manually checked. The Pfam maintainers write:

Most edits are simple format or typographic improvements, but many have also provided valuable scientific content, including significant improvements to and expansion of important articles.[1]

With a more controversial topic (such as current politicians) the proportion of vandal edits would be much higher, but protein families are stable enough that anyone editing an article is at least trying to improve it.

So there is a role for the public to play in maintaining a scholarly database. Since “the public” includes highly qualified people, this role is not restricted to low-value contributions. Collaboration between the professional Pfam community and interested members of the public would be impossible to arrange prospectively, but thanks to wiki technology and shared data they can work in parallel.

References

- ↑ Finn, R. D. et al. (1 January 2014) "Pfam: the protein families database" Nucleic Acids Research volume 42 issue D1 DOI 10.1093/nar/gkt1223

Defining progress: geographical data

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is “an open initiative to create and provide free map data to anyone who wants them”. Its maps are built from imports of existing free databases and from individuals using widely available GPS devices and software. OSM presently has one and a half million registered users and about 30% of registered users have made at least one edit. The “Open” means both an open process of gradual improvement and that the resulting geodata is open for use in other web sites and apps.

OSM is not a Wikimedia site and its output looks very different from Wikipedia, but as a community has striking similarities with Wikipedia which underlie its success.

- There is an overarching, easily-understandable goal.

- Existing things such as Ordnance Survey maps can serve as a tangible model of the goal, even though the content of OS cannot be copied.

- The goal allows scope for individual choices and judgements (for instance, in interpreting what it means to document all the features of a particular area).

- There is still a strong limit on individual judgement and hence disagreement (because the map has to reflect real, notable geographical features).

- People may make very different contributions, but the direction of progress is clear. It is verifiable that the map is becoming more accurate and detailed.

- Users retain legal ownership of contributions but apply a free licence (CC-BY-SA and an open data licence) to allow reuse.

- The free licence and hosting by a nonprofit foundation show contributors that they are working for the public good.

- The technology makes each contribution record publicly visible, so people can build reputations. Particularly productive or disruptive users will stand out.

- It is technically possible to insert pranks or hoaxes, but those will be visible to the other contributors and can be undone.

- Coverage is uneven, reflecting the distribution of the required technologies and the interests of contributors.

- If it had waited to be “finished” before being published, it would not exist in a useful form. Releasing the incomplete product to the public has been crucial in getting them to improve it.

- There are leaderboards for contributors and users can build up showcases of badges and awards, but game-like rewards are not central to the site and many contributors ignore them.

As well as encouraging casual users to edit, OSM’s interface also puts a high priority on exporting and reuse. Too much control and scarcity would be counter-productive: the ease of getting data out gives people confidence to put their data in. Free reuse has led to the ubiquity of OSM in ever more applications and devices, which in turn gives the public a stake in its quality.

Motivation: documenting a town

In an ambitious but successful project, a small group of Wikipedians worked with local people, public bodies and businesses to thoroughly document the Welsh town of Monmouth. They wrote articles and shared digital media relating to its history, buildings, notable people, and even individual objects in local museums. This spawned hundreds of articles and over 1000 uploaded images, resulting in about 400,000 hits on Monmouth-created content in one year. The booklet "How to create a Wikipedia Town" summarises their methods and lessons learned.

The motivation for the wiki contributors took many forms. There were competitions to encourage articles and translations, with on-wiki badges and prizes such as t-shirts. While not financially very valuable, the prizes were a tangible sign of appreciation for the volunteers, many of whom were in countries far away. Wikipedia project pages had leaderboards to highlight users who had created or translated particularly large numbers of articles, and examples of the best images submitted.

So the opportunities for recognition and competition were there if contributors wanted the elements of a game, but visibility was not the only motivation. The project’s publicity focused on the historical and political significance of Monmouth, its density of museums and other cultural and educational institutions. It also emphasised the value of free knowledge, of developing skills, and of working online with people from different languages and cultures. The project also showed that everyone in the community could contribute, from the local authority who released digital media under a Wikipedia-compatible licence to individual enthusiasts with computers or cameras.

