Basic Writing/Print version

Introduction

editThe authors of this book for the most part are the graduate students in Theory of Basic Writing at Missouri State University. Others are welcome to contribute to the project or to suggest areas overlooked. Future classes in Theory of Basic Writing and current or future ENG 100 instructors will continue the project. This is still open to anyone interested in Basic Writing.

Contents

edit

Part One: Process

Invention

editInvention:

editDetermining the subject and focus of a writing project; the foundation upon which a composition is constructed. Or, in two words or less: idea discovery.

Questions:

editWhat do they want from me?

editMany people begin college composition class assignments with this question, although not many will say it out loud. Well, what do they want from you? First, ask yourself, who is "they"? For many people the only possible "they" is the instructor, but that is not completely true. Behind that instructor is every writing teacher the instructor ever had; the university's general education goals for that class, which can be quite specific; writing theorists the instructor may have read; and of course, the other people in your class who will certainly be reading your writing in peer revision groups. In other words, instead of a single instructor to please, you have an audience.

Luckily, as spokesperson for this audience your instructor has given you a map of sorts -- the assignment sheet. Read this carefully. After reading it, read it again, only this time use a colored marker to highlight key points such as when it's due, page count, type of writing (genre), style (MLA, APA...), and most importantly, anything resembling an ingredients list. If your instructor has given you a bulleted list, you're home free. This is honestly what "they" want.

What if the assignment is vague or uses terms you find unfamiliar? That can happen. What you do then is ask questions, preferably in class when the instructor is going over the assignment for the first time. This may sound obvious, but some students enter college with remnants of the "be cool" attitude left over from high school where sometimes, not always, but sometimes, asking questions was seen as "dumb" or "sucking up" and greeted by eye-rolling or worse by other students. A university is different. Asking questions is what successful students do, and if you have thought of the question, chances are many others in the class have thought of it too and will be grateful that someone spoke up. The instructor will be glad too--questions mean you're paying attention and care whether or not the class goes well for you.

What do I know?

editIn anything that you choose to write about, you will have some sort of advanced knowledge. It may not be much, but it will give you a spring-board to a starting point in your research.

- For instance, if your topic is World War II, think about the key names of leaders and maybe some places involved: Winston Churchill, D-Day, Blitzkrieg. You don't have to know much about a topic, but you can get a start without opening a book if you just think about what you already know. You will probably not know specific statistics or dates at first, but you will know where to start.

- Another topic you might choose is climate change. Think about the key names of leaders and maybe some terms involved: Al Gore, car emissions, the polar icecaps. Again, you don’t have to know much about a topic; you just think about what you already know.

What do I need to find out?

edit- Once you have your general topic—like World War II (WWII), for instance—and you’ve established what you already know about it, then you need to determine what it is you would like to know more about it. Because WWII is too vast a subject to read or write about with any detail for the purposes of your instructor’s assignment, you need to narrow your focus to something more specific about WWII. For instance, you may have jotted down “symbols” when writing down what you already know about the topic. Therefore, you might decide that you want to know more about what kind of symbols were used during WWII and, even more specifically, what kind of symbols were used by the Nazis to mark their enemies. So you look through a book about WWII, or you google “WWII symbols,” and you learn that the colors and shapes determined what the wearer's offense was according to the Nazis. If you decide at this point that you want this to be the specific subject of your paper, then you need to learn as much as you can about the symbols as it relates to WWII, but be wary still that even this topic may be too large for a short paper (i.e. 5-10 pages). Your subsequent research can be narrowed, however, by asking yourself questions like some of the following: When and why were they designed? What was its function for the wearer and the Nazis? What were the different symbols used for? Which symbol was most used and why? and so on. From there you need to decide on a specific question that you wish to answer in your paper, do the necessary research for that question, and then begin the writing process.

- Let's speak to the other sample topic of climate change. You may have jotted down “ozone” when writing down what you already know about the topic. Therefore, you might decide that you want to know more about the ozone layer. So you look through a book about climate change, or you Google “climate change + causes” and you learn by filtering through various sources that may or may not be biased in their reporting.

What is the point of the paper?

editHave you ever seen a preview for a movie that was misleading? You thought you were going to see a movie about guys having an adventure in the wilderness and how they survive only to discover the movie is really a documentary about a family of ants. The disappointment and misunderstanding that follows is what your audience will feel like if your topic is not specific, and if the rest of your paper does not make good on the promise of your introductory paragraph, which should give a clear preview of the rest of your paper.

The point of your paper is to reveal to your audience the details and information about your particular topic. The specific question that you want to answer about your topic will therefore guide your entire paper. The answer is sometimes called a thesis, and much of the writing you will do in university classes is thesis-driven writing. Once you know what your thesis is, you can then make sure that everything in the paper connects to it in some way. The goal is for your paper to look and sound like a crystal stream instead of a muddy ocean. There may be many things that you are interested in discussing in your paper. However, a paper must have one focus (or thesis) to sound clear.

Once you have your thesis, some of the following brainstorming ideas may be helpful to determine what best fits under your topic. Brainstorming will also help you expand the sub-points. Every topic has the option of a variety of sub-topics, but not all sub-topics go together. You need to decide which sub-topics answer the main question that you are trying to answer. Even if you are really attached to a particular sub-topic -- which at some point you will be -- cut it out! Think of it as the bad boyfriend or girlfriend that you can't seem to let go of, yet you know that letting go is the best choice for everyone involved. Break up with that sub-topic and never look back!

Sources of Inspiration

editMany times an instructor will give you the option of choosing your topic for an assignment. This can be a daunting task for anyone. Sometimes having a choice of everything is so big that you end up not being able to think of anything to write about! However, just look around. Something is bound to spark your interest and give you a good starting idea for your assignment. Any of the following can be sources rich with inspiration for topics to write about:

- Media:

- Art

- Literature

- Music

- Movies

- Other Media (i.e. newspapers, magazines, television, internet-browsing, etc.)

- Dreams:

- Your dreams, whether real-life occupational/career goals, personal wishes/wants, or even those you have while sleeping or staring out the window while driving, can frequently contain topics or ideas worthy of writing about.

- Memories/Experiences:

- Thinking about who you are and the experiences that inform your identity can be a fruitful exercise for coming up with writing topics or ways to approach a particular topic.

- Personal Interests: Favorite recent movie: The Martian because I cried at the end of the book and for once the movie got it right. Favorite sport to watch: soccer because I like the agility, speed, and endurance levels of the players. I also like it that it’s not overly violent and it has international appeal. Favorite sport to play: volleyball because I associate it with beaches, summer, family and friends getting together. Favorite TV show: CSI because I learn something every time—it’s the science instruction I never had. I also love it that the main character gets excited about and seems to know everything about bugs. Favorite piece of nonfiction: Brain Droppings by George Carlin because George is hilarious while dissecting the English language, society, and taboo subjects. Favorite popular fiction book: the Harry Potter series because it’s clever and it transports me. Plus, I love it because it led kids to love reading. Favorite Magazine: Entertainment Weekly because I enjoy consuming popular culture during my down time and the writers of that magazine manage to be smart and provocative about pop culture. Favorite kind of music: Lady Gaga because she’s talented musically, and her lyrics connect to my life. Favorite kind of vacation: beach because I like to get up really early and walk on the beach to watch the sun rise, because I love seafood, sea breeze, salt water, sand, sun, breakfast on the terrace overlooking the ocean, because I love dinner on the terrace overlooking the ocean; I love the waves and the unending movement of the seas. Favorite type of food: Asian because I adore all kinds of vegetables, really enjoy hot food, and like the experience of eating with chopsticks.

