Open Education Practices: A User Guide for Organisations/A word on ICT

In a recent editorial of n+1 magazine the authors posit Webism as a social movement, as significant as feminism, perhaps even socialism (The Internet as Social Movement, The Editors, 2010). Theirs is an historical and political overview of the way the Internet has changed the way information is created and presented, such as the manner in which the traditional printed book has been subverted. Their argument is that people mistakenly think of the Internet, and all the technology that goes with it, as simply tools, when they are more accurately an evolving social phenomenon. Regarding the book's displacement by the Internet, they say, "At this point the best thing the web and the book could do for one another would be to admit their essential difference. This would allow the web to develop as it wishes ...." (The Internet as Social Movement, The Editors, 2010).

These pages are intended to stimulate critical thought and discussion about Information and Communication Technology, and whether it is enabling a social movement. Perhaps we could start this discussion with a consideration of what literacy means today, and how the choices we make in tools, and policies we use to govern practice with those tools, affect those have on the development of that literacy.

Digital literacy edit

How it affects teaching practices and networked learning futures - a proposal for action research.

The following is a critique prepared by Leigh Blackall and originally published in The Knowledge Tree in 2005. In this critique the author considers how digital literacy affects teaching practices in Australian education. For example, understandings of digital literacy, the impact of open source software and the place of content within the worldwide rapid publishing and networked learning revolution (Web 2.0). Participatory action research is suggested as an approach to developing awareness of new models for online learning, improving digital literacy skills and enabling networked learning practices in the education sector.

The tone and direction of this critique is determined by consideration of:

- the tension between an understanding of literacy based on print traditions, and an emerging understanding of literacy based on Information, Communication Technology (ICT), or digital literacy,;

- migration to free and open source software and courseware within the Australian education sector and the subsequent impact that may have on levels of digital literacy, including access and equity;

- the influence that the 'content is king' period (1998–2004) has had on the collective thinking about online teaching and learning in Australia, and the impact it is having on networked learning possibilities;

- the broader picture of the Internet and the World Wide Web, specifically concepts of Web 2.0 and the influence it may have on online teaching and learning practices;

- a proposal to initiate action research projects to investigate digital literacy and networked learning futures in Australian education.

What is digital literacy? edit

It is commonly held that having an ability to read and write impacts considerably on a person's potential to communicate and learn. But how, and in what ways does a person's ability to read and write digitally, impact on that potential? Being able to access the Internet; find, manage and edit digital information; join in communications; and otherwise engage with an online information and communications network, are arguably aspects of what could be called 'digital literacy'.

At present Australia measures literacy (consistent with International practice) based on "... how well people use material printed in English. Progression along this continuum was characterised by increased ability to 'process' information (for example to locate, integrate, match and generate information) and to draw correct inferences based on the information being used" (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 1997: para. 13).

Recent publications, looking at technological impacts on education, suggest that there are important forms of communicative literacies that go beyond text and print. For example:

- Many students are entering their school or college with multiple literacies that go beyond text, and this trend will strengthen over the coming years. Educators will need to acknowledge and recognise these new literacies, and build upon and extend them (Australian Capital Territory Department of Education and Training (ACT DET), 2005: para. 12)

- 21st century literacy is the set of abilities and skills where aural, visual and digital literacy overlap. These include the ability to understand the power of images and sounds, to recognize and use that power, to manipulate and transform digital media, to distribute them pervasively, and to easily adapt them to new forms. (The New Media Consortium, 2005: para. 2)

There is an emerging belief here, that a person's ability to process digital information is an important factor in the consideration of literacy. What then is the new scope for measuring literacy if we accept that information and communication technologies are affecting people's ability "... to locate, integrate, match and generate information" (ABS, 1997: para. 13).

A definition of digital information literacy has emerged from recent research into the capability of participants in tertiary education in New Zealand (See Hegarty, Penman, Kelly, Jeffrey, Coburn, & McDonald, 2010).

A Definition of Digital Information Literacy edit

Digital Information Literacy (DIL) is the ability to recognise the need for, to access, and to evaluate electronic information. The digitally literate can confidently use, manage, create, quote and share sources of digital information in an effective way. The way in which information is used, created and distributed demonstrates an understanding and acknowledgement of the cultural, ethical, economic, legal and social aspects of information. The digitally literate demonstrate openness, the ability to problem solve, to critically reflect, technical capability and a willingness to collaborate and keep up to date prompted by the changing contexts in which they use information.

Issues affecting digital literacy in Australasian education edit

Digital technologies and networked communications are still very much in development. Past, present and future changes in protocols, standards, operating systems and software platforms, not to mention market, infrastructure and policy directions, have, and will inevitably, change - radically impacting people's motivation to sustain effective digital literacy.

The following are four major issues affecting the development of digital literacy in Australian education.

The adoption of Free and Open Source (desktop application) software in Australasian education edit

While the use of proprietary desktop software is still very prevalent in Australian and New Zealand educational organisations, there has been a notable shift by government organisations around the world to acknowledge the financial savings and Information Communications Technology capacity building benefits that free and open source software (FOSS) offers. The United Nations Education, Social and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has been documenting this shift around the world, including the eagerly awaited report from the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA) which found that schools using FOSS spent between 20 and 60 percent less on ICTs than non-FOSS-using schools (BECTA, 2005)

Australia has produced its share of publications looking at the use of FOSS in the education sector with earlier work stating that "... the use of open source software across Australian schools and sectors tends to be idiosyncratic and piecemeal rather than coordinated" (Moyle, 2003: para. 30).

Since then there has been an increase in the use of FOSS in Australian and New Zealand education.

The Northern Territory Department of Employment, Education and Training has adopted Linux and other FOSS, and there have been numerous incidents elsewhere in Australia of a migration to FOSS server applications, such as the course management system Moodle (as used by the Education Network Australia). In the case of the Northern Territory's adoption of Linux and other FOSS applications, the following figures were reported to the Open Source Industry Australia. The decision to use Linux and OSS saved the Northern Territory Department of Employment, Education and Training $1M in the first year, and allowed it to put 1000 more workstations into schools (OSIA, 2004).

Regarding FOSS uptake in Australia/NZ schools, Moyle (2004) in a later paper states:

- Schools around Australia and New Zealand are experimenting with and deploying open source software in a range of different ways. Although there are no formal measures available, it seems from anecdotal evidence that this use is growing (Moyle, 2004: para. 14).