Monmouth also illustrates the value of open and free content in the sustainability of a project. People are presently encouraged to access the local articles through multilingual QR codes that can be read with a mobile phone, but technology will move on. The main achievement of the project is a great amount of freely-available content in a form that can be endlessly remixed and repurposed. When new location-related technologies arrive, Monmouth will be ready for them because so many of its features are described in Wikipedia articles with embedded geographical data.

Crowdsourcing the restoration and reuse of images

The educational and research value of images or other digital media can be enhanced by additional work:

- restoration (such as cropping, colour balance, removing specks)

- contextualisation (such as embedding a portrait in text about the subject)

- improving metadata (categorising, adding machine-readable information, translating the description into other languages)

Image collections often have content and expertise but not the capacity to do this in detail for every one of their images. So it makes sense to work with a community of volunteers who appreciate such images and care about enhancing them.

Wikimedia Commons hosts the digital media files that are embedded in Wikipedia and the other Wikimedia sites. Its content is freely reusable, either because its copyright has lapsed or it has been given a relevant free licence. It has reached many millions of files, partly as a result of partnerships with museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions. Its purpose is not just to host media but also to enable crowdsourced improvements.

Keeping everybody happy

Not everybody wants images to be restored. Many who want to use an image in a paper or blog post will prefer a cleaned-up version. On the other hand, some researchers are primarily interested in exactly what is removed by image restoration: the texture of the paper, the degradation of an old photograph. Wikimedia Commons' solution to this trade-off is to allow access to multiple versions. This is an example of non-paternalism: giving choices to the user rather than making them on their behalf.

There are two senses in which Commons gives access to multiple versions of a file. A slightly changed file can be uploaded as a new version: the software will show the most recent by default but older versions are still available. "Hyder Khan of Ghazni", shared by the British Library, has nicely vivid colours as a result of digital restoration. The older, unrestored versions are still linked under "File history".

More substantial changes can be uploaded as a separate version with a link back to the original. Freedom to do this comes naturally from the free licences. A major change might be a drastic restoration or it might create a derivative work, for example extracting a portrait of Albert Einstein from a group photo.

Tip: finding source images

Within Commons, images are being edited to make derivative versions or combined to make collages, forming a web of related files. To navigate through this web, use the "What links here" button in the left navigation of any page on Commons.

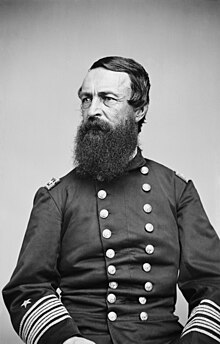

The Commons page for each file shows where the file is embedded on other Wikimedia sites, including Wikipedia. Daily view statistics for Wikipedia pages are also public. This data is all machine-readable, allowing the creation of software tools that track total views of a batch of images. This is how the British Museum can demonstrate more than 27,000 uses of its images across Wikimedia by the start of 2014 and how the Archivist of the United States was able to announce one billion hits during 2013 on the National Archives’ content shared through Wikimedia.

Image restoration

Restoration can include cropping, fixing colour balance, contrast, orientation and hiding damage. It is achievable with widely available software, including free software such as GIMP. This is an ideal task for crowdsourcing.

- The tools and skills are widely distributed, not restricted to institutions

- The task of restoring a batch of images can be broken down into many small steps which do not depend on each other

- The open process means that nothing is lost if someone does a bad job: another restorer can start again from the origina.

- It is publicly verifiable what each user has contributed, so contributors can get recognition for their work

- Involving the crowd does not prevent professionals from doing the work: it just gives the professionals another platform to work on and a chance for more feedback

Volunteers will not work systematically through an entire archive but will pick the images they find interesting or which are most likely to be valued by the wider community. Wikipedia volunteer Durova’s motivation is clear when she writes about restoring a picture of the Wright Brothers’ first flight from an original provided by the US Library of Congress:

This is arguably the most important photograph in aviation engineering history. It’s an honor to work on a version that hundreds of thousands of people will see in dozens of languages.