- Journalling:

- Keep track of your ideas and emotions on a regular basis. These thoughts can be the starting point for an assignment or may provide those extra details needed to make the paper more effective. Through tons of research, keeping a journal has been proven to help your writing for personal or academic papers. Reflecting on things around you as well as things you read and talk about in class will point you in the direction you need to go to improve your writing skills.

- Discussions with family, friends, colleagues, etc.

- Research

- Imagination

- Browsing:

- "Staring down the Spines": Go to the library. Stand amongst the shelves of the topic you are going to write about. Staring at or reading the spines of these books can often initiate an inspiration or two.

Use Pre-writing to:

edit- think more clearly

- establish the beginning of your paper

- keep track of your ideas

- organize your ideas into a conducive paper

- practice expressing yourself in writing

Prewriting/Writing Activities

editThe following are techniques that can aid in the composition process, either in coming up with ideas or in working through various obstacles along the way:

- Listing:

- Listing allows the writer to accomplish several important tasks:

- Finding a topic

- Determining whether you have enough information for a topic before proceeding: After narrowing down your topic, create a list with everything

- Narrowing the topic: If writing about World War II, for example, the focus will need to be on a specific component of WWII or there will be too much information. Make a list of everything you know about WWII. Then decide which topic interests you the most by crossing of those topics that don't interest you as much.

- Example:

- Listing allows the writer to accomplish several important tasks:

| WWII | ||||||||||||||

|

- Free-writing:

- Similar to listing, only in this case you simply start writing in sentence form literally anything that comes to mind in context of thinking about your topic and/or assignment.

- Napping:

- Seriously! Taking a 5-10 minute nap can help rejuvenate the mind and relax you enough to release the tension that comes with writing.

- Meditation:

- Finding a place where you can sit in silence for 5-10 minutes and simply focusing on nothing but your breathing can be a surprisingly effective means of "silencing the noise" in your mind prior to writing, allowing you to better focus on the task at hand without internal distractions.

- Mini-computer games:

- When stuck on a topic or during writing, playing simple but repetitive computer games like Minesweeper can help relax the mind (i.e. it serves as a kind of meditation).

- Outline

- This form of prewriting is geared more toward organization. It groups your thoughts into a definite main point and the supporting detail. So using the topic of "Badges," the outline would being as follows:

|

The thing to remember about outlining is that you can't have a support with only one compliment. If you have an "A." then you have to have a "B."

- Clustering/Brainstorming/Mapping

- Clustering is a primarily visual form of pre-writing. You start out with a central idea written in the middle of the page. You can then form main ideas which stem from the central idea. In this case, you've narrowed the topic down to "Badges." The ideas stemming from that central idea are all having to do with the central idea, but different aspects of that idea. Once the main ideas contain enough information for you to write about, you can determine in what order you will present the ideas in your paper.

- Storyboarding:

- Storyboarding functions in much the same way as Clustering-Brainstorming. It has definite advantages, though. In storyboarding, the ideas are written on note cards in much the same way a Hollywood screenplay is organized. In this instance, you can write information you have gathered about World War II symbols/badges. For instance, say in your research, you find information on rebellions against badges. You can write all of that information on a note card, but make sure you make a note as to where the information came from so that you can easily go back and check your sources and cite them properly. The next note card will cover another topic, say, types of badges and the employment of those badges. The next card can cover the beginnings of their use, and so on.

Why Pre-Write?

editPrewriting for even 5 to 20 minutes can help you establish what you already know about a paper topic, as well as aid you in discovering where you would like to go with a paper (i.e. what you want to know). Doing so can often help prevent you from committing to superficial and/or mundane responses. Prewriting can help you find strong, thoughtful, and clear answers to questions posed by either the assignment or by your consideration of it. It can reveal to you those potential areas of personal interest within the writing task: in a manner of speaking, prewriting enables you to "discover" yourself within the context of your topic. It can also help you nail down responses--to move ideas from short-term memory into long-term or written memory--so that you can get to the work of writing rather than trying to remember what it is you want to say. That is, your thinking is often more clear and better focused when engaged in actual writing. As such, prewriting can act as a tool to stave off or break through what is commonly called "writer's block."

Drafting

editHR Reforms -

Family Cafe HR Reforms, June 2017. Made by: iiWizard_Trist.

Hello. So, Leehongjie the Founder has decided to do our very first, HR Reforms! This will show how much you know about FC and if you really deserve your rank as a HR at Family Cafe. This will be very hard as you guys are HR's so please spend some time on this and answer with long sentence answers. If you do not send this reform to either Me or MissChelsy, new_slates or Bl_0x, you will be demoted.

You will be tested on 4 topics, the same as MR reforms - Stage 1 - Punctuality Stage 2 - Activity Stage 3 - Knowledge Stage 4 - Sessions

Stage 1 Punctuality -

Q1.0 How good is your grammar on a scale of 1-10? 8. I sometimes mess up a lot of times, but I hope I use very good grammar here. Q1.1Have you got the staff card? Yes, I got it on June 6th 2017. Q1.2 Name 3 of your strengths and weaknesses? My strengths is serving customers, helping people, and helping people correct with their grammar. Weakness is not using grammar, and not being helpful (I don't help that much because many MRs/HRs answer the !help. Q1.3 If you were going to be inactive, what would you do? I would message an CEO+ so they could know that I am inactive and when I am back I will see I am fine and not demoted. Q1.4 What is meant by "suitable clothing" in Family Café? If your in the right rank you could get the shirt, for like example I am an MR and an HR Uniform is out, I would like to buy it, but leave it on when I get a Rank HR. Q1.5 Do you have the High Rank uniform? Yes, I do have the High Rank uniform. Q1.6 Improve this sentence: h0ii w3lc0m3 t0 fA3ilY C0FEE WH0TT dO y0UU w0Nt 0n thLs b00tiFU1 D8yy Hi! Welcome to Family Cafe, What do you want on this beautiful day?

Stage 2 Activity -

Q2.0 How active are you from a scale of 1-10? 9. Sometimes I play other games on ROBLOX. Q.2.1 What would you do if a MR was trolling? I will politely tell them to stop, but if they keep on trolling I would warn them, keep on trolling they will be on Warning 2, if they still keep on trolling they will be on Warning 3 and be kicked by an HR. Q2.2 If you found out that a HR AA'ed, what would you do? I will tell them to stop AAing but if they don't I will take a screenshot, send it on Discord and hopefully a CFO+ could come and take away their admin powers. Q2.3 What do you think we could improve the cafe on? Making a lot of updates, make workers work all the time, and serve the correct thing. Q2.4 If we were to shutdown the cafe, what would you do? I would wait until they say it is fine to join back so everyone could be safe. Q2.5 If there was an exploiter with better/higher commands than you, what would you do? I would take a screenshot, send it to Discord and hopefully and CFO+ could see it and I will have permission to ban the Exploiter. Q2.6 Name at least 3 things we do not allow at the cafe. Dating, Advertising, Free Ranking.