In New Zealand recently, Warrington Primary School adopted and self managed FOSS across its school and community computers in 2008. However, the NZ Ministry of Education rejected the schools requests to retain the financial savings for other school expenses (Hedquist, 2008).

Financial savings and long term IT capacity improvement - through the use of FOSS, open standards and more versatile desktop applications - has been shown to be considerable at an organisational and departmental level (BECTA, 2005). But what of the benefits to individual staff, students and subsequently the communities they serve? Case studies of educational organisations in other countries that have attempted to migrate from proprietary to FOSS desktops have strongly indicated that there are substantial challenges - mostly to do with staff and older students being accustomed to the proprietary desktop setup, supported by community tolerance for pirated software (van Reijswoud & Mulo, 2004).

If educational organisations developed procedures that are more supportive for using free software, then an individual's option to use free software would become a more viable consideration, as their choice to do so would not mean compromising interoperability with the school or college system. Opening such an opportunity, within a supportive educational environment, translates into an investment in access, equity and digital literacy oriented educational practice. This of course begins to address another issue - the pirating of software by staff and students within the organisation who are trying to remain compatible to the organisation's choices in software (van Reijswoud & Mulo, 2004). With appropriate levels of encouragement and support from the organisation, the long term benefits of free software at an organisation and departmental level could be foreseeable, through the gradual development of skills and digital literacy amongst its staff and students.

While the shift in thinking around the world towards the use of free software is notable, and the benefits to education are measurable, sadly, it has been difficult to access information on strategic approaches to FOSS in the various State and Federal Departments of Australian and New Zealand education. Very few examples were found of policy-enabled support for training and professional development within the schools and colleges on the use of free software. Given this apparent lack of Departmental support or direct financial incentive for schools and colleges to use free software, teacher training and professional development programs within educational organisations are likely to continue their ICT training strategies based on proprietary desktop software, and perpetuating the limitations of people's ability and willingness to use free software.

Broadening the scope of the organisation's software training and support capacity beyond the current narrow scope of proprietary software, would create opportunities to broaden the digital literacy of staff and students, including their awareness of social and educational issues affected by computing, such as access and equity, and develop opportunities to implement alternatives to commercial and/or pirated software.

The 'content is king' era in Australian education edit

As is indicated by the Australian Capital Territory's Department of Education and Training (ACT DET), 2005 recent report on emerging technologies, there is still a big focus at a Departmental level on content centric models of online teaching and learning. While the ACT DET report acknowledges some of the newer models for online learning briefly covered here and otherwise known as networked learning and open education, a great deal of this phenomenal report focuses on what might be termed 'eLearning 1' - the content centralised, closed, learning object model to online learning.

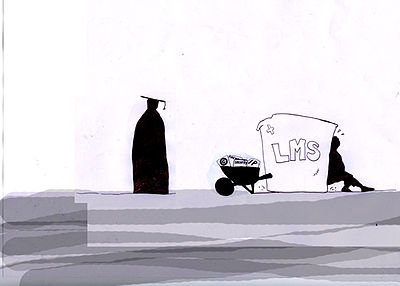

Departments and organisations have invested staggering amounts of money in this model. NSW's TAFE Connect project, Australian Flexible Learning Framework's Toolboxes, and the Le@rning Federation's Online Curriculum are examples of large scale investment in such a model. Much of the content produced has been designed to work within and (theoretically) across a number of Learning Management Systems (LMS), spawning further content related projects such as research into reusable learning objects, digital [copy]rights management, and meta data tagging. In the face of a proliferation of freely accessible content through the social media networks, it begs the question if these investments are of benefit to teachers and learners. In fact it was argued as early as 2001 by Andrew Odlyzko and David Wiley, that the LMS, content centric model is not beneficial to teachers and learners, or an effective strategy for online teaching and learning, and reiterated on by other authors (e.g., Blackall, 2005; Downes, 2005; Hotrum, 2005; Farmer, 2004; Parkins, 2004; Seimens, 2004).

Downes (2005) spoke about an inevitable shift away from closed-content/centralised/managed learning, to a more open/decentralised/individual model, based on trends in open network Internet usage. Downes used the emergence of the Web 2 phenomenon to illustrate this alternative, demonstrating the interoperability of open network services and arguing that it makes very little sense to remain with the content centric and firewall protected model, and that we need to instead embrace more open, distributed and networked learning models (Downes, 2005).

This shift in thinking from a content centralised model to a dispersed networked model is certain to generate tension not only between teachers and their departments, but between teachers and students. The differences and power shifts between the two models are deep, some (Downes, 2004; Seimens, 2004; Illich,1970) would even suggest that we are waiting for a paradigm shift in educational ideology.

The likely shift away from centralised models to decentralised networked models will necessitate a more independent level of digital literacy among teachers and learners. Educational organisations may have to consider more substantial initial investments in broad scoped literacy programs to lift the level of digital literacy, something that could perhaps be paid for by a reduction in content creation and an increase in the use of free software.

Web 2.0 and world wide networked learning edit

Never before has it been easier to create and publish digital media to the Internet. Not only is it easier, but it is conceivably free, so long as a person has access to a networked device. No longer does a person need to know complex html coding, ftp, or how to manage servers etc. Thanks to a myriad of free web based services, a person can create, publish and manage their own content without the need to employ experts or use complex software. This revolution in online communications has triggered an explosion of content creation, much of it licensed to Creative Commons (Linksvayer, 2005) – resulting in a vast range of digital content created by popular participation online, freely available for reuse under Creative Commons Licenses, and ever evolving. This change in the nature of information, communication and knowledge has been dubbed Web 2.0 (Boyd, 2005). It signifies a fundamental change in the nature of the Internet, content ownership, and information dissemination.

The visionary creators of the Cluetrain Manifesto recognised this change as early as 1999 when speaking of markets in the broadest possible sense:

- Networked markets are beginning to self-organize faster than the companies that have traditionally served them. Thanks to the web, markets are becoming better informed, smarter, and more demanding of qualities missing from most business organizations ( Locke, Searls, Weinberger, Levine, 1999: para. 1).

Educational organisations (redefining themselves more and more, for better or for worse, as business organisations) are struggling to position themselves in the Web 2.0 era. Arguably their heavy investment in the centralised, proprietary based, content centric model, typified by the LMS, has made it extremely difficult for organisations to make a change, largely because networked learning does not require such an investment.