-

First successful flight of the Wright Flyer, by the Wright brothers – US Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

-

Restored image of Wright Brothers’ first flight – US Library of Congress/ Commons user Durova via Wikimedia Commons

This may contrast with motivations of professionals, who want to get a whole batch of work finished. The trade-off for professionals is that crowdsourcing might speed up restoration of the whole batch, but working efficiently might require them to concentrate their own effort on the less interesting parts of the collection.

Contextualisation

Getting digital content reused in research and education is partly about giving it a useful context, which could be an article explaining its significance, or a worksheet that describes an educational use.[1] Contextualisation is potentially an enormous amount of work, unless you realise that academics and informal learning communities seek photographs, diagrams and other media for their materials. They will provide the context if the media are suitable and if the barriers to doing so are minimal.

Lowering the barriers for these audiences means lowering the legal barrier by giving them permission in advance to copy and reuse: this is what free licensing achieves. It also means putting content where they are looking for it. These are arguments for sharing through Commons in addition to the content holder’s own site.

Wikipedia articles are the clearest example of a context that brings digital media to a large audience, and this is a key reason for sharing material via Commons. Just because an image is relevant to a topic does not necessarily mean it can be embedded in the Wikipedia article. This will come down to the consensus of Wikipedians working on that article about how many images are needed and which have sufficient relevance, technical quality, and aesthetic appeal. If you have a portrait of a historical figure whose Wikipedia article lacks a picture, then there will be no problem adding it. On the other hand, if you have an image related to Henry VIII of England, getting it into that already-developed article is going to require discussion with the article's contributors.

References

- ↑ Poulter, M. (5 December 2013) "What Wikimedia can do for digitised content" Jisc Digitisation and Content Programme blog

Improving image metadata

Once an image is uploaded to Commons, its description and metadata are open for editing by anyone, just like Wikipedia. Possible changes include:

- linking terms in the description to explanations (such as Wiktionary definitions or Wikipedia articles)

- translating the description into other languages

- categorising

- in rare cases: improving or correcting the description

The more discoverable files are on Commons, the more likely they are to be found. So it is strongly advisable to include a full catalogue description and meaningful categories when the files are uploaded. There are Wikimedia noticeboards and mailing lists which can be used to raise awareness of media collections that are being shared.

A set of images shared by the US Library of Congress included one from the aftermath of the Wounded Knee Massacre. That image showed "scattered debris" according to the catalogue description. With the image substantially cleaned up by a Commons volunteer, the "debris" was identifiable as four corpses of Sioux people. The Library's description was updated to reflect this, as was the programme of an exhibition featuring the photograph.

-

Battle of Wounded Knee ‘scattered debris’ – US Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

-

Battle of Wounded Knee, four bodies – US Library of Congress / Commons user Durova via Wikimedia Commons

Other media

Similar restoration and improvement can happen with audio, and free software for editing and clean-up is widely available as it is for images. An example is an interview with British politician Tony Benn which has been cleaned up for use in a Wikinews article, fixing the frequency balance and removing pauses. Commons has relatively little audio content and its requirement for unrestricted formats means that OGG and FLAC audio files are used rather than the more familiar (but patent-encumbered) MP3.

-

Original interview with Tony Benn - Brian McNeil via Wikimedia Commons

-

Edited, cropped and filtered interview - Brian McNeil and User:Symode09 via Wikimedia Commons

Summing up

Restoration and improvement of digital media are ideal applications for crowdsourcing. Wikis and free licensing can connect media collections with remote institutions or hobbyists who want interesting content to work on. Wikimedia Commons offers these benefits as well as the crucial ability to embed media in Wikipedia pages. To get these benefits, content holders need the courage to open up their content and metadata for editing by others.

Further reading

Although aimed at biomedical projects, the rules here are abstract enough to be broadly applicable:

- Masum, H., Rao, A., Good, B.M., Todd, M.H., Edwards, A.M., et al. (2013) ‘Ten Simple Rules for Cultivating Open Science and Collaborative R&D’. PLoS Computational Biology, 9(9). DOI 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003244 (Accessed 17 February 2014).