Stage 3 Knowledge -

Q3.0 What rank is allowed Mod at the cafe? Board of Directors and up, Q3.1 Who made the Family Cafe Training Center? User Accumalate and Edited by new_slates Q3.2 Who made V2 (Cafe)? I have forgotten, I was here since V2 but I forgot, so I think it was new_slates or Leehongjie Q3.3 Which question is Q8 in interviews? Q8 - Do you have any experience with café genre type of games? That is the Question in Question 8 Q3.4 Who made the Cafe logo? I think new_slates because sometimes he do stuff perfect and the logo is perfect! Q3.5 Name 6 items from the menu at the Cafe. LEE Carrot Smoothie, Cherry Pie, Chocolate Donut, Latte, Frappe, Banana Cupcake Q3.6 Who made our GFX? Probably new_slates, he does a lot of stuff for the cafe so I think new_slates again.

Stage 4 Sessions -

Q4.0 How many sessions do we have each day? Each Day we have 6 sessions. 3 interview sessions and 3 training sessions. Q4.1 What would you do to improve sessions at Family Café I would try to make Sessions earlier and whoever is not has the correct time zone I will tell them when they begin at their time zone. I want to make Sessions earlier because people in different time zones need to sleep like us! Q4.2 How do you record sessions at Family Cafe? You need to have trello and have to be Board of Directors and up, you go to the register board and you will find cards. And it will say dates. Q4.3 What are the times for Training sessions?

Session 1: 10 AM EST | 3 PM BST Session 2: 6 PM EST | 11 PM BST Session 3: 9 PM EST | 2 AM BST Q4.4 If you were to host an Interview, how would you set it out on shout?

Q4.5 How many interviews/trainings have you hosted? (Tell the truth. We can easily check trello) 39 times I have hosted. But I think I Co Hosted like 40 times because I was an MR a lot so yea, Q4.6 What would you do to get people to host sessions more often? [Interviews] Would you like an job here? Go to the Interview Center! The host will be (Username) and the Co Host (Username) Come down to the Interview Center! It would be nice for you to come down get a job and help us!

Introduction to Drafting

editDrafting is writing and drafting is a vital part of successful writing. The reason you will need to use drafting is that it can lay the fundamental framework of your final paper. If you lay the framework well, you'll have a good chance of writing a beautiful paper, however, if you do a poor job on the framework, success could be much more difficult to attain. The following section will take you through the drafting process(es) with instructions and handy tips.

Nobody gets it right the first time

editWhether a writer is the next Ernest Hemingway or a student at any level, drafting must be done as a part of successful writing. If a professional writer says that he/she never writes more than one draft you can pretty much bet they are joking or not telling the truth. Even when writers work to deadline and write at a single sitting, they return to parts of it again and again in order to get it just right. Also, a deadline doesn't always mean done; writers can and do return to an already published piece and revise to make it better.

It does not matter whether the work is a research paper or a poem, all forms of writing need to be drafted. Since a professional writer almost never gets a piece of writing perfect in the first draft, don't feel bad if you need several drafts too. So, if you find yourself very unhappy about your first try at a paper think of it as just the start of something better, i.e. the rough draft. Another advantage to multiple drafts is that the more drafting you do the more chances you have of catching mistakes and improving the paper. This is why it is so important to make time for multiple drafts during the writing process. The time spent drafting will bring you closer to than ever to a more glorious version of your final draft.

The importance of just getting it on the page

editNot much can be done for a piece of writing until it is on paper or computer screen. You may worry that the paper will not be very good or even think that it will be awful, yet you won't really know until you've actually written it. Not only will you and your reader(s) not be able to see what you have written, but there is no chance of working to fix what has not yet been written. For more ideas of how to actually get your words down look at the pre-writing section below.

Pre-writing

editBrainstorming

editBrainstorming is one of the most effective pre-writing techniques you can use. It’s virtually painless and can be pretty fun, if you let it! Brainstorming is easy because there are NO RULES. Let your mind wander and think about things that you would like to explore more. Try to create a mental web of things you can connect to one another. Let the lightning of ideas strike you as they may. Ask yourself a few starter questions such as:

What interests me?

If I choose this subject can I meet the word/page requirements?

Are there other researchers out there thinking like me?

What topics are related to my topic of interest?

What about the topic can I make into a thesis?

Where is there an arguable side of this topic?

Can I see and argue both sides?

What other topics interest me?

Is there anything in the media that I can make into a paper?

How might this affect my daily life?

What kind of examples can illustrate my point?

Is this a fresh/creative topic? Has it become too common?

These questions and others you might create will help you get started on your writing process. Before you even put pen to paper or fingers to keys (If you do have a good idea, WRITE IT DOWN, that way you don’t forget it!). Once you have a topic in mind then you’re ready to move on to the harder stuff.

Free writing

editFree writing can also be pretty fun if you let it. Once you have the main topic of your argument, then it is time to begin getting your ideas on paper. The purpose of free writing is to do just that. Again, with free writing, there are no set rules as to how to proceed. Many teachers will use this technique as a way to jumpstart your creativity and get you thinking. In doing free writing before your paper you will need to write for several (8-10) minutes about your topic. Even if you jump off topic continue writing because you might come back around to the topic or discover a new way in which you might consider going with your topic.

You might want to begin by writing down all the ideas you have about your topic. Write down things you think will eventually serve as your main points. Think about how you would argue with someone who disagreed with your point of view. What would you tell them? Could you back it up with actual evidence? Note: at this point you won’t necessarily need actual evidence, but you will want to have a good idea of the kinds of things out there that you can use to back up your claim.

This is the point where your argument starts to pull together and you will probably find that you have more ideas and points than will ever fit into your argument, but then you can choose the best of the points and make your argument even stronger.

Outlines

editOutlines and rough outlines are where you begin to form the skeleton of your paper. They will be the pattern from which you write your argument. The outline serves as a way to organize you thoughts into a comprehensive process that flows smoothly from one point to another.

The formatting of an outline also helps you to create organization within your paper. Here is an example outline to help you learn the format and organization it will give your argument. I. This is your main topic. It can also be your title. What are you going to talk about?

A. This is your introductory paragraph. Give your intro topic sentence.

1. State your thesis. You should have a clear and developed thesis by now.

B. This is the body of your argument.

1. Main point #1

a. Supporting evidence for main point #1

b. More supporting evidence for point #1

c. Acknowledge and dismiss the other side of the argument

2. Main point #2

a. Supporting evidence for point #2

b. More supporting evidence for point #2

c. Acknowledge and dismiss other side of the argument

C. This is the conclusion of your argument

a. Restate your thesis

b. Summarize your argument

Note: you may have several more main points than this outline has, but they all follow the same basic structure.

Types of Drafts

editRough draft

editA rough draft is a very important step in the writing process. Writing more than one draft gives you the opportunity to catch problems and see where the paper may not be working. So, it is a very good idea to leave yourself with enough time to write at least two or three drafts of your paper. You may want to do an outline to plan your paper beforehand, but doing that is not always necessary. After you get your thoughts, any possible research and or sources needed in order you can begin actually writing. While you write your rough draft you may not feel completely satisfied about the paper, but that's okay because that is what a rough draft is for. You want to give yourself a chance to work to get to the best arrangement of ideas and find different ways of expressing them.

Form: intro, body, conclusion and paragraph

editStart it, say it, finish it--that's an academic writing draft in its simplest form.

Start it. The introduction starts it all. That's where you get the reader involved in what you are writing about and along the way, also get them interested in what you have to say. At the end of the introduction section, many forms of academic writing have a thesis--the main idea or claim.

