Exercise as it relates to Disease/Exercise training effect on Obstructive Sleep Apnea and sleep quality

This is an analysis of the journal article “The Effect of Exercise Training on Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Sleep Quality: A Randomized Controlled Trial” by Christopher E. Kline et al. (2011).[1]

What is the background to this research? edit

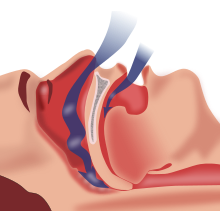

According to the Sleep Health Foundation, Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) refers to those patients who suffer from repeated episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the throat during sleep.[2] The symptoms including snoring, tossing and turning, and waking during the night – sometimes gasping or choking for air.[2] It is estimated that approximately 9% of Australian women and 25% of Australian men have clinically significant OSA, and 4% have symptomatic OSA.[3]

Key terms: edit

- Apnea = complete cessation of air flow for at least 10 seconds.[4]

- Hypopnea = reduction in airflow that is followed by an arousal from sleep or a decrease in oxyhemoglobin saturation.[4]

- Apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) = number of apneas per hypopnea per hour of sleep.[4]

- Polysomnogram (PSG) = gold standard of diagnostic OSA testing – involves simultaneous recordings of multiple physiologic signals during sleep that allow identification of sleep-related apneas and hypopneas.[4]

- Actigraphy = non-invasive method of monitoring activity and rest cycles - via a sensor that is worn (usually on the wrist), for a week or more to measure gross motor activity.[5]

- N3 sleep = known as Delta Sleep, or slow wave sleep, is a regenerative period of sleep that lasts between 45-90min.[6]

Where is the research from? edit

Authors: Christopher E. Kline, PhD, E. Patrick Crowley, MS, Gary B. Ewing, MD, James B. Burch, PhD, Steven N. Blair, PED, J. Larry Durstine, PhD, J. Mark Davis, PhD, Shawn D. Youngstedt, PhD.

- Christopher E. Kline is especially well researched in the field of sleep testing in different populations, yielding more than 25 similar studies and publications related to sleep.[7]

The trial was conducted in Dr. Youngstedt's Chronobiology Laboratory, as well as the Clinical Exercise Research Center at the University of South Carolina, and the WJB Dorn VA Medical Center Sleep Laboratory. It was funded by a Public Health Dissertation Grant from the Centre for Disease Control Prevention (CDC); however they note that the results do not necessarily reflect the views of the CDC.

What kind of research was this? edit

This is a randomised controlled trial (RCT), of 43 sedentary and overweight/obese individuals aged 18-55 with at least moderate-severity untreated OSA. RCT's are considered the gold standard of testing due to the following factors:

What did the research involve? edit

Participants were randomly divided into two groups – an exercise training group and a stretching control group, both for the duration of 12 weeks. The exercise training group met four times per week to perform 150 min per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, as well as meeting to perform resistance training twice per week. The stretching control group met twice per week to perform low-intensity exercises aimed at increasing whole-body flexibility. The use of a laboratory PSG for one night pre- and post-intervention was used to assess OSA severity and quality of sleep, as well as actigraphy (7-10 days), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Participant lifestyle and eating habits were also monitored.

What were the basic results? edit

Kline C. E. et al.[1] found in their results that exercise helped to reduce some of the symptoms of OSA. The exercise training group saw a decrease in AHI ≥ 15 – 32.3 ± 5.6 to 24.6 ± 4.4, whilst the stretching group saw an increase in AHI – 24.4 ± 5.6 to 28.9 ± 6.4. Both groups saw changes in oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and stage N3 sleep, again showing that the stretching group's symptoms regressed further whilst the exercise group's symptoms improved in all categories displayed in the table below.

| Variable | Exercise Baseline | Exercise Post | Stretching Baseline | Stretching Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea Index | 21.7 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 20.9 |

| Hypopnea Index | 10.5 | 9.6 | 9.3 | 8.0 |

| ODI | 24.5 | 21.5 | 16.8 | 23.2 |

| Stage N3 Sleep | 12.8 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 9.2 |

Individuals in the exercise group also reported improvements in actigraphy sleep and sleep quality, as well as feeling generally more satisfied with their treatment allocation compared to the stretching group. Correspondingly, the researchers found that those who finished the intervention in the stretching group had a lower rate of attendance than those in the exercise training group (86.7% vs. 93.1%), which may have had an effect on the results obtained. The researchers also note the two major limitations of the study to be the pre- and post- intervention PSG performed, as it may have presented additional variability in measures of OSA severity, and the lack of snoring measurement.