This article is aimed at experts who want to improve Wikipedia, but many of the points apply to lay contributors and to working with other collaborative communities:

- Logan D.W., Sandal M., Gardner P.P., Manske M., Bateman A. (2010) “Ten Simple Rules for Editing Wikipedia” PLoS Computational Biology. DOI 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000941 (Accessed 17 February 2014).

There are several books about how to contribute to Wikipedia as an individual user. This one is more about the cultural factors that contribute to Wikipedia’s success:

- Joseph, M. Reagle, Jr. (2010) Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia MIT Press.

In this popular book, Clay Shirky looks at crowdsourcing in more depth:

- Shirky, C. (2011) Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age. London: Penguin.

For specific ideas on how academic and cultural projects can work with Wikimedia projects, see the collaboration flowchart created as part of the Jisc/Wikimedia UK partnership.

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

Creative Commons Deed

This is a human-readable summary of the full license below.You are free:

Under the following conditions:

With the understanding that:

|

License

| CREATIVE COMMONS CORPORATION IS NOT A LAW FIRM AND DOES NOT PROVIDE LEGAL SERVICES. DISTRIBUTION OF THIS LICENSE DOES NOT CREATE AN ATTORNEY-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP. CREATIVE COMMONS PROVIDES THIS INFORMATION ON AN "AS-IS" BASIS. CREATIVE COMMONS MAKES NO WARRANTIES REGARDING THE INFORMATION PROVIDED, AND DISCLAIMS LIABILITY FOR DAMAGES RESULTING FROM ITS USE. |

THE WORK (AS DEFINED BELOW) IS PROVIDED UNDER THE TERMS OF THIS CREATIVE COMMONS PUBLIC LICENSE ("CCPL" OR "LICENSE"). THE WORK IS PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT AND/OR OTHER APPLICABLE LAW. ANY USE OF THE WORK OTHER THAN AS AUTHORIZED UNDER THIS LICENSE OR COPYRIGHT LAW IS PROHIBITED.

BY EXERCISING ANY RIGHTS TO THE WORK PROVIDED HERE, YOU ACCEPT AND AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THE TERMS OF THIS LICENSE. TO THE EXTENT THIS LICENSE MAY BE CONSIDERED TO BE A CONTRACT, THE LICENSOR GRANTS YOU THE RIGHTS CONTAINED HERE IN CONSIDERATION OF YOUR ACCEPTANCE OF SUCH TERMS AND CONDITIONS.

1. Definitions

- "Adaptation" means a work based upon the Work, or upon the Work and other pre-existing works, such as a translation, adaptation, derivative work, arrangement of music or other alterations of a literary or artistic work, or phonogram or performance and includes cinematographic adaptations or any other form in which the Work may be recast, transformed, or adapted including in any form recognizably derived from the original, except that a work that constitutes a Collection will not be considered an Adaptation for the purpose of this License. For the avoidance of doubt, where the Work is a musical work, performance or phonogram, the synchronization of the Work in timed-relation with a moving image ("synching") will be considered an Adaptation for the purpose of this License.

- "Collection" means a collection of literary or artistic works, such as encyclopedias and anthologies, or performances, phonograms or broadcasts, or other works or subject matter other than works listed in Section 1(f) below, which, by reason of the selection and arrangement of their contents, constitute intellectual creations, in which the Work is included in its entirety in unmodified form along with one or more other contributions, each constituting separate and independent works in themselves, which together are assembled into a collective whole. A work that constitutes a Collection will not be considered an Adaptation (as defined below) for the purposes of this License.

- "Creative Commons Compatible License" means a license that is listed at http://creativecommons.org/compatiblelicenses that has been approved by Creative Commons as being essentially equivalent to this License, including, at a minimum, because that license: (i) contains terms that have the same purpose, meaning and effect as the License Elements of this License; and, (ii) explicitly permits the relicensing of adaptations of works made available under that license under this License or a Creative Commons jurisdiction license with the same License Elements as this License.

- "Distribute" means to make available to the public the original and copies of the Work or Adaptation, as appropriate, through sale or other transfer of ownership.

- "License Elements" means the following high-level license attributes as selected by Licensor and indicated in the title of this License: Attribution, ShareAlike.