Say it. Say what you have to say, and don't forget to set up a sequence of ideas that will eventually lead to the conclusion. Each idea or "point" needs room to breathe, so give it its own paragraph, at the very least. Supporting details and examples will also help.

Finish it. The conclusion wraps it all up in a way that doesn't just repeat the thesis--it makes it both bigger and more specific. The terminology for this kind of writing is "synthesis." In synthesis, the whole is greater than its parts, and that is exactly what a good conclusion does.

Needless to say, each part involves using paragraphs, but it's helpful at the drafting stage to think more about "sections." An introduction can be more than one paragraph. A body needs to be more than one paragraph. A conclusion can be one paragraph, but can be more. If your natural tendency when drafting is to move full-steam ahead in one long paragraph with the intention of breaking it up later, it's worth the effort to slow down a bit and make those paragraph breaks as you write. Your draft will be better organized in the long run, a good thing for you and your future reader.

Process: getting started, getting past writing blocks

editAll writers can suffer from those horrible writing blocks, but there are ways around them. If you are having a hard time with the beginning, work on other sections of the paper and come back to the beginning later. You do not have to write strictly from beginning to conclusion. If you have an idea for a certain section write it first. Get that idea out of your head and onto the paper because in doing so, you just might think of a brilliant way to begin your paper. Also, depending on how much time you have to work you may want to take an hour or a day to get away from your paper. Sometimes a little time away from a project can help clear your head and give your ideas more definitions as well as clarity.

Process between drafts: Intermediate drafts, editing, MLA, etc.

editHere the process between drafts is kind of overlapping with two of the other sections, they are, Revising and Editing. Actually, the intermediate drafts are a process of revising your former drafts again and again. You need to look at what you think is not proper or good enough and think of ways that better explain your points to your readers. For more details, you may want to refer to the other two sections about how you could make better draft amendments step by step.

Final draft

editYes! You are coming to the final draft now! However, this is not the end of your final paper yet! The overall structure of the writing construction has already been done, so we could say that you've achieved a half-success! Still, you need to go beyond drafting to the further sections which will be sure to guide you to completion of your paper! Keep up the hard work and you will be glad you went through so many drafts, all that hard work just might eventually pay off in a big way!

Revising

editDefinition

editRevising is re-vision--seeing your paper again. Revising is more than correcting spelling errors, it's finding clarity of thought. It could even be finding new thoughts you didn't have before you started the paper. You might find yourself getting rid of extra fluff.

As you were writing you were revising if you think about it. You had concerns about the paper as you were constructing it. Write those concerns down (make notes in the margin, highlight, make familiar marks) so that you can return to them. Identify what you think are strengths too and bring the rest of your paper to the level you are seeking.

Remember, "A work of art is not a matter of thinking beautiful thoughts or experiencing tender emotions but of intelligence, skill, taste, proportion, knowledge, discipline and industry; especially discipline," according to Evelyn Waugh, 1903-1966, English novelist, travel writer, and biographer.

When to Revise

editYour first draft shouldn't be your final draft. No draft is ever perfect; there's always room for improvement. You have to have content to work with before you revise. You may want to allow yourself to finish a complete draft before you hamper the "creative springs" with revisions. After you have completed drafting your ideas and have established what you consider to be a complete product of the thoughts you intend to convey, then delve into the revision process.

Steps

editRead carefully over your draft several times, with a different purpose in mind to check a specific problem each time (this is where it helps to know your common downfalls with writing). Look first for content (what you said), then organization (your arrangement of ideas), and finally style (the way you use words).

Listen carefully to your paper aloud for confusing statements or awkward wording. Listen for the paper's flow and pay attention to details one idea to the next. Each idea should come to some sort of conclusion while introducing the next idea, and each idea should relate to the one before it and the one after it.

Take time between readings. Allow yourself time to finish a paper (avoid procrastination if possible) so you can put it aside and read it fresh when you go back to it later, to be more objective.

Identify the specific problems with your weaker elements: content, organization, or style. Proofreading of mechanical errors, spelling, and punctuation will follow later.

The essential components of content are the intended purpose, sufficient support, and that all the details are related to the main idea of your paper.

- Achieving the intended purpose--does it provide explanation, details, argument, or narration?

- Providing sufficient support--does it need more detail, facts, examples to support the topic?

- Including relevant details--do you need to cut any irrelevant "fluff" information?

The importance of organization is to arrange ideas and details to make the most effective order, and to connect ideas to show a clear logic of thought process.

- Ideas and details are arranged in the most effective order--ideas and details should make your meaning more clear.

- Ideas are logical and clear--use of appropriate transition words to relay the connection of thoughts (such as "therefore", "for example") and any use of sentence combining techniques.

The power of your style will make the meaning clear, interesting for the audience with purpose, and insure the sentences read smoothly.

- Is the meaning clear--did you use vague or general terms where you need to be precise?

- Is the language interesting, appropriate for audience and purpose--is the language to be formal or informal, did you avoid slang and cliches?

- Is it smooth--did you use a variety of sentence structures?

Four steps to revising: add, cut, replace, and reorder. These are the words you can use in the margin of your paper as you read and make decisions to revise. If you know the standard editing marks you can make revision directly to the writing context. Standard Editing Marks (with additional common writing errors)

Questions you might ask of your final paper:

- Are you saying what you mean to say?

- Will your audience understand it?

- Will it accomplish the purpose?

If you want to be more critical of your writing, judge its readability, clarity, and interest to its audience.

The Recommended Exercises

edit- As you write, keep notes of questionable areas. An easy way to do this is to write the page number and a portion of the line of text that you find questionable.

- Read the paper aloud several times and listen for mistakes. Once you are satisfied with your "read aloud" revisions, ask a couple of other people to read it. You will be surprised by the feedback that you may receive.

- Divide your readings looking for content, organization, continuity, and style.

- Mark your paper where you want to add, cut, replace, and reorder. Sometimes it also helps to get out your scissors and literally cut up your paper into chunks so that you can rearrange at random to see what order looks and sounds best to you.

- Take time between readings. This might mean a short break to eat or walk the dog, for instance, or it might mean a longer break such as returning to your paper in twenty-four hours. Everyone is different. Do what works for you.

- Take time while reading. In other words, take time to reflect on your thoughts. Read one paragraph at a time, envisioning what you intended to say while keeping your audience in mind. Sometimes it is helpful to stare at a blank wall while reflecting instead of staring at your paper or computer screen. This will give your brain a chance for little cat naps, giving it an escape from the chaos of words, information, and eyestrain caused by staring at a computer screen (assuming that you are revising electronically).

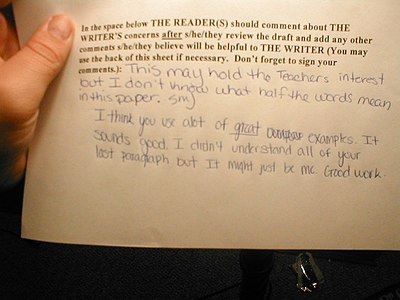

Peer Revision

editPeer revision has added benefits over revising by yourself. Other people can notice things in your paper that you didn't. Some instructors set aside class time for peer review, but even if your instructor doesn't, it's a good idea to seek out feedback from a classmate, roommate, or anyone at all who can offer a fresh perspective.

If you're the one who wrote the paper, make sure you tell your peer what your biggest concern with the paper is. If you need help writing a conclusion, you don't want your peer to spend time circling grammatical mistakes in a paragraph you were thinking about deleting anyway. Remember, your peer isn't just there to catch your mistakes, she might have some ideas about new material you can add to make your paper more exciting.