As Harold Jarche put it when he joined the online discussion between leading educational bloggers on the concept of ’Small Pieces Loosely Joined’ (distributed networked learning), and echoing the concerns of earlier writers (Downes: 2004; Odlyzko, 2001; Wiley, 2001).

- This is still a difficult message to get past many educational institutions and training organisations. You don't have to spend a lot on the technology. You need to focus on getting the people and processes aligned so that learning happens. Save the money that you would spend on an LCMS and put it into the time to let people develop processes that work for their unique contexts. (Jarche, 2005: para. 4)

Many schools and teachers have not yet recognized—much less responded to—the new ways students communicate and access information over the Internet. Students report that there is a substantial disconnect between how they use the Internet for school and how they use the Internet during the school day and under teacher direction. For the most part, students’ educational use of the Internet occurs outside of the school day, outside of the school building, outside the direction of their teachers (Levin, Arafeh, Lenhart & Rainie, 2002: para. 3).

Anya Kamanetz, author of the book DIYU: Edupunks, Eduprenuers, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education, noted a recent survey of US universities that revealed that on average 82% of faculty never use social media in their work! Whereas 72% regularly use closed Learning Management Systems (Kamanetz, 2010).

Australian educational Departments and organisations, as do other sectors affected by the changes in media and communications, need to start accepting that there are considerable cultural changes taking place around them that are affecting the fundamental understandings with which they operate. Educational departments and organisations would do well to begin implementing exit strategies from previous content centric models of online learning (Morrison, 2005), and start investing in digital literacy programs and sustained participatory research. The goal should be to set in motion a continuous and sustained development cycle focused on enabling, supporting and encouraging the use of free software, social media, open education and research and networked learning practices.

A proposal for a participatory action research edit

Developing better digital literacy skills and awareness of new models for online learning in Australian education

The New Media Consortium (2005) outlined five strategic priorities for creating change to enable "21st Century literacies":

- Develop a strategic research agenda;

- Raise awareness & visibility of the field;

- Make tools for creating & experiencing new media broadly available;

- Empower teachers with 21st Century literacy Skills;

- Work as a community.

(New Media Consortium, 2005, p. 13)

Participatory action research is likely the most productive research and action methodology with which educational departments and organisations may improve the digital literacy in their communities, while at the same time addressing the broader points outlined by the New Media Consortium. Investment in participatory action research projects would offer incentives to communities (including students, parents and citizens) and educational organisations (including teachers, managers and administrators) to work together towards identifying and continually maintaining their collective digital literacy for networked learning.

Wikipedia has a comprehensive, but more importantly, the most participatory source of information about action research - including a quote by Wadsworth (1998) explaining the methodology.

- Participatory Action Research (PAR) is research which involves all relevant parties in actively examining together current action (which they experience as problematic) in order to change and improve it. They do this by critically reflecting on the historical, political, cultural, economic, geographic and other contexts which make sense of it. … Participatory action research is not just research which we hope will be followed by action! It is action which is researched, changed and re-researched, within the research process by participants. Nor is it simply an exotic variant of consultation. Instead, it aims to be active co-research, by and for those to be helped. Nor can it be used by one group of people to get another group of people to do what is thought best for them - whether that is to implement a central policy or an organisational or service change. Instead it tries to be a genuinely democratic or non-coercive process whereby those to be helped, determine the purposes and outcomes of their own inquiry. (Wikipedia, 2005: para. 2, citing Wadsworth, 1998:para. 33)

At first it may appear that participatory action research approaches differ little from typical professional development initiatives. But there are key aspects that are different.

- The explicit aim to engage all stakeholders, especially students, in describing the problems.

- Asking those stakeholders to research the problem and propose solutions.

- Empowering those stakeholders to carry out their plans.

- Repeating the cycle, reflecting on lessons learned and publishing the research.

Remodeling programs like professional development, networking and researching programs into broader scoped, longer termed, community engaged action research projects, may yield interesting results in the area of digital literacy for education. Suggested seed projects might involve a range of areas:

- An Australian/New Zealand version of Levin et al.'s research (2002) Digital Disconnect - The widening gap between Internet savvy students and their schools.

- A look at Doug Brent's (2005) notion of Teaching as performance in the electronic classroom.

- Research into the idea of generation and digital literacy, modeled on Konrad Glogowski's (2005) Digital Pioneers.

- A look at self directed learning in Australia and New Zealand and the capacity for institutional recognition.

Essentially the idea of participatory action in education is not new and has been practiced in the form of Parents & Citizens Associations and Boards of Trustees at most schools, student councils and business and industry relations, and in teacher development. This sort of community involvement would transfer easily into participatory action research. This is a proposal to renew and continue such forms of public participation, focused on the development of digital literacies for enabling open education and networked learning.

Notes

The Action Learning Action Research and Process Management Association (ALARPM Inc.) regularly publishes the Action Learning and Action Research (ALAR) journal. Back issues are available online at: http://www.alarpm.org.au

Australian writers on PAR include Nita Cherry, Karen Malone, Ernie Stringer, Jan Ritchie, Stephen Kemmmis, Richard McTaggart and Ortrun Zuber-Skerrit.

Development of capability edit

Action research was used to develop the capability of tertiary education staff and students in accessing and managing digital information. "They used a wide range of tools, most of which they had never tried before, and which few had confidence in using at the beginning of the project" to create "personal online learning environments" (Hegarty et al., 2010, p. 10). Action learning cycles were an important strategy for supporting the dispositions needed in the digital environment, particularly when using Web 2.0 approaches. A key finding was: " ... the value of having time and permission to ‘play’ within a supportive environment and dynamic learning community" (Hegarty et al., 2010, p. 10).

The dispositions required to obtain an adequate or minimum level of digital information literacy were found to include:

- confidence and belief in own ability (self-efficacy);

- a demonstration of openness;

- the ability to problem solve and take risks;

- technical capability;

- a willingness to collaborate and share; and

- the desire to keep ‘up to date’ driven by the changing contexts of information use and requirements (Hegarty et al., 2010, p. 20).

The outcome of the research is that: " ... there is no one size fits all model. Instead users of digital information are more likely to increase their level of skill and capability if supported to work within an environment which they have created for themselves. ... flexible programmes and strategies were used and they were successful in enabling learners to set their own goals based on personal and professional relevance" (Hegarty et al., 2010, p. 19).

Four main recommendations arose from the research.