- "Licensor" means the individual, individuals, entity or entities that offer(s) the Work under the terms of this License.

- "Original Author" means, in the case of a literary or artistic work, the individual, individuals, entity or entities who created the Work or if no individual or entity can be identified, the publisher; and in addition (i) in the case of a performance the actors, singers, musicians, dancers, and other persons who act, sing, deliver, declaim, play in, interpret or otherwise perform literary or artistic works or expressions of folklore; (ii) in the case of a phonogram the producer being the person or legal entity who first fixes the sounds of a performance or other sounds; and, (iii) in the case of broadcasts, the organization that transmits the broadcast.

- "Work" means the literary and/or artistic work offered under the terms of this License including without limitation any production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression including digital form, such as a book, pamphlet and other writing; a lecture, address, sermon or other work of the same nature; a dramatic or dramatico-musical work; a choreographic work or entertainment in dumb show; a musical composition with or without words; a cinematographic work to which are assimilated works expressed by a process analogous to cinematography; a work of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving or lithography; a photographic work to which are assimilated works expressed by a process analogous to photography; a work of applied art; an illustration, map, plan, sketch or three-dimensional work relative to geography, topography, architecture or science; a performance; a broadcast; a phonogram; a compilation of data to the extent it is protected as a copyrightable work; or a work performed by a variety or circus performer to the extent it is not otherwise considered a literary or artistic work.

- "You" means an individual or entity exercising rights under this License who has not previously violated the terms of this License with respect to the Work, or who has received express permission from the Licensor to exercise rights under this License despite a previous violation.

- "Publicly Perform" means to perform public recitations of the Work and to communicate to the public those public recitations, by any means or process, including by wire or wireless means or public digital performances; to make available to the public Works in such a way that members of the public may access these Works from a place and at a place individually chosen by them; to perform the Work to the public by any means or process and the communication to the public of the performances of the Work, including by public digital performance; to broadcast and rebroadcast the Work by any means including signs, sounds or images.

- "Reproduce" means to make copies of the Work by any means including without limitation by sound or visual recordings and the right of fixation and reproducing fixations of the Work, including storage of a protected performance or phonogram in digital form or other electronic medium.

2. Fair Dealing Rights

Nothing in this License is intended to reduce, limit, or restrict any uses free from copyright or rights arising from limitations or exceptions that are provided for in connection with the copyright protection under copyright law or other applicable laws.

3. License Grant

Subject to the terms and conditions of this License, Licensor hereby grants You a worldwide, royalty-free, non-exclusive, perpetual (for the duration of the applicable copyright) license to exercise the rights in the Work as stated below:

- to Reproduce the Work, to incorporate the Work into one or more Collections, and to Reproduce the Work as incorporated in the Collections;

- to create and Reproduce Adaptations provided that any such Adaptation, including any translation in any medium, takes reasonable steps to clearly label, demarcate or otherwise identify that changes were made to the original Work. For example, a translation could be marked "The original work was translated from English to Spanish," or a modification could indicate "The original work has been modified.";

- to Distribute and Publicly Perform the Work including as incorporated in Collections; and,

- to Distribute and Publicly Perform Adaptations.

- For the avoidance of doubt:

- Non-waivable Compulsory License Schemes. In those jurisdictions in which the right to collect royalties through any statutory or compulsory licensing scheme cannot be waived, the Licensor reserves the exclusive right to collect such royalties for any exercise by You of the rights granted under this License;

- Waivable Compulsory License Schemes. In those jurisdictions in which the right to collect royalties through any statutory or compulsory licensing scheme can be waived, the Licensor waives the exclusive right to collect such royalties for any exercise by You of the rights granted under this License; and,

- Voluntary License Schemes. The Licensor waives the right to collect royalties, whether individually or, in the event that the Licensor is a member of a collecting society that administers voluntary licensing schemes, via that society, from any exercise by You of the rights granted under this License.

The above rights may be exercised in all media and formats whether now known or hereafter devised. The above rights include the right to make such modifications as are technically necessary to exercise the rights in other media and formats. Subject to Section 8(f), all rights not expressly granted by Licensor are hereby reserved.

4. Restrictions