On the other hand, if you're the one who is reviewing your peer's paper, think about what you'd want in her place. Ask if there's anything she's having trouble with. Be nice, of course, but don't be so nice that you aren't helpful. She may like to hear "Good job," but make sure to explain what you liked about the paper and where you think it could be even better. Remember, it's not about whether the paper is good or bad, it's about how it can be improved.

You have a responsibility to the student whose paper you are reading. Be familiar with the qualities and requirements of the assignment. Consider its merits and shortcomings to provide a complete evaluation and then ask those questions that ask the author about particular segments or certain evidence to support arguments to encourage discussion over the paper.

Possible list of peer revision questions:

- What is the writer's purpose?

- Does the writing include all the necessay characteristics of its particular type (cause-and-effect, narrative, research, etc.)?

- Is the writing organized logically?

- Has the writer used language that enhances her message?

- Is the writing unified/coherent?

- Did you point out the strength(s) or part(s) you found interesting?

- Is there any part that required more information?

- Is there any part that was irrelevant?

- Did you answer any questions the reader had about her writing?

Talking with someone else about your paper will always help you re-evaluate your content. Sometimes it reassures you that you've got it right; sometimes it reveals to you the places that need work. It is always a good idea to share your work before submitting the final draft.

Editing

editWhat is editing?

editEditing is sometimes confused with Revising, or with Proofreading. After you feel you've revised the draft as much as is needed, editing comes into play. Editing involves a number of small changes in a draft that can make a big difference in the draft's readability and coherence. Editing can happen at several points in the drafting process--not just at the end to "fix" things that are wrong. When it comes to writing, it isn't so much about making mistakes that you have to correct. No, there is always an assortment of options, many of which are right. Experienced writers learn which choices fit together well for them, and luckily for you, the secret to becoming an experienced writer is to practice. You can do that.

So, what kinds of things happen when editing? Here are a few.

- word changes

- minor sentence rearrangement

- added transitions

- changes for clarity

- minor deletions

What should I edit for?

editThree main areas that should be addressed in editing are: Content, Structure, and Mechanics.

When editing the content of your writing, it is important to make sure your work has a clear focus or main idea. By asking yourself a few questions, you can avoid incomplete thoughts and/or irrelevant material. The following is a checklist you can use in editing your content:

- I have discovered what is important about my topic.

- I have expressed the main idea clearly.

- I have removed material that is unnecessary, confusing, or irrelevant.

Editing for structure ensures that your ideas are presented in a logical order. A single idea should be represented in each paragraph. Transitions serve to make the relationships between ideas clear. The following checklist is helpful in editing structure:

- My ideas are logically connected to one another.

- Each paragraph deals with only one major idea.

- I have included appropriate transitional words or phrases.

Refining the mechanics in the editing phase prevents the reader from being distracted from your ideas. Grammar and usage errors may be avoided by keeping a dictionary or grammar handbook nearby. A checklist can also help you catch these errors in your writing.

- I have used punctuation marks and capitalization correctly.

- I have checked the spelling of unfamiliar words.

- All subjects and verbs agree.

- I have corrected run-ons and sentence fragments.

- I have used words with the correct meanings in their proper context.

Let's look at a paragraph that is ready for editing.

An editing example

editScrooge McDuck (pre-editing)

editScrooge McDuck is a rich and famous lucky duck that has it all: the luxurious

mansion, 3 intelligent and athletic nephews (and one niece that gets in the way), a global industry in his name that sells anything and everything, and skyscraper sized vault of gold coins, rubies, and iconic bags of money. Scrooge McDuck would have it all if it weren’t for one minute problem. Every other day someone tries to steal his money. People have moved it into the ocean and tried to claim salvage rights. They’ve moved it away with magic, futuristic helicopters, and old-fashioned diesel trucks. Scrooge has researched every possible idea to keep people out of his money bin. Now he needs to

solve that problem once and for all.

This is a pretty good introduction to an essay that's about finding the best possible solution to a problem for a fictional character. However, taking a closer look and making a few small changes could make it even better.

Scrooge McDuck: the Money and the Mayhem (edited version)

editScrooge McDuck is a rich and famous lucky duck that has it all: the luxurious mansion, three intelligent and athletic nephews, and one niece that gets in the way. Owner of a global industry in his name that sells anything and everything as well as a skyscraper sized vault of gold coins, rubies, and iconic bags of money, Scrooge McDuck would have it all if it weren’t for one tiny problem. Every other day someone tries to steal his money. People have moved it into the ocean and tried to claim salvage rights. They’ve moved it away with magic, futuristic helicopters, and old-fashioned diesel trucks. Viewers of Ducktales know that Scrooge has researched every possible idea to keep people out of his money bin. Now he needs to solve that problem once and for all.

An editing exercise

editWord Choice

Sample Sentence: Technology is bad for people.

Edited Sentence: Technology harms our sense of community.

The edited sentence is an improvement because it uses more specific language. We learn that technology is not only harmful, but we also learn what it harms.

Transitions

Sample Sentence: I hated multiplication. I failed my math class.

Edited Sentence: I hated multiplication; therefore I failed my math class.

The transition "therefore" makes a connection between the two thoughts, making the reader see that failing the math class was a result of hating multiplication.

Sentence Structure

Sample Sentence: There was two boys in the hall.

Edited Sentence: There were two boys in the hall.

In the sample sentence, the subject and verb do not agree. In the edited sentence, the subject and the verb agree.

Editing and the Writing Process:

editA major question that students will probably find themselves asking is this: How do I know when to edit a paper? As a matter of fact, there is no simple answer to that question. Writing is a process that involves several steps, and these steps do not always occur in a straight line. Writing any sort of text is a circular rather than a linear process. Writers are rarely completely finished with one step, even after they move onto the next.

Most people tend to think that editing tends to happen sometime near the completion of the paper. In fact, that is not always the case. While the most important part of writing is simply the ability to express yourself and get ideas across, it can sometimes be helpful to take a quick break from drafting or revising and to spend some time editing. Sometimes, playing with word choice, sentence structure, or transitions can help stimulate your mind, leading to new ideas. Thus, it's important to realize that editing is not necessarily a one-step action, but rather something that can be done throughout the entire writing process.

Proofreading

editDefinition of Proofreading

editProofreading is the process of carefully reviewing a text for errors, especially surface errors such as spelling, punctuation, grammar, formatting, and typing errors.

Proofreading vs. Editing

editWhile the terms proofreading and editing are often used interchangeably, they do differ slightly.

Editing is typically completed throughout the writing process—especially between drafts—and often suggests contextual changes that affect the overall meaning and presentation. The focus is on changes that affect style, point-of-view, organization of content, audience, etc.

Proofreading occurs later in the writing process, usually just after the final editing and before the final draft that will be presented for publication (or turned in to a professor). The focus is on correcting errors in spelling, syntax, grammar, punctuation, and formatting.

While some editing will inevitably be done during the proofreading process and vice versa—the writing process is not perfectly linear, after all—focusing on proofreading too early in the writing process is often inefficient because with each revision new errors are introduced. In other words, one does not want to spend a lot of time correcting sentences and paragraphs that may soon be rewritten or even deleted completely.

Examples of Common Errors

editWhile many types of errors exist in writing, there are some that are more common and definitely more noticeable. Some of these errors include spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, subject\verb agreement, and word usage.