1. Learning programmes intended to develop digital information literacy in tertiary education settings must:

- Have personal relevance for individuals and be integrated into everyday, work and study contexts;

- Allow learners the opportunity to ‘play’ and engage in supported exploration, as well as exposing them to new tools and strategies for organising a digital PLE or presence in a networked environment (Web 2.0);

- Recognise the importance of allocating time for regular face-to-face, (or possibly where appropriate, synchronous online) small group, learning opportunities that provide support for diverse self-directed goals and flexible and collaborative approaches to learning;

- Facilitate participation in dynamic learning communities to encourage sharing and collaboration regarding digital information resources and knowledge;

- Encourage meta-cognitive awareness of the learning process, through reflective practice and peer communication;

- Provide support to allow learners to become comfortable with a digital identity and become familiar with ethical behaviour and etiquette in the digital networked environment; and

- Consider the dimensions of digital information literacy, and foster personal capabilities, conducive to success in an ever changing digital environment, as outlined in the definition of DIL developed for the project. (The actual dispositions and skills required are described fully in the project taxonomies, Chapter Three & Appendix 2).

2. Infrastructure at tertiary education institutions should be continually reviewed, in order to capitalise on the benefits of consistent access for staff and students to the latest web technologies, while recognising the ongoing need for security.

3. Educators and information services personnel should continue to engage in discussion and debate with the intention of reviewing and redeveloping a definition of DIL, based on the work done in this project, to underpin future programmes for developing and maintaining the digital information skills and capability of staff and students. (Hegarty, Penman, Kelly, Jeffrey, Coburn & McDonald, 2010.)

Summary edit

It is evident that a social revolution is occurring around the use of Information and Communication Technology. Trends in society are infiltrating the educational sector, and teachers and students are increasingly having to respond to the challenges of the digital environment. It is imperative that all players are supported to develop the necessary capability and dispositions needed for accessing and managing digital information on the Internet, (21st Century literacies) if they are to take part in an open networked and connected society. Participatory action research is mooted as an effective approach for enabling open education and networked learning.

References edit

Australian Capital Territory Department of Education and Training. (2005). Emerging Technologies - a framework for thinking. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.det.act.gov.au/publicat/pdf/emergingtechnologies.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1997). (last updated 18 March 2005, 4228.0) Aspects of Literacy: Assessed Literacy Skills, Austats. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/887AE32D628DC922CA2568A900139365?Open

BECTA. (2005). Open Source Software in Schools - A study of the spectrum of use and related ICT infrastructure costs. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.becta.org.uk/corporate/publications/documents/BEC5606_Full_report18.pdf

Blackall, L. (2005). Early film, early Internet, early days. Teach and Learn Online. Retrieved July 2005 from http://teachandlearnonline.blogspot.com/2005/07/early-film-early-internet-early-days.html

Blackall, L. (2005). Digital literacy: How it affects teaching practices and networked learning futures - a proposal for action research. Knowledge Tree, Edition 7. Retrieved from http://knowledgetree.flexiblelearning.net.au/edition07/html/editorial.html

Boyd, D. (2005). Why Web 2.0 matters: Preparing for glocalization, apophenia: making connections where none previously existed. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2005/09/05/why_web20_matte.html

Brent, D. (2005). Teaching as Performance in the Electronic Classroom. First Monday, 10(4). Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue10_4/brent/

Downes, S. 2005). What eLearning 2 means to you. OLDaily Audio. Transitions in Advanced Learning Conference, Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.downes.ca/files/audio/what_el2_means.mp3

Downes, S. (2004). The Buntine Oration. Stephen's Web. CRLF College of Educators and the Australian Council Educational Leaders conference, Perth, Australia. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/page.cgi?db=post&q=crdate=1097292310&format=full

Farmer, J. (2004). Beyond the LMS. IncSub. Retrieved September 2005 from http://incsub.org/blog/index.php?p=75

Glogowski, K. (2005). Some of us are digital pioneers. Blog of Proximal Development. Retrieved August 2005 from http://www.teachandlearn.ca/blog/2005/08/01/literacy-in-the-digital-age-part-ii/

Hedquist, A. (2008). Ministry says no as school opts for free software. Computerworld NZ. Retrieved August 2008 from http://computerworld.co.nz/news.nsf/tech/CACFF37F34DAE410CC2574E00029A68F

Hegarty, B., Penman, M., Kelly, O., Jeffrey, L., Coburn, D. & McDonald, J. (2010). Digital Information Literacy: Supported Development of Capability in Tertiary Environments. New Zealand: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/tertiary_education/80624

Hotrum, M. (2005). Breaking down the LMS wall. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 6(1). Retrieved March 2005 from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/issue/view/20

Illich, I. (1970). Deschooling Society. Ecotopia. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.ecotopia.com/webpress/deschooling.htm

Jarche, H. (2005). Small (learning) pieces loosely joined. Jarche Consulting. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.jarche.com/node/584

Kamanetz, A. (2010). DIYU: Edupunks, Eduprenuers, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education. Retrieved August 2010 from http://diyubook.com/2010/07/vast-majority-of-professors-are-rather-ludditical/

Levin, D., Arafeh, S., Lenhart, A. & Rainie, L. (2002). The digital disconnect: The widening gap between Internet savvy students and their schools. PEW/Internet American Life Project. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.pewinternet.org/report_display.asp?r=67

Locke, C., Searls, D., Weinberger, D. & Levine, R. (1999). The Cluetrain Manifesto: The End of Business as Usual. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.cluetrain.com/

Linksvayer, M. (2005). 53 Million pages licensed. Creative Commons Weblog. Retrieved September 2005 from http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/5579

Locke, C. & Searls, D. & Weinberger, D. (1999). The Cluetrain Manifesto. Cluetrain website. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.cluetrain.com/

McLuhan, M. (1964). Marshall McLuhan. Wikiquote. Retrieved from http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Marshall_McLuhan

Morrison, D. (2005). elearning frameworks and tools: Is it too late? - The director's cut. Auricle. Retrieved December 2004 from http://www.bath.ac.uk/dacs/cdntl/pMachine/morriblog_more.php?id=315_0_4_0_M

Moyle, K. (2003). Open source software and Australian school education – an introduction. Educationau website. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.educationau.edu.au/papers/open_source.pdf

Moyle, K. (2004). What Place Does Open Source Software Have In Australian And New Zealand Schools and Jurisdictions ICT Portfolios? Total cost of ownership and open source software. Education.au website. Department of Education and Children's Services South Australia. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.educationau.edu.au/research/total_cost_op.pdf