What conclusions can we take from this research? edit

This research suggests that exercise could be an effective treatment for reducing OSA symptoms. There have been numerous relevant studies conducted since 2011 that have yielded similar results and support this statement.[9][10] It is also important to note that there have been studies that look at the roles inversely – the effect that sleep apnea has on one’s ability to exercise, and to take into account that those who suffer from OSA may be afflicted with an impaired capacity to exercise and therefore may develop potentially adverse responses to exercise.[11][12]

Practical advice edit

This research supports exercise as a beneficial treatment method for OSA. However it is important to note that as the typical demographic of those with OSA are overweight/obese, they may also likely suffer from cardio-respiratory risks or diseases, and should therefore complete exercise pre-screening prior to beginning an exercise intervention. Support from a general practitioner and an informed exercise trainer would assist with correct exercise prescription and injury prevention.

Further information/resources edit

For further information regarding Obstructive Sleep Apnea, please click on the links below:

- OSA facts: http://www.snoreaustralia.com.au/obstructive-sleep-apnoea.php

- OSA treatment options: http://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/fact-sheets-a-z/465-treatment-options-for-obstructive-sleep-apnea-osa.html

- Further evidence to support exercise as OSA treatment: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joseph_Norman2/publication/11955895_Exercise_training_effect_on_obstructive_sleep_apnea_syndrome/links/560842b408ae8e08c09460ca.pdf

References edit

- ↑ a b 1. Kline, C. E. et al. (2011). The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep, 34(12), 1631-1640.

- ↑ a b 2. Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). (2017). Sleephealthfoundation.org.au. Available from http://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/fact-sheets-a-z/191-obstructive-sleep-aponea.html

- ↑ 3. Obstructive sleep apnoea. (2017). Snoreaustralia.com.au. Available from http://www.snoreaustralia.com.au/obstructive-sleep-apnoea.php.

- ↑ a b c d 4.Punjabi, N. M. (2008). The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 5(2), 136-143.

- ↑ 5. Pollak, C. P., Tryon, W. W., Nagaraja, H., & Dzwonczyk, R. (2001). How accurately does wrist actigraphy identify the states of sleep and wakefulness?. Sleep, 24(8), 957-965.

- ↑ 6.Nasca, T., & Goldberg, R. (2017). The Importance of Sleep and Understanding Sleep Stages - SleepHealth. SleepHealth. Available from https://www.sleephealth.org/sleep-health/importance-of-sleep-understanding-sleep-stages/

- ↑ 7. Available via searching: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?start=6&q=%22author:Kline+author:C.%22+sleep&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5

- ↑ a b c Stang, A. (2011). Randomized controlled trials—an indispensible (sic) part of clinical research. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(39), 661.

- ↑ Kline, C. E., Ewing, G. B., Burch, J. B., Blair, S. N., Durstine, J. L., Davis, J. M., & Youngstedt, S. D. (2012). Exercise training improves selected aspects of daytime functioning in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 8(4), 357.

- ↑ 9. Iftikhar, I. H., Kline, C. E., & Youngstedt, S. D. (2014). Effects of exercise training on sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Lung, 192(1), 175-184.

- ↑ 10. Evans, C. A., Selvadurai, H., Baur, L. A., & Waters, K. A. (2014). Effects of obstructive sleep apnea and obesity on exercise function in children. Sleep, 37(6), 1103-1110.

- ↑ Beitler, J. R., Awad, K. M., Bakker, J. P., Edwards, B. A., DeYoung, P., Djonlagic, I., ... & Malhotra, A. (2014). Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with impaired exercise capacity: a cross-sectional study. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10(11), 1199.