A word processor's spell-checker will detect most spelling mistakes. However, if you are writing a paper out longhand, using a good college-edition dictionary can help you prevent many of these mistakes (unless of course, you also can't guess which letter begins the word). If you lack a spelling-bone (I think it's near the funny bone because it is another bone that hurts when it bumps against something), a good strategy to use is to keep a notebook of problem words. You can add words to it each time you have to look a word up in the dictionary, and eventually you will have your own mini-dictionary of words to check more closely. Some people still prefer to do the old grade-school thing and write the word out in longhand twelve times, sounding it out as you write. For example, surprise. Sounded out, it is sǔr (as in Big Sur in California) prise (where the i sounds like a French ee vowel sound, and you can picture yourself being surprised while sipping espresso on the Rive Gauche in Paris. The sound and the image combined may help you remember the spelling.

Punctuation errors most often involve the comma, which means knowing when and how to use one. Of course, that's easier said than done. The comma splice seems to be an especially common error among writers. A comma splice is defined as a sentence that contains two or more complete sentences joined together by a comma. American university professors tend to see it as a major mechanical error. Rumor has it that once in the distant past there was a university in Colorado where any paper with even a single comma splice would receive an automatic F with no exceptions allowed. Hopefully, no extreme cases like that exist now, but avoid comma splices if you're writing for an American audience. If you are in Great Britain, that's another story—comma splices are cheerfully ignored for the most part. Audience truly matters in writing, even on the grammatical/mechanical level.

Although some style guides list nearly two dozen comma rules, there are basically five comma rules you need to know:

- Use a comma with a coordinating conjunction to join two independent clauses. In Layman's terms, fix a comma splice by adding one of the following: and, but, for, so, or, nor, or yet.

- Use a comma to set off non-essential information in a sentence. Basically, put commas around extra information that is not part of the main idea.

- Use a comma in lists or items in a series.

- Use commas in addresses and dates.

- Use a comma between adjectives if they make sense with the order reversed or with "and" inserted in between them.

The Wildcard Rule: There are always exceptions to the rules, and often it is just a matter of personal preference and style. Think about your purpose and your audience; then decide whether or not a comma makes the sentence clearer or is just an extra mark on the page. Sometimes having too many commas is a worse problem than not having enough commas.

Verb tense and subject/verb agreement are also key errors that should be looked for when proofreading a paper. The subject should always agree with the verb in tense and number. These verb issues are often overlooked or unnoticed while writing an initial draft but can usually be caught with a good proofread.

Methods on how to find these verb tense problems, among with other mistakes, will be discussed in the next section.

Strategies for Finding Errors

editIt's often difficult to find your own errors. In this section we will discuss how to look at your own work carefully to spot errors.

The first thing to do is to allow some time between writing and proofreading. Some people recommend letting a text set as long as two weeks before looking over it for mistakes, but that is usually not practical. Instead, try to give yourself at least one full day between finishing your draft and proofreading. In other words, sleep on it. If the deadline is quickly approaching or it is due the next morning, take as much time as you can--an hour or two will do wonders. At minimum, try to take at least take fifteen minutes after the completion of the paper before going back and proofreading. This allows you to look at the same piece of work with a clear eye and a fresh mind.

Second, the paper should be read aloud. Can you make it through without stumbling over anything? Many grammar or word usage errors are not picked up on until the piece is read aloud. Also, have someone else read your work for you (aloud, if possible, so you can hear where the words or punctuation are leading the reader away from your intended meaning). A peer or family member with some distance can also let you know if the progression of the paper needs help, or if something doesn't quite make sense. Do not be afraid to strike out a passage that you thought sounded great, but others are having a hard time understanding.

You can also read the work backwards, one sentence at a time. This helps determine if each sentence, independent of anything else, makes sense. Ask yourself these questions: Are the sentences complete? Does each sentence have a subject (who or what the sentence is about) and a predicate (what's happening in the sentence)? Note which ones need to be changed and why.

Finally, get help! If you're not sure about something, such as the use of a comma or spelling, find a resource or assistance. You can use the writing center at your school, a tutor, the internet, or something as convenient and portable as a grammar book or dictionary!

Common Errors and Correction Strategies

editSpelling

editDon't forget to use your word processor's spell-check feature to identify spelling mistakes. Do a quick visual check for squiggly lines, run the actual spell-check function, and then do a closer check for misspellings or wrong word choices that the spell-checker missed. Although spell-checking is important and should not be skipped, a real-live human can often catch errors that computer software will miss because people are more capable of understanding words in context. For example, spell-check software can't always tell whether their, there, or they're fits in a specific sentence, but a person can always figure it out by looking at the definitions for these homonyms.

Don't forget the low-tech solution: always use a dictionary to confirm any word you're unsure about. Although the built-in dictionary that comes with your word processor is a great time-saver, it falls far short of a college-edition dictionary in paper or CD form. So, if spell-check suggests bizarre corrections for one of your words, it could be that you know a word it doesn't. When in doubt, check a dictionary to be sure.

Punctuation

editThis section will provide useful information on Standard American punctuation: its usage, pitfalls, etc.

Fragments

editBy definition, a fragment is a group of words that is punctuated like a sentence, but that lacks either a subject or a verb. For example: "Full five year warranty and free oil changes!" People use fragments like this in advertisements all the time, but when you are writing for an academic audience, which is far less forgiving of purposeful fragments, your readers may assume that you just don't know the sentence is a fragment. They may conclude that if you got that wrong, you might be wrong about your content too.

So, how can you do find fragments in your own writing? First, find the main verb. Then, find the subject for that verb.

You could correct the example sentence in the following way:

- Original: Full five year warranty and free oil changes!

- Add verb: Receive a full five year warranty and free oil changes!

- Add subject and verb: New customers receive a full five year warranty and free oil changes!

Built-in grammar-checkers are fairly good at spotting fragments, but occasionally go overboard and mark a sentence as a fragment when it is not. Use your own judgment and read each one independently while asking the questions provided above.

Subject-Verb Agreement

editBelow are some examples of errors with subject/verb agreement. Take some time and see if you can figure out what the error is in these sentences.

Original: The dog need to go on a walk.

Revised: The dog needs to go on a walk.

--The subject in the original sentence (dog) is singular. The verb (need) is plural. The verb needs to be changed from plural to singular form in order to agree with the subject.

Original: Chris and Molly goes for walks often in the evening.

Revised: Chris and Molly go for walks often in the evening.

--In this case the verb started out as a singular form. It needed to be changed to plural to fit with Chris and Molly (plural subject).

A quick way to check for subject/verb agreement is to circle the verb and underline the subject of each sentence. Make sure that if the subject is plural, you use a plural form of the verb. If you can not identify subjects and verbs this method will not be practical, and you should seek guidance online, at your school's writing center, or from an instructor first.

One last source for finding tips on correcting common errors is online tutors and workshops. Use internet searches to help you with anything you might be struggling with!

More

editIf it feels like you keep repeating the same words throughout your writing, pull out a thesaurus for ideas on different, more creative choices. A thesaurus can add just enough color and depth to a piece that otherwise seems mundane. Be careful, though, that the word you substitute has the intended meaning. Thesauruses provide words with similar meanings, not identical meanings--so if you are unsure look up the new word in the dictionary!