Odlyzko, A. (2001). Content is Not King. First Monday, 6(2). Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue6_2/odlyzko/

OSIA (2004). Northern Territory Department of Education Selects Linux and IBM. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.osia.net.au/open_source_resources/open_source_in_education/use_of_linux_in_schools_in_the_northern_territory

Parkins, G. (2004). e-Learning Adventures Beyond the LMS. Parkin's Lot. Retrieved September 2005 from http://parkinslot.blogspot.com/2004/11/e-learning-adventures-beyond-lms.html

Seimens, G. (2004). Learning Management Systems: the wrong place to start learning. eLearnspace. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/lms.htm

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. eLearnspace. Retrieved June 2005 from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

The Editors. (2010). The Internet as Social Movement. n+1 magazine. Retrieved September 2010 from http://nplusonemag.com/internet-as-social-movement

The New Media Consortium. (2005). A Global Imperative – the report of the 21st century literacy summit. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.newmediacenter.org/pdf/Global_Imperative.pdf

UNESCO Communications and Information Sector – Free Software Portal. (2005). Articles and Reports. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/webworld/portal_freesoft/Information/Articles-Reports/

van Reijswoud, V. & Mulo, E. (2005). OSS for development myth or reality? The case of a university in Uganda. Globale development, East African Center for Open Source. Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda. Retrieved September 2010 from http://www.iicd.org/articles/Article_OSS-UMU.pdf

Wadsworth, Y. (1998). What is Participatory Action Research? Southern Cross University, Graduate School of Management. Retrieved September 2005 from http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/ari/p-ywadsworth98.html

Wikipedia. (2005). Participatory Action Research. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 2005 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Participatory_Action_Research

Wiley, D. (2001). Reusability Paradox, originally written and hosted for the Utah State University. Retrieved September 2005 via the Internet Archive's WayBack Machine from http://web.archive.org/web/20041019162710/http:rclt.usu.edu/whitepapers/paradox.html

A sample of what has been said elsewhere edit

Deschooling Society

By Ivan Illich (1970).

Universal education through schooling is not feasible. It would be no more feasible if it were attempted by means of alternative institutions built on the style of present schools. Neither new attitudes of teachers toward their pupils nor the proliferation of educational hardware or software (in classroom or bedroom), nor finally the attempt to expand the pedagogue's responsibility until it engulfs his pupils' lifetimes will deliver universal education. The current search for new educational funnels must be reversed into the search for their institutional inverse: educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring. We hope to contribute concepts needed by those who conduct such counterfoil research on education—and also to those who seek alternatives to other established service industries.

http://www.ecotopia.com/webpress/deschooling.htm

Something to do, not something to learn: Experiential learning via online role play

By Mary Aquino (2004).

In response to shifts in scientific and psychological thinking coupled with the inescapable impact of technology on cognition and behaviour many contemporary researcher/practitioners are calling for a comprehensive rethinking of teaching and learning methodologies. Prensky (2001) writes largely from personal observation as a designer, trainer and futurist. His work has a distinctly promotional, unacademic tone and his thesis draws on recent and therefore limited research in psychology and neuroscience. However, the essential intuitive accuracy of his observations and the power of his digital native/digital immigrant metaphor have found a receptive audience amongst many teachers and trainers genuinely looking for ways to engage young learners.

http://www.flexiblelearning.net.au/leaders/fl_leaders/fll04/papers/reviewessay_aquino.pdf

Outta My Way Geezer!

By Tom Hoffman (2005).

I am thirty six, and I AM A DIGITAL NATIVE. I know you baby boomers have a hard time coping with this concept because it is a threat to your authority, and as a result you seem to be constantly reinventing the concept so that it can't be applied to any actual adults who can compete with you professionally, but I've had it, and I'm calling bullshit.

http://tuttlesvc.teacherhosting.com/blog/blosxom.cgi/labor/education/405.html

Some of us are Digital Pioneers

By Konrad Glogowski (2005).

Lawrence Lessig says that creativity and innovation always builds on the past. This is exactly what we're doing when we introduce our children to the digital world. Our role as educators, to paraphrase Lessig, is to ensure that the past, the linear, visual mode of thinking give rise to but does not limit the creativity and the energy of emerging technologies. This can happen only if we recognize that we cannot impose the old upon the new just as we cannot create the new in a vacuum. It is our job to ensure that our students acquire the skills necessary to intelligently share their views, whether it's in a wiki, an every-day conversation, or a traditional five-paragraph essay. We need to ensure, as Prensky suggests, that they learn both the legacy and future content. To do that, we need to acquire the skills of digital pioneers, we need to remix and feed forward.

http://www.teachandlearn.ca/blog/2005/08/01/literacy-in-the-digital-age-part-ii/

First Monday Special Issue

Various First Monday writers

Research in the Free/Libre/Open Source (FLOSS) arena is inter-disciplinary and varied. At this point, we already have several years of research in this area with many important intellectual contributions (see http://opensource.mit.edu for a list of papers and active scholars). Many of those contributions have appeared in First Monday and hence, this special issue is a celebration of these contributions and their impact on academia and practice.

http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/special10_10/

Total cost of ownership and open source software

Kathryne Moyle (2004).

As a result of this research then, while information has been gathered that can inform future work undertaken within schools and jurisdictions, it is also apparent that there remains gaps in our knowledge about the extent of use of open source software in schools and the costs associated with its use. Irrespective of any of this however, schools and jurisdictions are choosing to place open source software into their ICT portfolios. Arising from this research then, comes the challenge of how to respond to and manage the emerging use of open source software in schools.

http://www.educationau.edu.au/research/total_cost_op.pdf

Why schools should use exclusively free software

by Richard Stallman (2005).

School should teach students ways of life that will benefit society as a whole. They should promote the use of free software just as they promote recycling. If schools teach students free software, then the students will use free software after they graduate. This will help society as a whole escape from being dominated (and gouged) by megacorporations. Those corporations offer free samples to schools for the same reason tobacco companies distribute free cigarettes: to get children addicted (1). They will not give discounts to these students once they grow up and graduate.

http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/schools.html

Sydney Linux User Group posting

By SLUG member (2002).

We are a school that is into Linux and OSS at the server level and some applications (web based). The issues you have to deal with I believe are not the execs and top level, but the staff, the front-line teachers as it were. They want to use computing tools but they do not want them to get in their way, they need them to assist the education process not hinder. The vast majority of them are familiar with MS Office apps and Windows in general and see no reason to change and what they use at home they want to use at work - no double learning. Of course cost is NOT an issue the vast majority of the software is pirated [at home] and so is essentially free, a kind of Pirate Public License. So you win no friends by even suggesting that there may be another way, they already know that, but don't care.

http://lists.slug.org.au/archives/slug/2002/07/msg00661.html

Use of Linux in Schools in the Northern Territory

By Open Source Industry Australia (2004).

The decision to use Linux and OSS saved the Northern Territory Department of Employment, Education and Training $1M in the first year, and allowed it to put 1000 more workstations into schools.

Open source software and Australian school education

By Kathryn Moyle (2003).

The direct quantitative costs of open source are lower than that of proprietary software. There is debate however, about the qualitative comparative aspects of the indirect costs of open source software when applied within a school environment. No Australian school education research exists that addresses the indirect costs of open source software as they apply to a school environment. In order to gain some common points from which to conduct discussions, research work on this matter would be make a useful contribution to the debate.

http://www.educationau.edu.au/papers/open_source.pdf

What Business can learn from open source

By Paul Graham (2005:para. 1).

Lately companies have been paying more attention to open source. Ten years ago there seemed a real danger Microsoft would extend its monopoly to servers. It seems safe to say now that open source has prevented that. A recent survey found 52% of companies are replacing Windows servers with Linux servers. [1] More significant, I think, is which// 52% they are. At this point, anyone proposing to run Windows on servers should be prepared to explain what they know about servers that Google, Yahoo, and Amazon don't. But the biggest thing business has to learn from open source is not about Linux or Firefox, but about the forces that produced them. Ultimately these will affect a lot more than what software you use.

http://www.paulgraham.com/opensource.html

Open Source Software in Schools - A study of the spectrum of use and related ICT infrastructure costs

By BECTA (2005, p. 3).

Proportionally, support costs accounted for about 60% of the total annual cost per PC in both OSS and non-OSS schools. Annual support costs in individual OSS schools varied widely, but on average were 50–60% of those of their non-OSS counterparts, except OSS secondary schools which had slightly higher costs for informal support. The varying support costs between OSS schools are closely related to the purpose and type of OSS implementation chosen by a school and the purposes for which OSS is being used. The most cost-effective support level and the kind of support required will vary accordingly.

Expenditure on training across all four sets of schools was low. This could partly explain the high support costs; perhaps more or better training could reduce the need for this.

Teachers in the OSS schools view their own skills and confidence in using ICT much more positively than the teachers in the non-OSS schools do, and lower levels of training could therefore be expected.

http://www.becta.org.uk/corporate/publications/documents/BEC5606_Full_report18.pdf

Free and Open Source Software for Development - Myth or Reality? Case study of a University in Uganda

By Victor van Reijswoud and Emmanuel Mulo (2004, p. 9).

For the incoming students a compulsory introductory FOSS computer literacy course was introduced based on a manual (available from www.eacoss.org and the university intranet) developed by the university. This greatly reduced the resistance.

http://www.globaledevelopment.org/Finland%7C14-2-05.pdf

Emerging Technologies - A framework for thinking

By ACT DET (2005).

Positioning the ACT DET to take advantage of emerging technologies will require acknowledgement of the need for cultural change and processes to support and manage it. Students today are ‘native speakers’ of the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet. Many devices described in this report are banned by schools. A shift in culture is crucial to ensure that students’ uses of these devices are embraced as educational opportunities and that they become tools of the trade, rather than be considered contraband.

Many students are entering their school or college with multiple literacies that go beyond text, and this trend will strengthen over the coming years. Educators will need to acknowledge and recognise these new literacies, and build upon and extend them.

The success of such an approach will require that teachers/tutors have access to professional development opportunities to develop confidence in the use of educational technology, as well as informal support environments of peers.

http://www.det.act.gov.au/publicat/pdf/emergingtechnologies.pdf

Conversational writing kicks formal writing's ass

By Kathy Sierra (2005).

If you want people to learn and remember what you write, say it conversationally. This isn't just for short informal blog entries and articles, either. We're talking books. Assuming they're meant for learning, and not reference, books written in a conversational style are more likely to be retained and recalled than a book on the same topics written in a more formal tone. Most of us know this intuitively, but there are some studies to prove it.

http://headrush.typepad.com/creating_passionate_users/2005/09/conversational_.html

Early film, early Internet, early days

By Leigh Blackall (2005).

Costly and unsustainable content development comes from the focus on computers and programs in education throughout the 80's and 90's and a lack of focus on the connectivity and collective learning offered by modem mediated communications. It seems to me that the content creation is very much tied to the process of learning, and that the connectivity offered by the Internet challenges everything about our traditional teacher / student / course / content methods. The content is created by learners as they learn, such as this blog post, what I'm typing and the links I am pointing to.

http://teachandlearnonline.blogspot.com/2005/07/early-film-early-internet-early-days.html

Open Technology Roadmap

By Jamais Cascio (2005).

Openness is at the heart of truly world changing systems. Transparency of process, connections and results make open systems more reliable, more accessible, and better able to be connected to other systems; it also encourages collaboration and the input of interested stakeholders. This is perhaps most tangible in the world of technology, particularly information and communication technology (ICT); open ICT systems are increasingly engines of innovation, and are clear catalysts for leapfrogging across the developing world, via reduced costs, potential for customization, and likely interoperability with both legacy and emerging technologies.

http://www.worldchanging.com/archives/003485.html

Summarising A Roadmap for ICT EcoSystems

By Harold Jarche (2004).

The Problem = 'In the race to identify victims and assist survivors, Thailand's government hits its own wall. Responding agencies and non-governmental groups are unable to share information vital to the rescue effort. Each uses different data and document formats. Relief is slowed; coordination is complicated. The need for common, open standards for disaster management was never more stark or compelling. The Royal Government of Thailand responded by creating a common website for registering missing persons and making open file formats in particular an immediate national priority.'

The Solution = Open Standards

http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/epolicy/roadmap.pdf

From Andragogy to Heutagogy

By Stewart Hase and Chris Kenyon (2000).

Our educational systems have traditionally been based on Lockean assumptions ... In this paradigm learning has to be organised by others who make the appropriate associations and generalisations on behalf of the learner. Thus, random individual experiences are taken to be totally inadequate as sources of knowledge, the educational process needs disciplined students, and literacy is seen to precede knowledge acquisition. Success is based on attending to narrow stimuli presented by a teacher, an ability to remember that which is not understood, and repeated rehearsal (Emery, 1974, p. 2).