Proofreading with a Word Processor

editThere are many word processing programs available, and probably the most popular and most commonly used one so far is Microsoft Word. However, with the advent of Microsoft Vista and the lack of easy back-compatibility between new Word and even past versions of Word (including Word from Office 2003), that may change and open source alternatives such as Open Office may gain popularity. That issue aside, one thing all word processors have in common is this: although a word processor is a great tool for writing and includes many special functions that can help a student check for errors such as spelling, punctuation, grammar, repeated words, formatting, and so on, it is not a perfect solution for all problems. When students write, they should be especially aware of the errors the software does not find. This can be a real problem when an assignment is graded for all aspects of the writing process. One of the biggest mistakes a student can make is thinking, "No problem, my word processor will catch all the mistakes for me."

There is no computer program written that can look at every word in context. As great as word processing software is, compared to the human mind it is still extremely limited when it comes to processing language. Even the simple task of spell-checking using a spell-checker tool is not error-free. Although it can find misspelled or unrecognized words, it cannot always differentiate between homonyms. For example, it does not always distinguish between the words to, too, or two. Another problem can arise if your word processor is not set up to correct a certain error. For instance, many spell-checkers are set by default to disregard words in all capital letters because many people do not want it to spell check acronyms. In this case, the word PROOFREEDING would not be caught as a misspelled word because it is in all capital letters.

Despite their many limitations, spelling and grammar-checkers, while not perfect, do help find common errors. However, the best tool that you can use to spot errors is your own eye. Spend the time to look over your writing carefully to make an honest attempt at turning in that elusive error-free paper, AKA by editors as clean copy.

Proofreading Examples

editIn the earlier section about proofreading using a word processor, it was mentioned that although software can correct spelling errors or alert you to unrecognized words, it cannot distinguish between words that sound alike (homonyms). Take a look at the examples containing misspelled words below and see if you can find the wrong word in each sentence. Although there are no spelling mistakes, each sentence does contain a mistake in word usage.

- What will today's students listen to when they are in their 40s? Is disco music in there future as well?

- Coach Thompson's team won ten consecutive Big Twelve Conference crowns, and tied the NCAA record with nine consecutive NCAA champion from 1978-1986.

- Life experience sometimes plays an important roll in how and what a student may write about.

- During the parade, they band members marched in unison.

- Do you think computers have changed are everyday life?

- The store at the end of the block does not except checks any longer.

- One study showed that of the countries 250 million people, almost 10% still smoke.

- As evidence has shone, the crime rate in the city has dropped in the last decade.

- If writing is such an important part of the school curriculum, than why are so many students having problems with the essay assignment.

- I was raised in a home were rock and roll music was not allowed.

By understanding that proofreading requires a slow, deliberate analysis of what you have written, you will be able to recognize the trouble with the sentences above, and be better prepared to recognize the same type of problems in the future.

Corrections and commentary for the above examples

edit- What will today's students listen to when they are in their 40s? Is disco music in their future as well? "There" should be "their" because the second form shows possession. It is their future because it belongs to them.

- Coach Thompson's team won ten consecutive Big Twelve Conference crowns, and tied the NCAA record with nine consecutive NCAA championships from 1978-1986. "champion" should be "championships" because champions win championships. The former refers to the players, the latter to the titles they hold.

- Life experience sometimes plays an important role in how and what a student may write about. "Roll" should be "role." The first "roll" refers to the verb roll or the rolls you eat at Thanksgiving, someone's role is the part they play in something.

- During the parade, the band members marched in unison. "They" should be "the," and is a common typo--the type that suggests sloppiness on the part of the writer, nonetheless.

- Do you think computers have changed our everyday life? "Are" should be "our." Although some people pronounce them alike, "are" is a verb (a form of be) while "our" shows the possession of a group. (People are busy during the holidays. Our family still manages to get together.)

- The store at the end of the block does not accept checks any longer. "except" should be "accept." "Except" forms the base for the word "exception" and shares a similar meaning; "accept" forms the base for the word "acceptance" and shares a similar meaning.

- One study showed that of the country's 250 million people, almost 10% still smoke. "Countries" should be "country's." "Countries" is the plural form (i.e., more than one country); "country's" is the possessive form and shows that something belongs to the country.

- As evidence has shown, the crime rate in the city has dropped in the last decade. "shone" should be "shown." "Shone" is a form of the verb "shine," while "shown" is a form of the verb "show."

- If writing is such an important part of the school curriculum, then why are so many students having problems with the essay assignment? "Than" should be "then." "Than" shows relationship when comparing two things, while "then" shows a time relationship. Ex: First I went to the store. Then, I went home.

- I was raised in a home where rock and roll music was not allowed. "Were" should be "where." Were is a form of the verb "be," while "where" indicates a location or speech.

Narrative and Memoir

edit"whay an interesting book it is!I wish i would borrow early book earlier"

Creative Writing

editWhile other forms of writing ask that you to find research in external source before you begin, creative writing does not require this of you. More often than not, creative writing projects only require you to use your memory and imagination to tackle your project. This ability to just sit down and write without having to perform research allows you to practice writing whenever you want. You can try writing a poem on your coffee break or during a bus or subway ride. You can spend an afternoon writing a memoir about your favorite childhood pet, or you could begin to keep a journal where describe the events of your day, the weather, the books you are reading, or television shows you like to watch. For creative and personal writing, the possibilities are endless.

Now you may be asking yourself if you have anything worth writing about, and the simple answers is yes you do! Every day provides an infinite number of topics to write about, whether that be having dinner with a friend, the taste of your coffee, or the beauty of a painting you saw in a museum. The activities in this section will help you jump-start your creativity, and before you know it you will have written some great poems, short stories, and memoirs.

Poetry

editMore so than any other form of writing, poetry is known for its ability to express ideas and emotions or tell stories using very few words. Though some poems can be long, in general the best poems are those that help us appreciate mankind and nature by condensing a scene or event into short poem full of specific details. With these poetry exercises, you will attempt to write poems that are short but specific. Like every other kind of writing, the most successful pieces of poetry help us clearly imagine what the poet is talking about by using concrete images or facts. The following exercises will also help you practice writing clear sentences, think about grammar, and practice using punctuation, but most of all have fun writing.

Poetry Without Punctuation

editHave you ever got tired of having to use punctuation and wish you could write without having to worry about periods, commas, and quotations? Well many poets have become famous for writing pieces that do not use any punctuation to make their sentences clear. However do not be fooled, writing without punctuation can be just as difficult as writing with it. For this exercise, read Lucille Clifton's "the garden of delight" and then write a poem about a garden or park you like to visit without using any punctuation. Keep in mind that you want the reader to be able to easily understand the poem, so like Clifton insert line breaks or spaces to help the reader understand how to read the poem.

Then on a separate piece of paper, try writing the same poem again, but this time use punctuation. Notice how the poem changes and the punctuation can help you. After you have written the second version of the poem, spend a few moments and journal about writing both poems. Which poem was easier to write? What made it easier to write? Do you like this poem better and why? Which do you think is easier for the reader to understand? Why? Be sure to have both poems in front of you when you journal so that you can easily compare them, noticing where you used punctuation in the second poem and how that might or might have clarified what you wrote in the first poem.