An alternate view is proposed by Heider and assumes that people can make sense of the world and generalise from their particular perceptions, can conceptualise, and can perceive invariance (Emery, 1974). Thus, people have the potential to learn continuously and in real time by interacting with their environment, they learn through their lifespan, can be lead to ideas rather than be force fed the wisdom of others, and thereby they enhance their creativity, and re-learn how to learn.

http://ultibase.rmit.edu.au/Articles/dec00/hase2.htm

A Global Imperative: Report of the 21st Century Literacy A Global Imperative

By The New Media Consortium (2004).

21st century literacy is the set of abilities and skills where aural, visual and digital literacy overlap. These include the ability to understand the power of images and sounds, to recognize and use that power, to manipulate and transform digital media, to distribute them pervasively, and to easily adapt them to new forms. (p2)

The strategic priorities for creating change (p. 13):

- Develop a Strategic Research Agenda

- Raise Awareness & Visibility of the Field

- Make Tools for Creating & Experiencing New Media Broadly Available

- Empower Teachers with 21st Century Literacy Skills

- Work as a Community

http://www.newmediacenter.org/pdf/Global_Imperative.pdf

Why Web 2.0 Matters: Preparing for Glocalization

By Danah Boyd (2005).

Glocalized structures and networks are the backbone of Web2.0. Rather than conceptualizing the world in geographical terms, it is now necessary to use a networked model, to understand the interrelations between people and culture, to think about localizing in terms of social structures not in terms of location. This is bloody tricky because the networks do not have clear boundaries or clusters; the complexity of society just went up an order of magnitude.

http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2005/09/05/why_web20_matte.html

Small (Learning) Pieces Loosely Joined

By Harold Jarche (2006).

This is still a difficult message to get past many educational institutions and training organisations. You don't have to spend a lot on the technology. You need to focus on getting the people and processes aligned so that learning happens. Save the money that you would spend on an LCMS and put it into the time to let people develop processes that work for their unique contexts.

http://www.jarche.com/2006/09/small-schools-loosely-joined/

Literacy

By the Wikipedia community (2009).

For the contemporary world literacy now comes to mean more than just the ability to read, write and be numerate. It involves, at all levels, the ability to use and communicate in a diverse range of technologies. Since the computer became mainstream in the early 1990s, its importance and centrality in communication has become unassailable.

We should now, properly, speak of "literacies". These literacies always involve technology and the ability to use technology to negotiate the myriad of discourses that face us in the modern world. These literacies concern using information skillfully and appropriately, and are multi-faceted and involve a range of technologies and media.

In sum, today's students need to cope with a complex mix of visual, oral, and interactive media as well as traditional text. People of lesser education or older people may see themselves falling behind as the informational gap between them and the people literate in the new media and technologies widens.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literacy

Literacy in the Information Age: Final Report of the International Adult Literacy Survey

By OECD (2000).

Low literacy skills are evident among all adult groups in significant - albeit varying - proportions. Literacy proficiency varies considerably according to home background factors and educational attainment in most of the countries surveyed. However, the relationship between literacy skills and educational attainment is complex. Many adults have managed to attain high levels of literacy proficiency despite a low level of education; conversely, some have low literacy skills despite a high level of education. These differences matter both economically and socially: literacy affects, inter alia, labour quality and flexibility, employment, training opportunities, income from work and wider participation in civic society. Improving the literacy skills of the population remains a large challenge for policy makers. The results suggest that high-quality foundation learning in schools is important but insufficient as a sole means to that end. Policies directed at the workplace and family settings are also needed. The employers’ role in promoting and rewarding literacy skills is particularly important for skills development.

http://www1.oecd.org/publications/e-book/8100051e.pdf

Aspects of Literacy: Assessed Literacy Skills

By Australian Bureau of Statistics (2005).

The SAL did not define literacy in terms of a basic threshold, above which someone is 'literate' and below which someone is 'illiterate'. Rather it defined literacy as a continuum for each of the three types of literacy (consistent with international practice, these are also referred to as the prose, document and quantitative scales) denoting how well people used material printed in English. Progression along this continuum was characterised by increased ability to 'process' information (for example to locate, integrate, match and generate information) and to draw correct inferences based on the information being used.

http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/887AE32D628DC922CA2568A900139365?Open

Internet Activity, Australia 2005

By Australian Bureau of Statistics (2005).

At the end of March 2005, total Internet subscribers in Australia numbered 5.98 million. While this was an increase of 239,000 (4%) from the end of September 2004, growth had slowed following a 10% increase recorded for the six months to the end of September 2004.

http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookupMF/6445F12663006B83CA256A150079564D

Breaking the LMS wall

By Michael Hotrum (2005).

“All in all it was just a brick in the wall. All in all it was all just bricks in the wall.” (Pink Floyd, November 30, 1979) The Internet is independent of device (hardware or platform), distance, and time, and is well-suited for open, flexible, and distributed learning. Yet traditional online, distributed learning methods are anything but flexible, open, or dynamic. What went wrong? Parkin (2004a, b) believes that we failed to appreciate that the Internet is a vehicle for connecting people with each other. We implemented LMS methods that imposed bureaucratic control, diminished learner empowerment, and delivered static information. “In a world hurtling toward distributed internetworking, e-learning was still based on a library-like central-repository concept.” Parkin suggests it is time to explore the true promise of e-learning, and to rework our ideas about how learning should be designed, delivered, and received. It is time to stop letting the LMS vendors tell us how to design learning. It is time to stop the tail from wagging the dog.

http://www.irrodl.org/content/v6.1/technote44.html

The Cluetrain Manifesto

By Chris Locke, Don Searls and David Weinbergner (1999).

Corporate firewalls have kept smart employees in and smart markets out. It's going to cause real pain to tear those walls down. But the result will be a new kind of conversation. And it will be the most exciting conversation business has ever engaged in.

Networked markets are beginning to self-organize faster than the companies that have traditionally served them. Thanks to the web, markets are becoming better informed, smarter, and more demanding of qualities missing from most business organizations.

Teaching as performance in the electronic classroom

By Doug Brent (2005).