Narrative and Memoir

editDefining Narrative and Memoir

edit- Narrative:

1.ACTION 2.REACTION 3.DIALOGUE these three must be used when writing a memoir (narrative lead)

Simply stated, narrative is a style of writing that tells a story. It can be fiction or nonfiction and is typically told from a first- or third-person point of view. Narratives can be in the form of short stories, poetry, personal essays, novels, monologues, folktales, fables, legends, etc. The characteristic hallmark of narrative is that there is a character or voice telling the reader or viewer "what happened," as with the "narrators" of most novels and short stories, and many movies or television programs. Well-known and popular TV examples of this would include the late 1980s/early 1990s drama, The Wonder Years, or more recently the prime-time shows Scrubs, and Desperate Housewives. A narrative may or may not have dialogue, depending on whether or not the event or action taking place is simply an observation from a distance (like the narrator of a nature documentary) or, for instance, a kind of I said or he/she said situation (like J.D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye and F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby). Some narratives have multiple narrators, or more than one character/voice, each of whom is responsible for either telling one part of a larger story, or who tell different versions of the same story. Several narrative examples of the use of multiple narrators can be found in William Faulkner's novel The Sound and the Fury, Ernest J. Gaines's novel A Gathering of Old Men, and Akira Kurosawa's film Rashomon.

- Memoir:

Memoir is a specific type of narrative. It is autobiographical in nature but it is not meant to be as comprehensive as biography (which tells the entire life story of a person). Instead, a memoir is usually only a specific "slice" of one's life. The time span within a memoir is thus frequently limited to a single memorable event or moment, though it can also be used to tell about a longer series of events that make up a particular period of one's life (as in Cameron Crowe's film memoir Almost Famous). It is narrative in structure, usually describing people and events that ultimately focuses on the emotional significance of the story to the one telling it. Generally, this emotional significance is the result of a resolution from the conflict within the story. Though a memoir is the retelling of a true account, it is not usually regarded as being completely true. After all, no one can faithfully recall every detail or bit of dialogue from an event that took place many years ago. Consequently, some creative license is granted by the reader to the memoirist recounting, say, a significant moment or events from his childhood some thirty years or more earlier. (However, the memoirist who assumes too much creative license without disclosing that fact is vulnerable to censure and public ridicule if his deception is found out, as recently happened with James Frey and his alleged memoir, A Million Little Pieces.) Furthermore, names of people and places are often changed in a memoir to protect those who were either directly or indirectly involved in the lives and/or event(s) being described.

Common Approaches

editBelow you will find some typical writing prompts that will allow you to begin writing a narrative or memoir. Remember to stay focused and to tell a story when writing in this genre.

- "Write about someone significant in your life."

- "Write about the worst/best, most significant/exciting/boring day of your life."

- "If you had a chance to talk with a historical/famous/legendary/etc. person, what would you talk about? Explain why."

Sample Assignment

editThere is not one right or best way to write a narrative or memoir. However, there are certainly better ways to write in this genre than others. Read the following short samples of an "excellent," "needs a little work," and "needs a lot of work" narrative writing assignment! Because it should be a narrative, remember that the writer should be telling a story. All grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors should be cleared up when editing. See Basic Writing/Editing for more help. So the focus will be on content.

Assignment: "Write about someone significant in your life."

Needs a lot of work:

My mom is a significant person in my life. She has always taken good care of me. She looks after my family and does a lot of hard work. My family couldn't make it without my mom. I really love my mom a lot because of all she has done for me. She's a great person. I tell my mom everything. She is probably my closest friend.

*This narrative needs a lot of work. There are very few specific details. Questions that need to be answered are: How does she take good care of you? What kind of hard work does she do? Why is she a great person? What kind of a person is she? What does she do with the information you give her? What kind of sacrifices has she made for the family?

Answering these questions will really improve the writing. The audience wants to know as much interesting information as you can tell them about this topic. Think about all the details you see and hear in a movie or really good book. You don't need to reach that level, but that should be your goal. Giving some specific, personal examples will help the audience understand the writing and enjoy reading it. See the next example for a better response to this assignment.

Needs a little work:

When I was young, I didn't get along very well with my mom. We used to fight a lot and I just didn't understand her. She always seemed to be in my business and trying to snoop around. I've always had really dry eyes. Sometimes they water to compensate or get really red because they're so dry. My mom used to think I'd been crying and bug me to death asking me if someone had hurt my feelings at school! I was a teenager!

But now me and my mom are best friends. I tell her everything and she tells me everything. Sometimes we still disagree, but we've learned to understand and respect each other. We're very different people, but I don't know what I'd do without my mom. She has always supported me and stood behind whatever I've wanted to do or be. She's my biggest fan. In my mom's eyes, I could be the next great world leader, or a famous ballerina, or the first astronaut to live on Mars. It took me a while to realize just how significant my mom is to me, but now that I know, nothing will ever change the way I feel about her.

*This narrative is better than the first one because it has more details and gives some specific examples regarding the writer's relationship to her mom. However, it still needs a little work because even more details could be provided to give the reader a clearer picture of their relationship. For example, the reader doesn't know what has changed in this relationship that led to the two of them becoming like "best friends."

Excellent:

When I was a teenager, I didn't get along very well with my mom. It seemed like we fought on a daily basis and we rarely if ever understood where the other was coming from. I felt so separate from her and it was impossible to tell her about my problems because all she would ever do is freak out.

I remember one particular fight in perfect clarity. We were having one of our good days - that should've been the first warning sign. I was helping her weed the flower beds, telling her about a conversation that I had had with my boyfriend's mom the previous night. When I was finished telling her about the advice that Janice shared with me about how to reconcile with a friend of mine, my mom grew very quiet. I asked her if something was wrong but she continued to stare at a stubborn dandelion in the middle of her peony bed.

Finally, she looked up at me. Frustration and anger filled her face and tears spilled down her cheeks. "How come you never come to me anymore?" she spat. "Why do you have to go to other moms to talk about your problems? Am I not good enough?"

I didn't really know what to say. I tried to reason with her, explaining that it's normal for teenagers to talk to other parents about personal problems, but all she did was storm off.

That was the day that I realized how much my mom actually meant to me. I knew from her reaction that she felt devalued and even though we had our issues, I also knew that I had a great mom. She had always taken care of me, provided for me, and as a young child, she was my best friend. I wanted that back and from that day on, the two of us worked on communicating better and getting to know each other all over again.

*This is an excellent example of a narrative because it provides necessary details to help the reader understand the relationship between the mother and daughter. In the "needs a little work" example, the writer did not explain how the mom and daughter became "best friends." This is an important and significant detail. It is important to explain the important details as much as possible in a story. To continue this writing, the writer will probably give another example of how things were after they began to understand each other better. This will give the audience a clear picture of the progress of the relationship.

Examples:

editThe following are example compositions written for an assignment where students were asked to write narrative descriptions about a day they consider to be one of their worst. (Note: Even though two of the following three examples have death as a theme, personal narratives and memoirs can just as easily be written about smaller, less dramatic events from one's life.)

Example 1:

It was the worst day of my life, and it was only 10:00am. Sitting in my dorm room sobbing into the phone, my mom tried to calm me down. But she couldn't erase the pain and misery, hurt and disappointment I was currently feeling. What had gone wrong? Why was everyone against me? How would I get through the rest of the day... the week with my injuries? Let me start from the beginning.

It was a cold, blustery day at Evangel University. I had spent the last few days preparing for a presentation for my Children's Literature class, and I would soon go to the preschool just down the road to teach a lesson for the preschoolers. I had made beautiful little magnetic snowflakes that the students could take home with them. The snowflakes went along with the story I'd be reading in about an hour.