One of the most useful concepts for understanding modern life is "residual orality." Ong pointed out that before the printing press stabilized the effects of literacy, many aspects of society remained oral. Manuscripts were often read aloud, even by people reading them in private. Oral debates were a major way of producing knowledge. Witnesses were more important than documents. Now the printing press has made residual orality a much smaller part of everyday life. However, in many areas of life, oral performance has been remarkably resistant to being "textualized": that is, taken over by written or electronic texts. Teaching is one of these areas.

I want only to use this phenomenal persistence of the performative, after 500 years of technologies that could in principle have replaced it with textualization, as a reason to reflect carefully on what now seems to be happening to notions of intellectual property as online technologies promise increasing textualization of teaching.

http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue10_4/brent/

Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age

By George Siemens (2004).

Connectivism is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and complexity and self-organization theories. Learning is a process that occurs within nebulous environments of shifting core elements – not entirely under the control of the individual. Learning (defined as actionable knowledge) can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database), is focused on connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing.

Connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital. The ability to recognize when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.

http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

Most scientific papers are probably wrong

By Kurt Kleiner for New Scientist (2005).

Most published scientific research papers are wrong, according to a new analysis. Assuming that the new paper is itself correct, problems with experimental and statistical methods mean that there is less than a 50% chance that the results of any randomly chosen scientific paper are true.

Comment by George Siemens: What I find interesting is not that the papers themselves are wrong, but that there are very limited opportunities for readers to correct and discuss the paper in its original context. Any format that is "set in stone" isn't going to work today. Blogs are particularly effective at enabling the inclusion of contrary viewpoints. Journals are still one-way, broadcast tools. Perhaps journal publishers should reflect on what's happening to TV, newspapers, and music. Two-way knowledge flow is critical.

http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn7915&feedId=online-news_rss20

New publishing paradigms and the 'free for education' license

By Phillip Crisp

Briefly examining the historical evolution of publishing models from relatively proprietary to the new paradigm described as ‘open source / open content’. Explaining those fundamental structures and concepts underlying AEShareNet which are helpful in understanding the AEShareNet-FfE licence protocol.

http://www.bakercyberlawcentre.org/unlocking-ip/s4_speakers.html

Free/Open source software in education

By Tan Wooi Tong (2004).

FOSS [Free and Open Source Software] can lower the barriers to the access of ICTs by reducing the cost of software. The initial acquisition cost of FOSS is negligible. Indeed, it is usually possible to download FOSS without any cost. If there is limited bandwidth, it may be more convenient to get the software in a CD-ROM for a nominal fee. But there is no licensing fee for each user or computer and it can be freely distributed once a copy is downloaded or made available on a CD-ROM. Hence, the initial cost of acquiring FOSS is much lower than the cost of acquiring proprietary software for which license fees have to be paid for each user or computer. Upgrades of FOSS can usually be obtained in a similar way, making the upgrade costs negligible as well. In contrast, proprietary software upgrades normally have to be paid for even though the upgrade costs may be lower than the initial cost.

http://www.iosn.net/education/foss-education-primer/fossPrimer-Education.pdf

Using free and open source software to create free and open courseware

By Leigh Blackall (2004).

The freedom to acquire and use a range of free and open source software whenever and wherever I need them gives me a great deal of flexibility and increased professional capacity. In particular, I can work nomadically, which is to say, like our students, on many different computers, at home or at work, not restricted to one single computer and operating system, and not limited to the version of software being used.

http://www.flexiblelearning.net.au/community/TechnologiesforLearning/content/article_6885.htm

The Buntine Oration: Learning Networks

By Stephen Downes (2004). Delivered to the Australian College of Educators and the Australian Council of Educational Leaders conference in Perth, Australia.

While I was thinking of what the educational system could become, the network of publishers and software developers and educational institutions that developed around the concept of learning objects had a very different idea.

Here's what it would be. Learning resources would be authored by instructors or (more likely) publishing companies, organized using sequencing or learning design, assigned digital rights and licenses, packaged, compressed, encrypted and stored in an institutional repository. They would be searched for, located, and retrieved through something called a federated search system, retrieved, and stored locally in something called a learning content management system. When needed, they would then be unpacked and displayed to the student, a student who, using a learning management system, would follow the directions set out by the learning designer, work his or her way through the material, maybe do a quiz, maybe participate in a course-based online discussion.

That's the picture. That's the brave new world of online learning. And honestly, it seems to me that at every point where they could have got it wrong, they did.

http://www.downes.ca/cgi-bin/page.cgi?db=post&q=crdate=1097292310&format=full

The Reusability Paradox

By The Reusability, Collaboration, and Learning Troupe at Utah State University (2001).

The method learning object proponents have evangelized as facilitating reusability of instructional resources may in fact make them more expensive to use than traditional resources. We have demonstrated that the automated combination of certain types of learning objects can in fact be automated. However, it would appear that the least desirable relationship possible exists between the potential for learning object reuse and the ease with which that reuse can be automated: the more reusable a learning object is, the harder its use is to automate. Identically, the less reusable a learning object is, the easier its use is to automate. This discovery is depressing, indeed.

http://web.archive.org/web/20041019162710/http://rclt.usu.edu/whitepapers/paradox.html

Content is not king

By Andrew Odlyzko (2001).

"What would the Internet be without "content?" It would be a valueless collection of silent machines with gray screens. It would be the electronic equivalent of a marine desert - lovely elements, nice colors, no life. It would be nothing". [Bronfman]

The author of this claim is facing the possible collapse of his business model. Therefore, it is natural for him to believe this claim, and to demand (in the rest of the speech [Bronfman]) that the Internet be designed to allow content producers to continue their current mode of operation. However, while one can admire the poetic language of this claim, all the evidence of this paper shows the claim itself is wrong. Content has never been king, it is not king now, and is unlikely to ever be king. The Internet has done quite well without content, and can continue to flourish without it. Content will have a place on the Internet, possibly a substantial place. However, its place will likely be subordinate to that of business and personal communication.

http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue6_2/odlyzko/

The Digital Disconnect: The widening gap between Internet-savvy students and their schools

By Doug Levin, Sousan Arafeh, Amanda Lenhart & Lee Rainie (2002).

Many schools and teachers have not yet recognized—much less responded to—the new ways students communicate and access information over the Internet. Students report that there is a substantial disconnect between how they use the Internet for school and how they use the Internet during the school day and under teacher direction. For the most part, students’ educational use of the Internet occurs outside of the school day, outside of the school building, outside the direction of their teachers.

http://www.bakercyberlawcentre.org/unlocking-ip2004/s4_speakers.html